Although the Hungarian language has so many subtle linguistic nuances, there isn’t a truly powerful translation for the word expat. After all, we are not talking about visitors or tourists from abroad, but about people who live and work here, who know our country, and who have placed their trust in it for the long term. They look at our city from a fresh perspective, bringing experiences from their culture and their personal past, and combining the two in an exciting mix. In our latest article series, Budapest through the eyes of creative expats, we spotlight foreign artists, designers, and creative professionals who have set up their base in our capital.

Written by Lilla Gollob

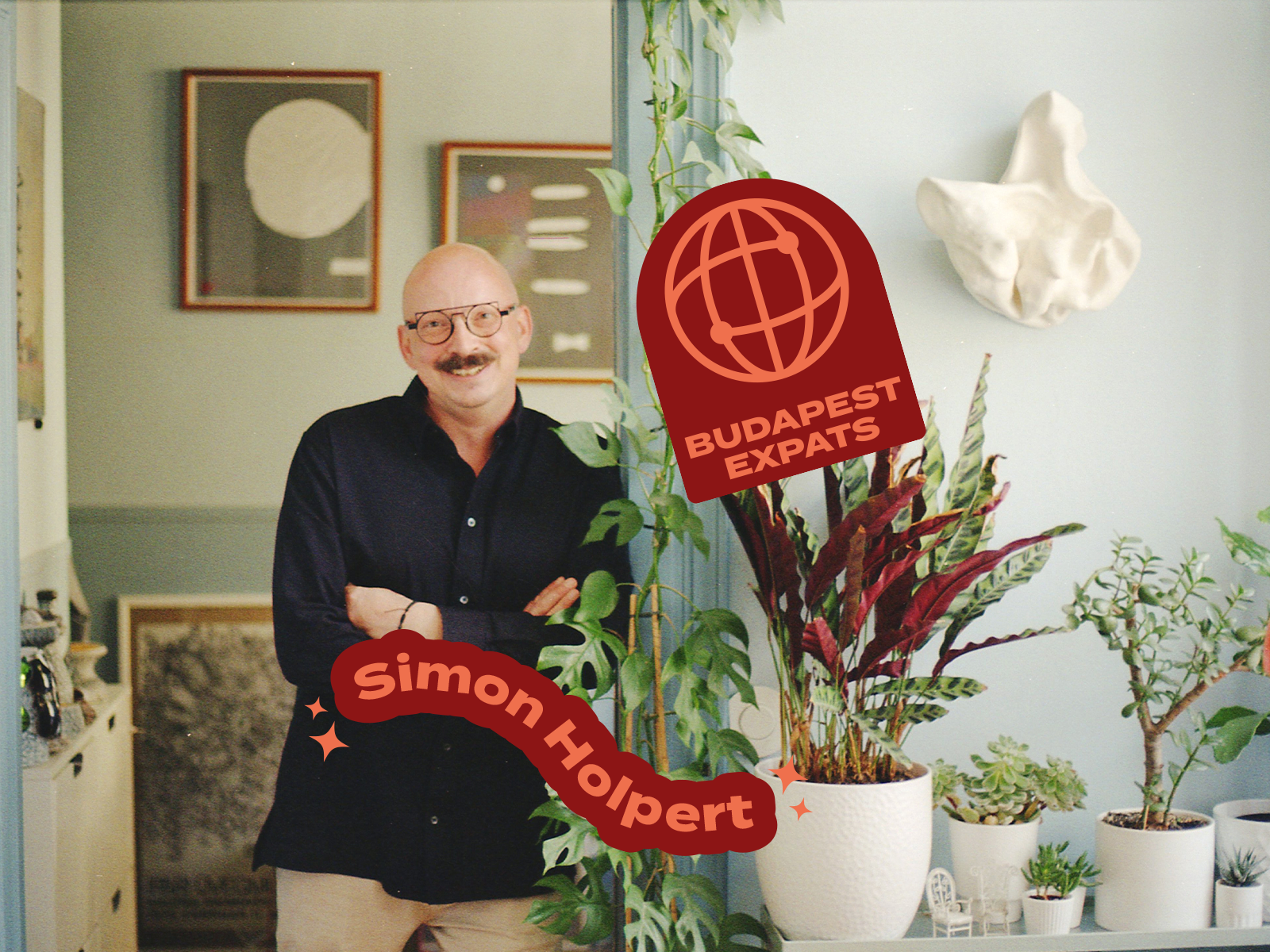

In this third part of the series, we spent a pleasant afternoon with Simon Holpert, a ceramic artist from Paris. We first visited him in his home on Szinyei Merse Street, which resembles a small gallery, packed with vinyl records and his ceramics collection, consisting of his own work and that of others. The interior combines Parisian influences with Hungarian retro, framed by walls in various shades of blue. In this sensitive yet playful arrangement, everything is connected, just like in Simon’s life. Later we walked through the newly opened Museum of Ethnography, where we learned why the Városliget (City Park) is such an important location for Simon. Our inspiring conversation was conducted, quite unconventionally for similar interviews, in Hungarian, the reason for which will be revealed shortly.

How did your story with Budapest begin?

My mother is from Paris, and my father is from Baja (a city in the south of Hungary). He fled to Paris at a very young age and, as he arrived alone, he had to assimilate into French culture straight away. I was born in Paris, by which time my family has fully integrated, and I only spoke some basic Hungarian. For a long time, my only contact with Hungary was the occasional visit to my grandparents in the countryside, and then a day or two in Budapest. In high school, I decided that I wanted to graduate in Hungarian as a foreign language. This was my first big step toward Hungarian culture. Following that, I completed a degree in philosophy in Paris, but subsequently, I became more and more interested in getting to know my roots better, so I enrolled in a Finno-Ugric course. This brought me to the Debrecen Summer School, where I studied the Hungarian language, history, and literature. However, as life would have it, I did not move to Hungary for many years after. I lived for six years in Vienna, two years in Salzburg, and then went back to Paris. I bought my apartment in Budapest seven years ago, originally to come here on holiday, but decided to move here permanently three years ago.

What led you to make this decision and move your base here?

I was born in ’76, and I’m very fond of the time when I used to come here a lot in the summers in my 20s. I was greatly influenced by the Sziget Festival, which back then was called Pepsi Sziget, and that was also when the famous pubs, Szimpla and Kertem opened. A lot of openness and dynamism characterized Budapest back then. I think they are still there today, I like the way the city is developing. The practical background to the decision was that three years ago I had an opportunity at a gallery in New York, but somehow I couldn’t imagine myself there. I also didn’t want to stay in Paris because I wanted to move to a bigger studio, which I couldn’t afford there. Then I had the idea: why not try my luck in Hungary? In hindsight, I think it was the best possible decision. Of course, it’s not easy anywhere, the grass is never greener, and there’s always something to complain about. Nevertheless, I found my workshop here, I feel that there are huge opportunities in the world of ceramics and love has also found me. My parents, although supportive of my decision, never thought I would be the one to come back to Hungary, the one to relearn the language. In the meantime, I think this is precisely due to the openness they taught me as a child.

Do you remember your first impression of the city? What caught your eye?

My first contact with Budapest was with the City Park, which we used to visit whenever we came to see my grandparents when I was little. All the memories I have from these trips are linked to the Andrássy Avenue, the City Park, and the circus and the zoo within it. You know, they often ask kids what they want to be when they grew up, to which I used to answer with ‘the circus’ or ‘the zoo.’ Not a profession, but a complete circus or a complete zoo (laughs). The first thing I noticed when I moved here was the roofs though. You can see the roofs in Budapest. You can’t see them in Paris because of the height, and they’re all grey anyway, which blends in with the grey sky there. It makes me feel like I’m trapped in the city. In Budapest the buildings are lower, there are lots of tiled roofs, and the sky is blue. It makes the city seem more accessible. For me, this is freedom. Even the clouds here have a different shape. You can see this in the paintings of Pál Szinyei Merse, for example, which are exhibited in the Castle. Meanwhile, I still consider myself a Parisian, and it was also important for me that I could find a lot of similarities between the two cities. The Andrássy and the Champs-Élysées, the Danube and the Seine, or the atmosphere of certain districts. I found essentially what I loved there.

Let’s turn a little towards ceramics. How did you get involved in this medium?

I have always been interested in the world of art and when I lived in Vienna I had the opportunity to open a gallery. Then, ten years ago, I went to an open studio day in Paris and met a ceramic artist, Lise Meillan. I really liked what she was doing, so I asked her to teach me. At first, she said no, but after about two months she contacted me and said she was ready. I became her first student. From the very first moment I had a special connection with clay and porcelain, deep down I felt I had something to say with these materials. I immediately thought of sculpture, I saw ceramics as an artistic medium, not from the perspective of pottery. It’s funny though, that Lise is a real “ glaze witch” and I was going in the direction of no glaze. I was interested in the material and the form, and what I could create with my hands. After two years, I was discovered by a Japanese gallery, and then things took off. It is also good to see that ceramics are becoming more and more important in the contemporary art world and that there is a growing recognition of the communicative potential of ceramics. We were recently at the Venice Biennale, where the award-winning American pavilion and the Lithuanian pavilion both exhibited ceramics.

How did your artistic path crystallize? How do you work and where do you find inspiration?

For me, constant research is what is really exciting in ceramics. There is witchcraft in it, but also science, chemistry, and physics. You have to experiment, you have to find out how the material reacts to what, and where the limits are. In ceramics, in my understanding, everything can be a tool: a hand, a footprint, a piece of cloth, a piece of wood, a leaf. Anything. I have no rules.

One of the most essential aspects of my work is that I rarely use glaze. I want to bring the importance of touch back, to start feeling the material again. It’s also particularly important to me because, although I’ve turned to sculpture, I don’t want my work to end up in a display case, where it can’t be touched like museum objects. Rather, I want people to live with the artwork. After all, an art object is almost a pet. You don’t have to walk it, you don’t have to feed it, but you can have a relationship with it. I had a series of so-called ’sleeping sculptures’ where I placed the ceramics on pillow pedestals. A pillow as a pedestal suggests an intimate connection, and you can place the artwork on it in different ways to create interaction. The glaze also covers up any imperfections, but I don’t want to cover anything up. Here is what came out of my brain and my hands in the raw. Of course, that doesn’t make them perfect, but what is perfect in today’s world? The fact that I do experiment with glazes sometimes is because we are in Hungary and there are opportunities here that I have not encountered anywhere else. I usually make hollow porcelains, which are technically quite difficult to create. Porcelain is the most difficult material because it cracks, it deforms, it dries quickly, it is not elastic. That’s why you can see the hand and fingerprints, the difficulty, the force that’s applied to my objects.

I essentially think in series, but there is always spontaneity, an active conversation with the material. My series are based on different themes. During Covid, I made Blue Moon, with a new type of clay and glaze. It’s about love and longing, it has the sky and stars in it. The Missing Part series without glaze is about absence, about someone being gone, and how we can get back to touch. I recently did a raku series and I also take a more commercial approach to creating more decorative objects. For example, I will soon present my first porcelain necklace collection.

What is it like to work as a ceramic artist in Budapest? What is your relationship with the ceramic community here?

I’ve been in Hungary for three years, two of which have been during Covid, but despite this, two big events have happened in my world of ceramics. Last year, I was selected to participate in the National Biennale of Ceramic Art with my Blue Moon series, which included an exhibition at the Zsolnay Quarter. And this year, two pieces from this series were also selected for the first contemporary auction of the Nagyházi Gallery and Auction House. I also have a very good relationship with the ceramics community, and even though I came from abroad, and not from MOME or the University of Pécs, I was accepted immediately. In fact, that’s what I usually hear them saying, that sometimes they envy my freedom, the way I communicate with ceramics without any constraints.

Several times a year I visit the International Ceramics Studio in Kecskemét, which is like a “ceramics monastery”. Students come here, but also older, renowned Kossuth Prize-winning artists as well as foreign artists. There are studios, accommodation, and all kinds of technical facilities (raku, gas, and wood-fired kiln) there. It’s a huge luxury to be able to try out so many things only seventy kilometers from Budapest. I have never seen anything like it anywhere else in Europe, so close to the capital. It’s like a big family, everyone knows everyone.

Your new workshop will open in September. What are your plans for it?

We found the space the day before the pandemic broke out, in an old restaurant at 47 Damjanich Street. Hence the name ‘Atelier 47.’ I wanted to emphasize the French aspect. We are still in the construction phase and plan to open in September. It’s quite a big space: in the back will be my studio where I can create, and in the front, I want to create a sculpture showroom, a cultural center where people can meet. I would like to organize international exhibitions with curators, not only in the field of ceramics but also in wood sculpture, metal, or any other material. We also plan workshops and private dinners among the sculptures, like in a home restaurant. These programs will be managed by my partner, who will be in charge of marketing.

We’re in your favorite Budapest venue, the new building of the Museum of Ethnography. Why is this place important to you, why do you like coming here?

As I said before, the City Park is a very important place for me. My childhood memories are connected to it, my apartment is nearby and my new workshop will be right around the corner. And with the recent developments, the Park is playing an increasingly central role in Budapest. The Museum of Ethnography is therefore important partly because of its location and its proximity. On the other hand, they have set up a free-to-visit ceramics exhibition, with objects sorted by country on one wall and by use on the other. It is very interesting to see what each country did, when, and why. You realize that there were already sculptural, contemporary, and organic features in folk art. I think it’s a pretty refreshing experience, and since my workshop will be just a few minutes away, I will be able to give a lecture or guided tour on the evolution of ceramics here.

Favorite Hungarian food: Emperor’s Mess (a fluffy shredded pancake—the Transl.)

A Hungarian word you know and love: Szabadság, meaning “freedom”

Best season in Budapest: All of them

A song that describes your mood lately: Libre – Angele

A color you really like lately: Blue

Simon Holpert | Facebook | Instagram

Photos: Dani Gaál

This raft hotel can make our childhood dream come true

Scenic lakes in Eastern Europe | TOP 5