In this article, we talked to Géza Szöllősi, known to many as the art director of the 2006 Hungarian film Taxidermia, but his art is much more diverse than that. Immerse yourself in the world of the Budapest horror!

Essentially, you studied graphic design. How did you come to make art from organic materials?

As a child in the suburbs of Budapest in the eighties, visual arts seemed to be a pastime, and pop culture products were slowly infiltrating from the West in the form of films and newspapers. A few magazines, including IPM (Interpress Magazine), regularly published quality illustrations in their genre, such as the work of the justly acclaimed Boris Valleyo. So I thought that if I wanted to produce such beautiful pictures myself, I should become a graphic designer, which is why I chose the University of Art and Design (now MOME). At the time, there was a considerable over-application, as there was no other higher education in this field apart from this and the University of Fine Arts. The numerous failed entrance exams didn’t discourage me either, and for fun, I took a window dressing course, which at the time was a state-funded preparatory course for those dismissed for the reasons mentioned above. In addition, I spent two years in Pécs studying painting, which was a major turning point in my view of the world, because it was there that I first experienced children painting or sculpting for no particular reason. Eventually, I was accepted to study graphic design at the University of Art and Design. By then I had developed a passion for making objects and pictures just for my own amusement.

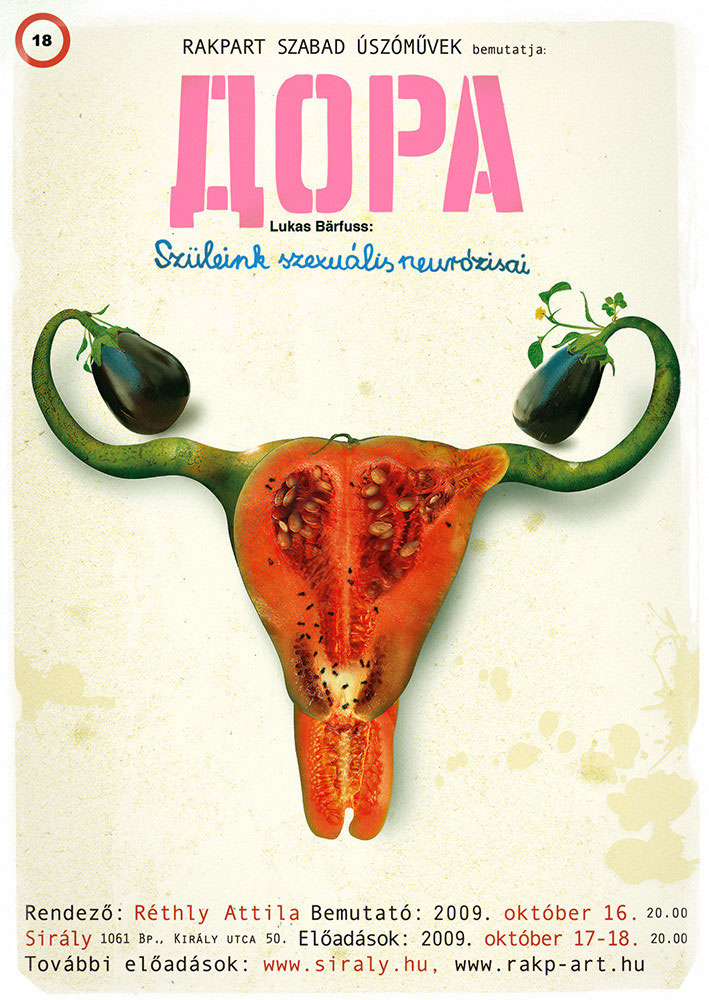

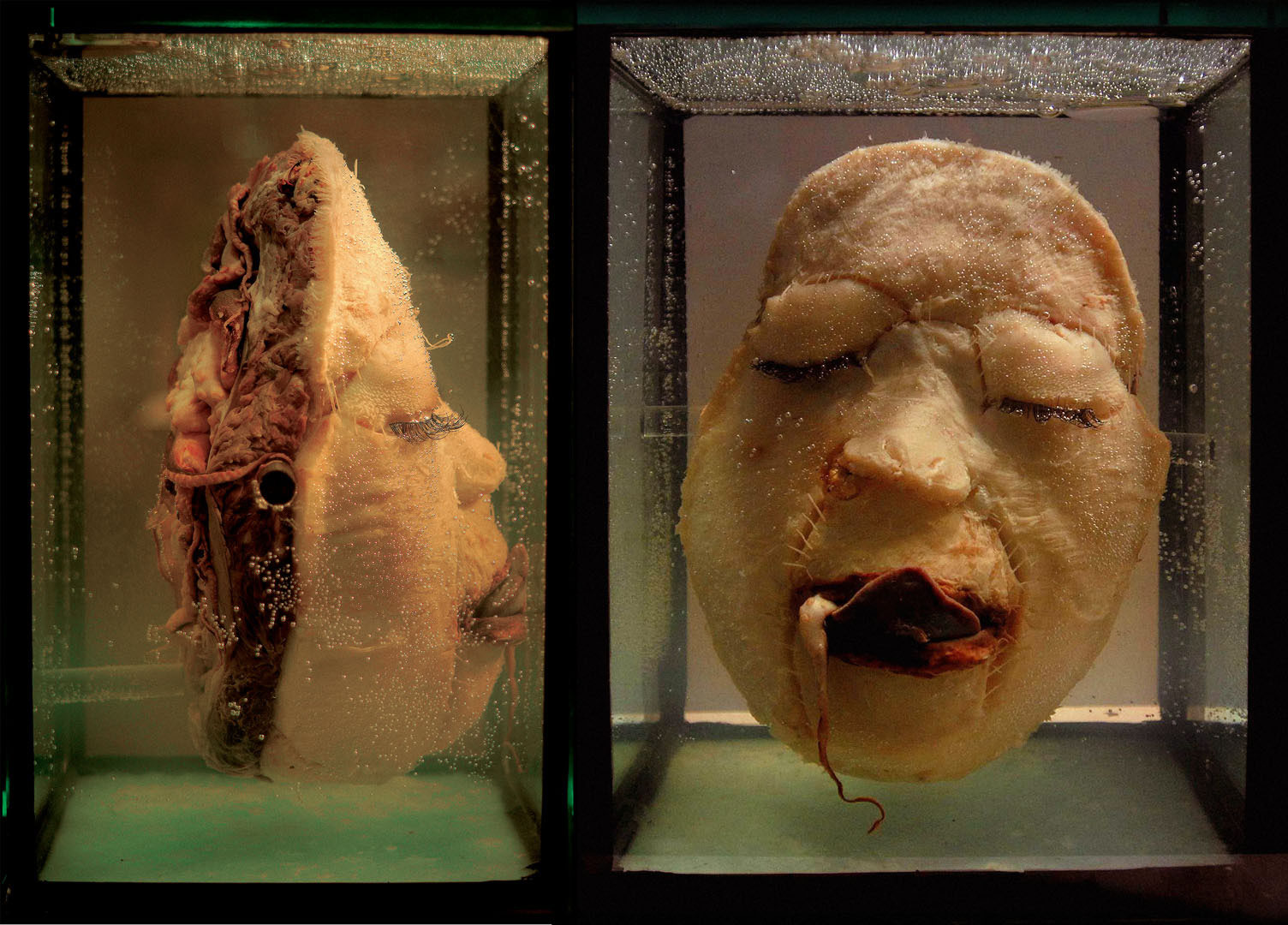

Nowadays, in addition to visual art, I spend my time with graphic design and many forms of visual design. It’s a rather awkward situation, as I’m considered an applied graphic designer in the film and theater industry, I’m seen as a mental visual artist among graphic designers, while my visual artist friends refer to me as a kind of visual designer. The taxidermy and the flesh... well, yes. Back in university, there was a photography course where you had to make a portrait of yourself without being present in the picture. That’s when I had the idea of making my portrait out of pork. This later grew into Project Flesh.

You’ve mentioned elsewhere that people thought what you did was weird since elementary school. Tell us about that.

Strange is the opposite of boring. It’s hard for the younger generation to understand the hunger for images that we had to endure in the eighties—that’s how we became omnivores. It was the heyday of VHS, we watched all the trash movies as kids, horror and sci-fi alike. Maybe because I was exposed to these influences at a very receptive age, their aesthetics became the standard for me. If I had been taken to the Kunsthalle as a child, I might have been fond of abstract art. But that’s all in the past now, because the mainstream media has had plenty of time for the kind of decadent art we’re talking about here. To name just the most common and currently most popular: Last of Us, Stranger Things. Nowadays, an exhibition such as Decadence Now! in Prague would not receive universal acclaim from the profession or the general public, even though it featured artists who have long been classics in the Western world.

It’s interesting that you say that because I’ve noticed that most people find your work difficult to absorb.

Well, I don’t know if I should laugh or cry. In fact, it’s a kind of hypocrisy, because people who used to binge watch the TV show CSI, for example, didn’t realize that they were actually consuming necrophiliac erotica. In each episode, a particularly beautiful female or male corpse was presented for dissection, and the camera lingered on the slashed bodies for a long time. These viewers are perverts.

I’ve read in several articles that you don’t like your work to be portrayed as horrible, because you don’t aim to scare. Then what would you say your goal is?

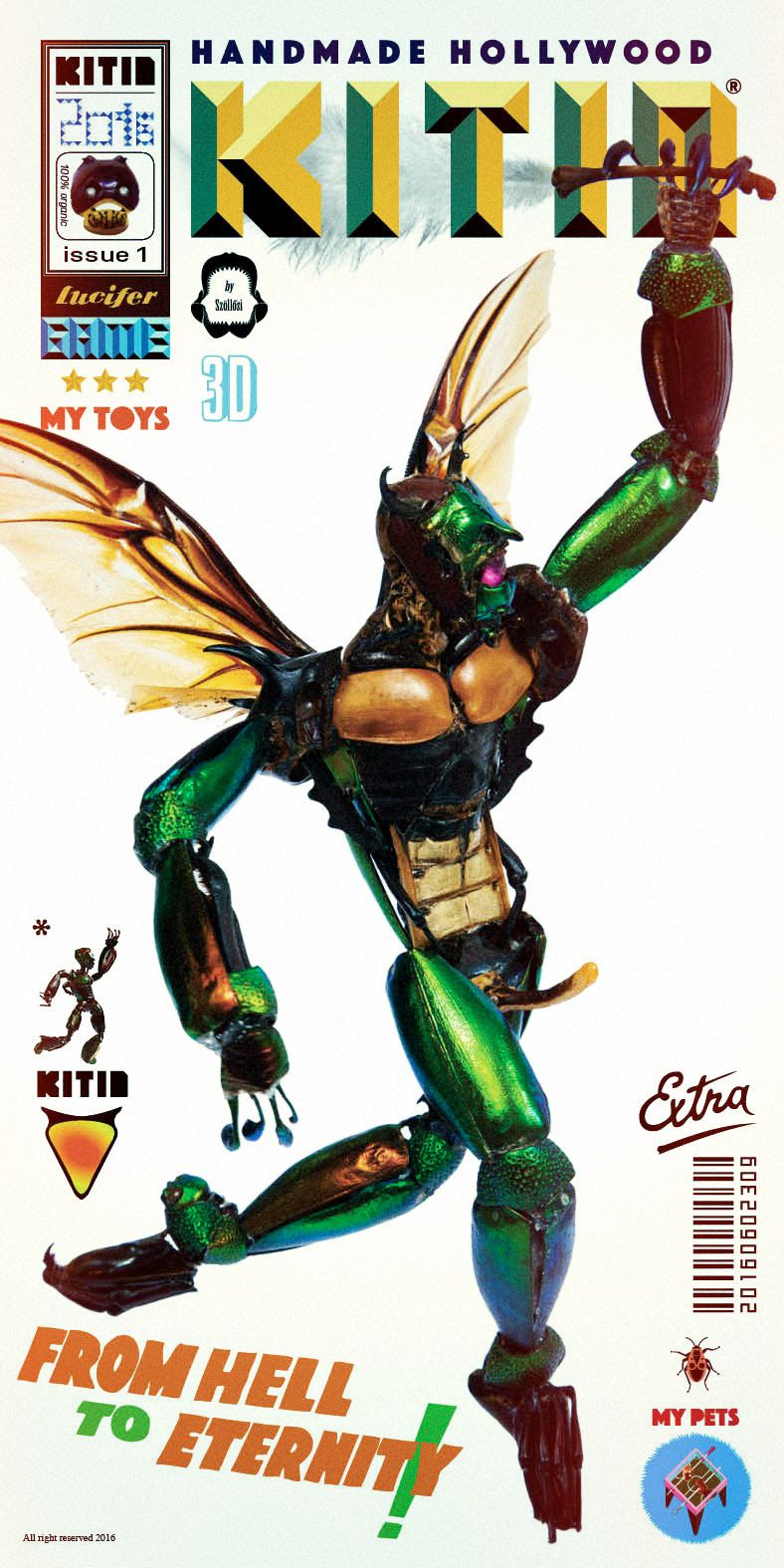

A self-exciting process of creation is when you can do something, you do it. So the final visual is maximized to the extent possible. Perhaps the only thing missing from my work is the Hollywood glamour filter compared to what I’ve just said. In any case, I think the best word to describe most of my projects is divisive. The animal fur in the My Pets series is what blows the fuse, and the Kitin Project fans the flames with the arthropod legs of cute bugs.

You used to say you didn’t have any serious connection to meat, it was just a good ingredient. Have you developed some kind of thought or philosophical framework over time?

It is a nineteenth-century romantic approach to think of the artist wandering the streets at night, getting the wind in their oversized scarf, and then returning to their humble attic room and immediately pouring their heart out in the form of a painting. It is a profession like any other. In the vast majority of the cases, the content of a writer or a director’s work is not related to their personality, however aberrant they may be. Moreover, the same is true of actors, for just as Isaura is not a slave, Anthony Hopkins is not a cannibal.

So in that sense, I don’t have any particular personal connection with meat, I just think it’s an excellent raw material for expressing my ideas and concepts and making an impact. In the twentieth century, the possibility has opened up to include other inferior materials in high art, in addition to the ‘noble materials’. Both meat and animal fur, as well as chitinous armor, have the fantastic property of infinite resolution and detail. They can therefore be perfect components of montages. My works could be called in many ways, but they are still montages.

I am also currently writing my dissertation on the nature of montage at the University of Pécs, Faculty of Music and Visual Arts DLA School. A common element in my sculptures is taking things apart and then putting them back together in a completely different way. This is where a helpful friend in the form of organic materials comes in handy.

Most of the time, I find the right material by chance, and the way the material influences the final message of the works is equally unpredictable. When I first started experimenting with flesh—for the portrait assignment at university—I didn’t realize that it wouldn’t actually be a portrait of a living person, but of a dead one. In every project where I work with organic materials, I deal with death in some way or another. Living material cannot get rid of the fact that it was once alive, but in the form of art, it cannot. That is why they are so sad.

Cover Photo: My Pets, 2015

A whirl of quirkiness and tradition | NÁM—Taste of Asia