We would have been very surprised if in 2019 someone had predicted empty offices and Zoom fatigue for future workers. What is next after the sudden yet not unexpected changes? What will shape the office layout of the future: hybrid working, escaping digital overload, or metaverse? How do architects, journalists, researchers and creative professionals see it? We explore all this in the first Hype Lab article of the DIALOG thematic month.

The golden age of hybrid working

We’ve heard, read and experienced first-hand that Covid-19 has shaken up the office culture. In fact, the changes had already begun long before the pandemic, which then only accelerated them. More and more places are scrapping private desks and introducing hot-desking; lockers are being installed where employees can keep their personal belongings; meeting rooms are being equipped for hybrid meetings—more cameras, microphones, screens are expected. The changes will also mean an increased demand for data: under the pretext of protecting against Covid-19, office owners will be able to monitor workers’ activity on everything from who is in which room and when, to the air quality in meeting rooms. According to real estate developers and office furniture companies, the office will not disappear as such, only transform. Meanwhile, some surveys show that 40% of US employees would rather look for a new job than return to the office. If there really is a transformation, the key is for the office to become a space for collaboration, social events, brainstorming and meetings, while focused individual work remains at home.

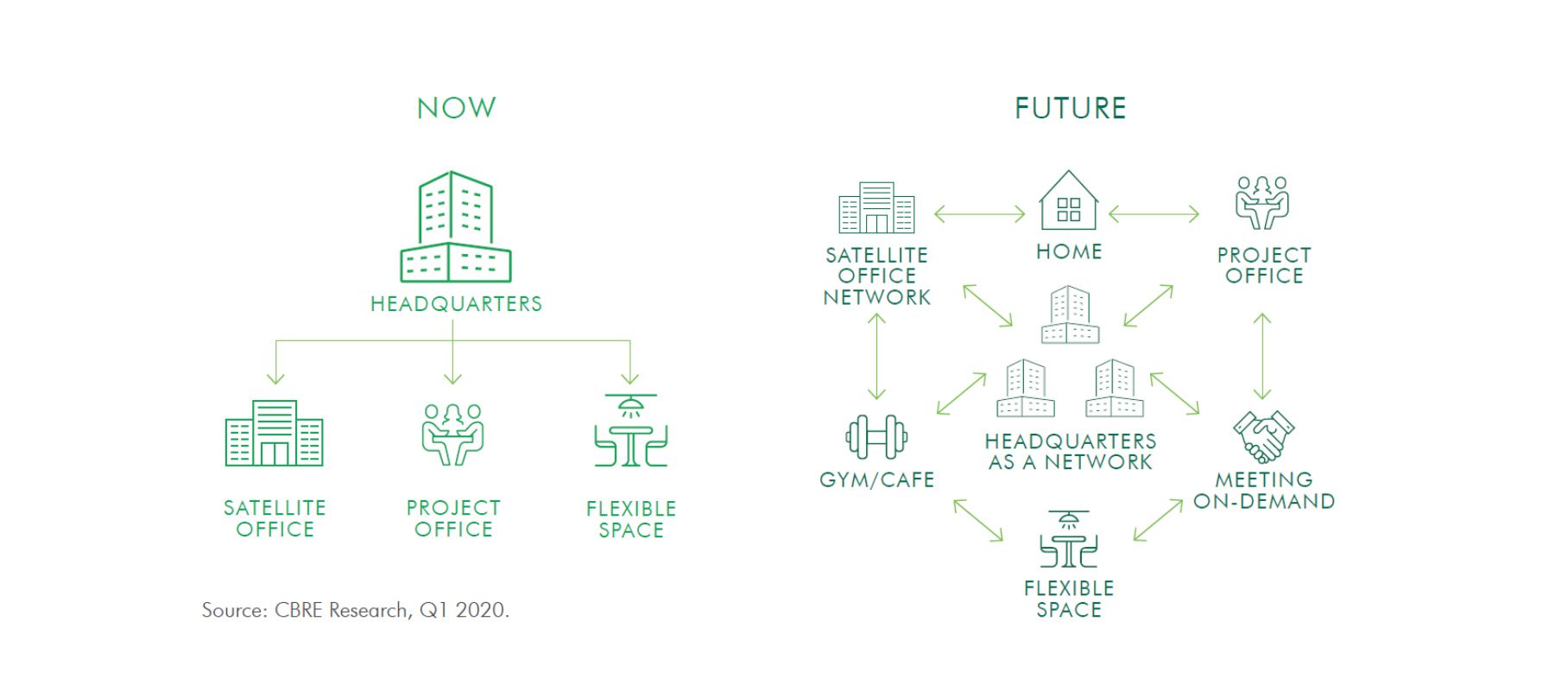

As a consequence, the size of the offices will also change. We last reported on the construction of the Tour Triangle skyscraper in Paris, where the mayor of the district, Philippe Goujon, is opposed to the construction work, if only because the changed working conditions brought about by the pandemic do not justify erecting office skyscrapers above the city. Since hybrid working does not require all workers to be in one place at the same time, in 2021 more workplaces will be replaced by smaller offices, reducing the company’s costs and ecological footprint. There is also a growing number of companies opting for the hub-and-spoke model, whereby a central downtown hub is reserved for office-wide meetings and several smaller spokes are designated as working locations around the city. These could be satellite offices, a coworking office’s free workstation, or even cafés or home offices. But the sight of a vacant office isn’t the only thing we found hard to imagine in 2019—Zoom fatigue wasn’t in our dictionary either. It seems reasonable to ask: in the long run, do the benefits of remote working outweigh the negative effects of the digital revolution on physical and mental health? Is hybrid working really the golden mean? Or will the office of the future sway the balance of the analog-digital axis? And if so, which way?

The analog office, where the employee escapes from electronic gadgets

In 2015, Fast Company asked architectural firm Perkins+Will to share its vision of what offices will look like in ten years’ time. Their vision was based on the idea that with the rapid advances in technology, we will be able to work anytime, anywhere, and that offices will lose their former function and become something else entirely: a space of retreat. One part of the concept, dubbed the analog office, is the so-called generative space, where electrosmog screens help you escape from endless calls and notifications. The indoor-outdoor space is designed to function as a community space where employees come for meetings, brainstorming sessions and socializing. They can take notes with pen and pencil on paper and other writing surfaces, enjoy a cup of coffee between meetings made by a colleague who used to work as a barista, or stop by the local pop-up store of a colleague who makes knitwear in her spare time. While the generative space has the feel of a market or a mini neighborhood, the regenerative space is designed for individual work: here, laptops and mobiles are ready to use, and focused work is facilitated by one-person workstations. According to Perkins+Will, a climbing wall also deserves a place here, as wall climbing helps to strengthen individual focus.

There is something about the seemingly naïve vision of the analog office that is eerily similar to the offices of the American advertising giant TBWA\Chiat\Day back in the 1990s. Jay Chiat wanted to reform the workplace, and his first experiments were based on the Frank Gehry-designed “binoculars“ building. Chiat was driven by the idea of collaboration and free movement, so he removed walls and work booths. He did away with private desks: when workers entered the office, they were given a phone and a laptop, and then sat wherever they wanted. Employees stored their personal belongings in lockable cabinets. The business world reacted quickly, referring to it as a “virtual office“, but according to journalist Nikil Saval, the revolutionary arrangement has not stood the test of time: more and more people were hired who didn’t know where their place was and went home. Managers could not find their subordinates, the work was not getting done. On a second attempt, Clive Wilkinson redesigned the company’s office in the iconic yellow building in a more modest edition (if you can call a workplace with a basketball court modest). This office, similar to the Perkins+Will design, was more like a mini-city than a classic workplace—different work stations and recreational spaces set up on different levels of the building.

The iconic office defined Wilkinson’s subsequent work, and the office he designed for Google carried on the same spirit. David Sax, a journalist for the New Yorker, made an interesting observation about the ’ analog workspaces’ that Silicon Valley tech companies have since favored:

”The first, which I saw at Yelp, was creating a strong corporate culture, bound by real relationships, in an industry where the nature of the work, and the tools used to do it, naturally lean toward isolation. Offices that appeared at first glance like adult play rooms […] were in fact carefully designed to maximize analog interactions, with an eye toward fostering the company’s culture of innovation and productivity. The other main reason why overtly analog workplaces dominated digital tech companies was that […] software companies are by their very nature ephemeral. Corporate headquarters are their one presence in the real world, serving as embassies to the analog realm, where the virtual brand can transcend into the physical,” says Sax, who did not think at the time that in 2021 it would be a Silicon Valley software company, Facebook, that would come up with the seemingly utopian idea of offices in the metaverse.

VR glasses could be the way to the office of the future

Home office and community experience (or the illusion of it) can be combined by Mark Zuckerberg’s idea of working in a metaverse. In five to ten years, the Facebook founder says, working in virtual reality will be as common as sending emails from your mobile phone today. Utopian videos suggest we could soon be checking in to the office through smart glasses while sipping coffee at home in sweatpants, or projecting a hologram of a colleague in front of us to discuss the details of our latest work project hovering virtually above our desk.

Meta’s VR service evoking working environment is the Horizon Workrooms, which the company has been testing for some time, and at its launch in August this year, several journalists were invited to meet Zuckerberg in the metaverse via their Oculus VR devices. So we won’t be going to the office anymore?—a CBS reporter later asks the father of Facebook, who says that the less extroverted are already reluctant to return, and the metaverse opens up the possibility of the best job opportunities for people who live in another part of the world with their families and would stay that way. This idea is echoed by the optimistic views of Justin Spitzer, screenwriter of The Office, on the jobs of the future:

”Geography will no longer be an impediment for employees to find the best jobs, or employers to find the best workforce, and commutes will be no longer than the amount of time it takes to log in to the network. Employees will appear in this virtual world as whatever avatars they choose. Since everyone’s real-world appearances will be hidden, there’ll be no more discrimination based on race, age, gender, or disability. Our avatars will grow ever more adventurous. You might look into the next cubicle and discover Cthulhu checking your expense reports. Or walk past a conference room and see George Clooney giving a presentation to Margot Robbie, Genghis Khan, a cartoon pencil, and a second George Clooney.”

But in an earlier interview, futurologist Árpád Rab warned us against the illusion of achieving social equality. ”We like to believe that a digital world will bring digital democracy and utopia—the same could have been thought of the internet back then. […]Social inequalities are actually reproduced and exacerbated by these technologies,” the researcher said after Zuckerberg’s announcements. Beyond the community, the changes affecting the individual are not encouraging either: how can our sense of self be transformed if we do not represent our own self 8-10 hours a day, but create avatars to do so? While we can combat Zoom fatigue in an office with a VR experience, and replace the laptop speaker to hear our colleagues’ voices as if they were coming from across the room, little is known about the impact that a workday spent online can have on our spatial awareness, mental health, relationships and personal data security.

Rediscovering an old ingredient: water caltrop reimagined

Revolutionist in the domestic advertising market