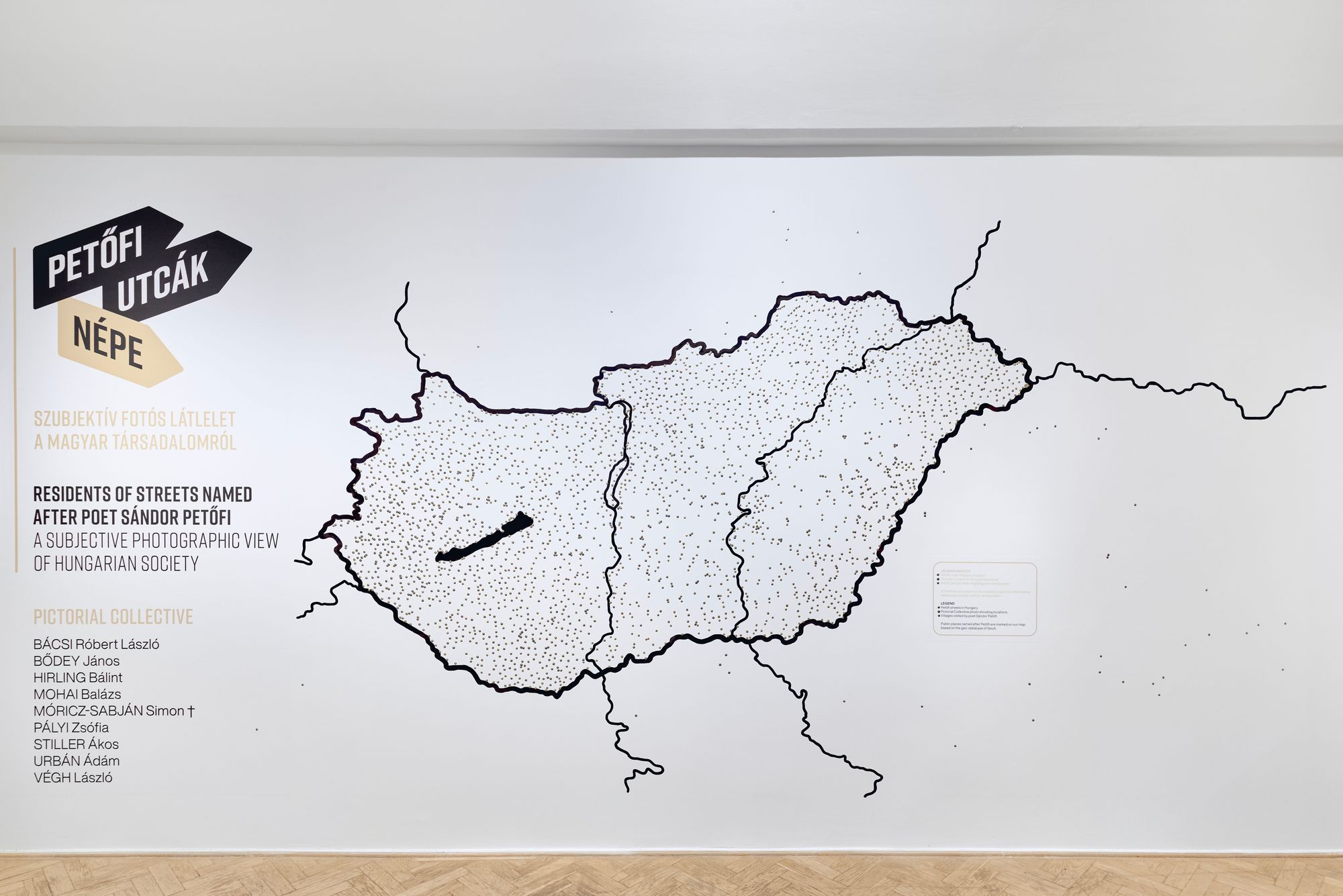

In a long-term project, the Hungarian documentary photography group Pictorial Collective captured the residents of streets named after Sándor Petőfi, providing a subjective snapshot of contemporary Hungarian society. We asked two members of the collective, Róbert László Bácsi and Balázs Mohai, about organization, travel, special encounters, the Hungarian countryside, and Petőfi.

Poland’s Adam Mickiewicz and Ukraine’s Taras Shevchenko are on a par with Hungary’s Sándor Petőfi; the romantic, controversial Poet with a capital P, who fought for the nation’s freedom and was exploited and used by various political regimes. In Poland, more than 1,100 streets are named after Mickiewicz, and in Hungary more than 2,800 after Petőfi—perhaps this number is an indication of the extent of the Hungarian poet’s cult.

You’ve been to many places, and you’ve traveled a lot. How did you organize your trip?

Balázs Mohai: A lot of consultation and planning preceded the actual work, and before the photo shoot we had several conversations with the curator of the exhibition, István Virágvölgyi. Each of us was assigned a few areas, which we divided up according to interest, local knowledge, and other criteria. There were some more popular regions, but one of the most exciting things about this project was that we could go out and explore the unknown. Let’s face it, there aren’t many people who know their own country by heart, and even fewer who know every Petőfi street. I chose the county where my family comes from: I had some experience there, but I wanted to see more. My other choice was one where I had hardly ever been and had only typical preconceptions about what I would see. And of course, we also moved around spontaneously, visiting Petőfi streets and Petőfi memorials when we were traveling for business or pleasure. Emese Bíborka Szakács also helped us, for example, she put everything on a map, so after a while, we could see where we had been.

The project took about a year and a half. In the meantime, did you keep in touch and talk to each other about the pictures?

B. M.: We communicated constantly, we had meetings and online discussions, we showed each other our pictures. We also had long phone conversations with Simon Móricz-Sabján, who has since passed away, but they were the most intense during this period. Once I was caught in a two-day storm somewhere in Borsod County when I was not making any progress with my work anyway—he kept me going, gave me ideas from afar, but above all he listened to me and pushed me forward. But everyone could be counted on. That is the forte of the Pictorial Collective. We supported each other without professional jealousy and were happy if someone brought a good picture from somewhere.

R. L. B.: We were constantly looking at who was doing what while we were taking the pictures. Of course, there were times when you didn’t really have a clue what to do with a particular location or couldn’t find anything interesting. Many times it was enough just to tell the other person to let go of all expectations and not to conform, but just do what they felt like. We are also a collective to help each other in our work—it was good to have these conversations and inspiring to know that a teammate was now away for a few days doing this again. At those times I was always looking forward to going myself.

How did you photograph people? Did you always talk to them?

B. M.: In all cases, a conversation preceded the photo shoot, or at least there was always contact after the photo was taken. The aim was not to take street photos but to really immerse ourselves in the stories. That’s not the focus of the exhibition, but we are also planning a follow-up to the project, where the backstories can have more emphasis.

Did you have memorable encounters or stories during your travels and photo shoots?

B. M.: There is a story with every picture taken, but there are just as many stories with the untaken ones. We’ve been to thousands of places where we’ve tried, talked, been let into courtyards, living rooms—but then either the person didn’t want to be included or wasn’t visually interesting, so no picture was taken, or maybe they were left out of the selection. In Petőfi Street in Tiszaug, I had been searching in vain for hours for a subject, when suddenly a three-wheeled vehicle rolled out in front of me, with Ms. Mária in a visibility vest with Petőfi Népe (Petőfi’s People—the Transl.) written on it. For decades she had carried the Petőfi Népe daily newspaper. And in Miskolc, I asked someone about a indistinctive memorial plaque, asking if they knew anything about the connection between the place and Petőfi. They told me to go up to their office and they would show me where the poet slept. In the completely renovated house, they showed me to a storage office. It was spooky to see that corner between the ancient walls.

R. L. B.: We came across so many interesting stories and people. I was walking through a small village and saw a very cute little farmhouse, but there was no one around. A couple of houses away, there was a big commotion in a yard, so I rang the bell and within moments I found myself in the middle of a pig slaughter. Eventually, I was taken to the farmhouse where I was able to meet 92-year-old Ms. Margit—she had been robbed a few weeks ago, so was a bit wary at first, but eventually let me in and I could take photos. Elsewhere, I became so close to a family that I was invited for lunch, went with their granddaughter around their farm, and we’ve been corresponding ever since.

There are also quite stark contrasts in some of the public squares named after Petőfi. What kind of image have you drawn of the Hungarian countryside?

M. B.: It was a wonderful journey of a year and a half, like a roller coaster. Beautiful landscapes, grey dullness, decaying memories. Kind people moved to tears, and excluding grumpiness. Happiness in incredible poverty and harshness in wealth, or a mixture of both. This project does not answer any questions, but I hope it will make you think, open your mind, and lead you on a journey: from now on, let all the adventurous go out and observe some Petőfi streets on their way. All in all, the many mixed experiences are as grey as our own lives. But we are better off if we do not see it that way.

R. L. B.: My personal experience is that there is basically quite a high level of poverty in the country. We tried to make sure that this material was not just about that, but it was difficult. There is a lot of emigration, depopulation in many places, but we often met people who, despite being poor, are living their lives, trying to live well. In any case, I was impressed by the ingenuity of the Hungarian people. The humor was also essential, so that when you see a picture you say, “well, that’s a typical Hungarian” and smile a little.

What do you think Petőfi and his poetry mean to the Hungarian people today?

R. L. B.: I often met people who were proud to live on a Petőfi street, and these people were obviously familiar with his poetry. There were those who said that what Petőfi wrote two hundred years ago and what he fought for is, unfortunately, more relevant than ever. I generally felt that Petőfi’s name was immediately associated with freedom or the struggle for it. But then there were those who I don’t think even thought about it until we came along.

What is your favorite poem or line by Petőfi?

B. M.: I myself am an extremely patient person, yet this is how my friendship with Petőfi began:

“Türelem, te a birkák s a Szamarak dicső erénye, Tégedet tanuljalak meg? Menj a pokol fenekére!” (“Patience, thou glorious virtue of the asses and the sheep, Shall I learn thee? Go to the depths of hell, I weep.”—free translation)

R. L. B.: I often preferred Petőfi’s poems that were not taught in school, they were an incredible reflection of how much a young man like him struggled with himself and the world—as young people do today, but in fact, everyone does. In 2021, when I was in Armenia, I met an old man who, when he found out I was Hungarian, told me that his favorite poet was Petőfi and recited his poem The Maniac. I have cherished that poem ever since, because it has a lot to say about the way the world is, and it perfectly describes the anger I feel about it.

“Why laugh I like a fool here, why?

I should lament and loudly cry,

The world’s so bad that even the sky

Will often weep that it gave birth

To such foul creatures as the earth.

But what becomes of heaven’s tear?

Falling upon this earth down here,

Men tread upon it with their feet!

God’s tear becomes – mud in the street.”

(Translation by WM. N. Loew)

Pictorial Collective | Web | Facebook | Instagram

Pictorial Collective: Residents of streets named after poet Sándor Petőfi – A subjective photographic view of Hungarian society

Capa Center (8 Nagymező Street, 1065 Budapest)

Until October 1, 2023.

Exhibiting photographers: Róbert László Bácsi, János Bődey, Bálint Hirling, Balázs Mohai, Simon Móricz-Sabján †, Zsófia Pályi, Ákos Stiller, Ádám Urbán and László Végh, members of the Pictorial Collective

Curator: István Virágvölgyi

Cover photo: © Róbert Bácsi László

Two big favourites meet as LEGO launches their latest Harry Potter-inspired product