Ever since 20 July 1969, the Apollo 11 spacecraft landed successfully with its crew on the lunar mare called the Sea of Tranquility, humanity has been obsessed with space. While concentrating on smaller projects, in the previous decades, Europe silently supported the space sector, staying in the background. However, with the revival of the space race, the European Space Agency switched into higher gear.

From the moment Neil Armstrong took his historic steps, we’ve been waiting for something that would trump landing on the moon. The wait has been longer than expected: since 12 December 1972—the last mission to the Moon—no man has set foot on either the moon or on any other planet. After the growing success of the private sector and the emergence of China on the scene, NASA fired up the rockets once again. In recent years, these two have been outbidding each other with ambitious goals. China aims to build a permanent, self-sustaining lunar base by 2028, while the US wants to land on the Moon by 2025 and send astronauts to Mars sometime between 2030 and 2040. Of course, Elon Musk can’t be left out of the list of ambitious space players either, as SpaceX is planning to launch Starship, the world's biggest rocket ever, in March 2023.

Where has Europe been in the meantime?

In the 1940s, a number of excellent scientists left Europe to pursue their research either in the Soviet Union or in the United States. Smaller countries soon realised that their space projects cannot compete with those of the superpowers. After the Sputnik crisis of 1958 when, to everyone's surprise, the Soviet Union launched the world's first working satellite, the first negotiations got underway. Eventually, in 1962, the Western European countries founded the European Space Research Organisation (ESRO), the predecessor of today's European Space Agency (ESA).

In its current form, ESA was established in 1975 by ten countries. Ministerial Commissioner for Space Research, Orsolya Ferencz also points out that Europe has had to overcome a major competitive disadvantage:

‘In the last century, the countries of the European Union were mankind’s centres of innovation, but recently the situation has changed. The European community has fallen behind in the space sector. One significant example is the fact that in order to get a man on a satellite or onto a space station, one must turn to the US, Russia or China, as currently these three countries have spacecrafts.’

From our region, Austria was the first to join the ESA in 1986, followed by Czechia in 2008, Romania in 2011, Poland in 2012 and Estonia and Hungary in 2015. Even within the CEE region, countries invest in space policy to a varying degree and not everyone is involved in the joint European efforts the same way either. ‘While we’ve been paying less attention to the space sector, in the last decade, Poland and Czechia have spent huge amounts of money on it’—the Ministerial Commissioner pointed out.

To infinity and beyond

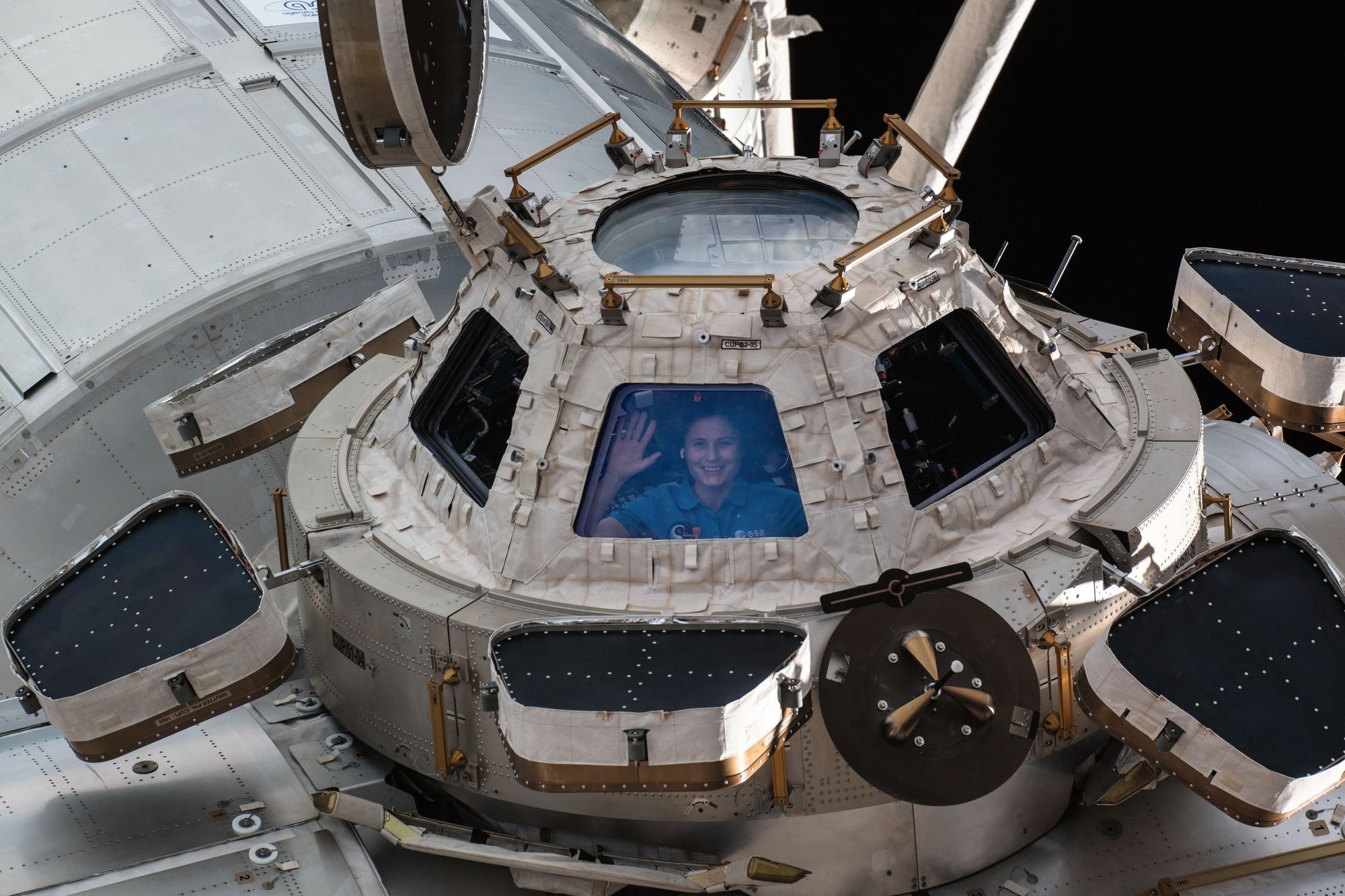

The first ESA astronaut to leave Earth was Ulf Merbold from Germany in 1983. Currently, seven active astronauts work for the Agency, who were recently joined by seventeen new recruits selected for training at the European Astronaut Centre in Cologne. Countries are also selecting and training future astronauts as part of their national space programmes. For example, Hungary is spending around $100 million on the HUNOR (Hungarian Orbit) project to send a Hungarian astronaut to space in 2024-25, after Bertalan Farkas in 1980.

‘Submitted by professionals from various fields, the jury of experts accepted 247 applications, written by lawyers, archaeologists, doctors, pilots and others. Physical fitness, psychological, mental stability and resilience are all equally important, as well as being professionally competent. The training process is extremely complex and difficult. As project astronauts, they won’t be piloting the spacecraft, but they still need to be familiar with how the space station operates’—State Commissioner Orsolya Ferencz explained.

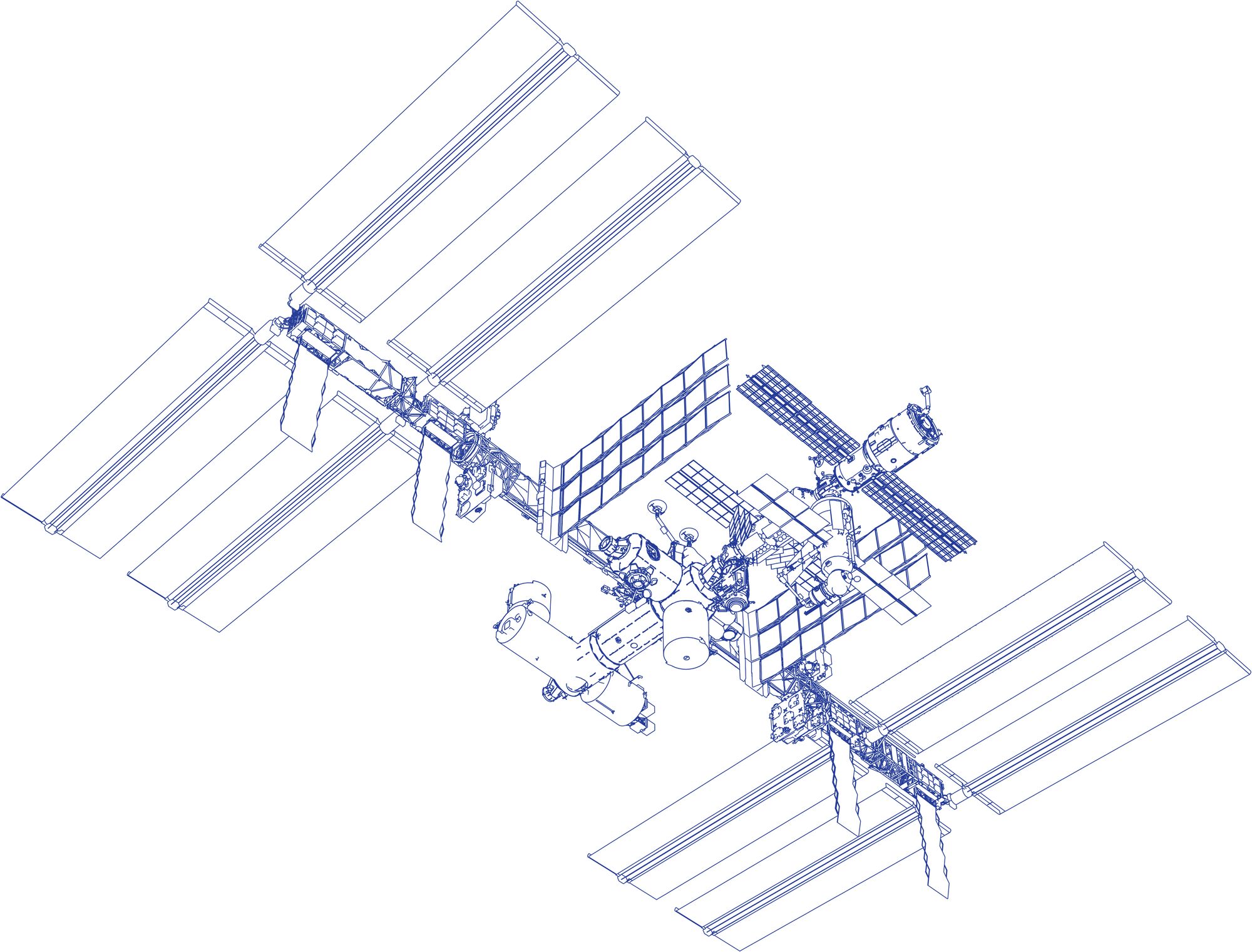

The organisation has six major centres, one of which is located off the continent, in French Guiana, from where the launchers are fired. The launch site was built there because Guiana is close to the Equator, and due to the rotation of the Earth, the Equator has the highest peripheral velocity, meaning that if a rocket is launched in the right direction, less fuel is needed for take-off. While it is clear that the European Space Agency can’t compete with either the US or China in terms of spectacular projects, it has plenty to be proud of, even without sending someone to Mars...

Illustration: László Bárdos

Photos: ©ESA/NASA – T. PESQUET, ©NASA, ESA, CSA, AND STSCI, ©ESA/NASA

Continue reading in H&H issue no.7!

ORDER HERE

The pantheon of Hungarian animation | TOP 5

Strawberry inspired Oana Stănescu’s captivating installation