Croatian photographer Domagoj Burilović has been photographing the once glorious, now crumbling buildings of the Slavonia region of Croatia for years. In addition to showing the unique architecture of the houses, he also reflects on social issues such as the exploitation of nature, colonialism, and emigration. The series won 1st place at the 2022 Sony World Photography Awards. We asked Domagoj about making the Dorf series, winning the award, and his future plans.

How did you find the buildings and landscapes that are featured in the Dorf series?

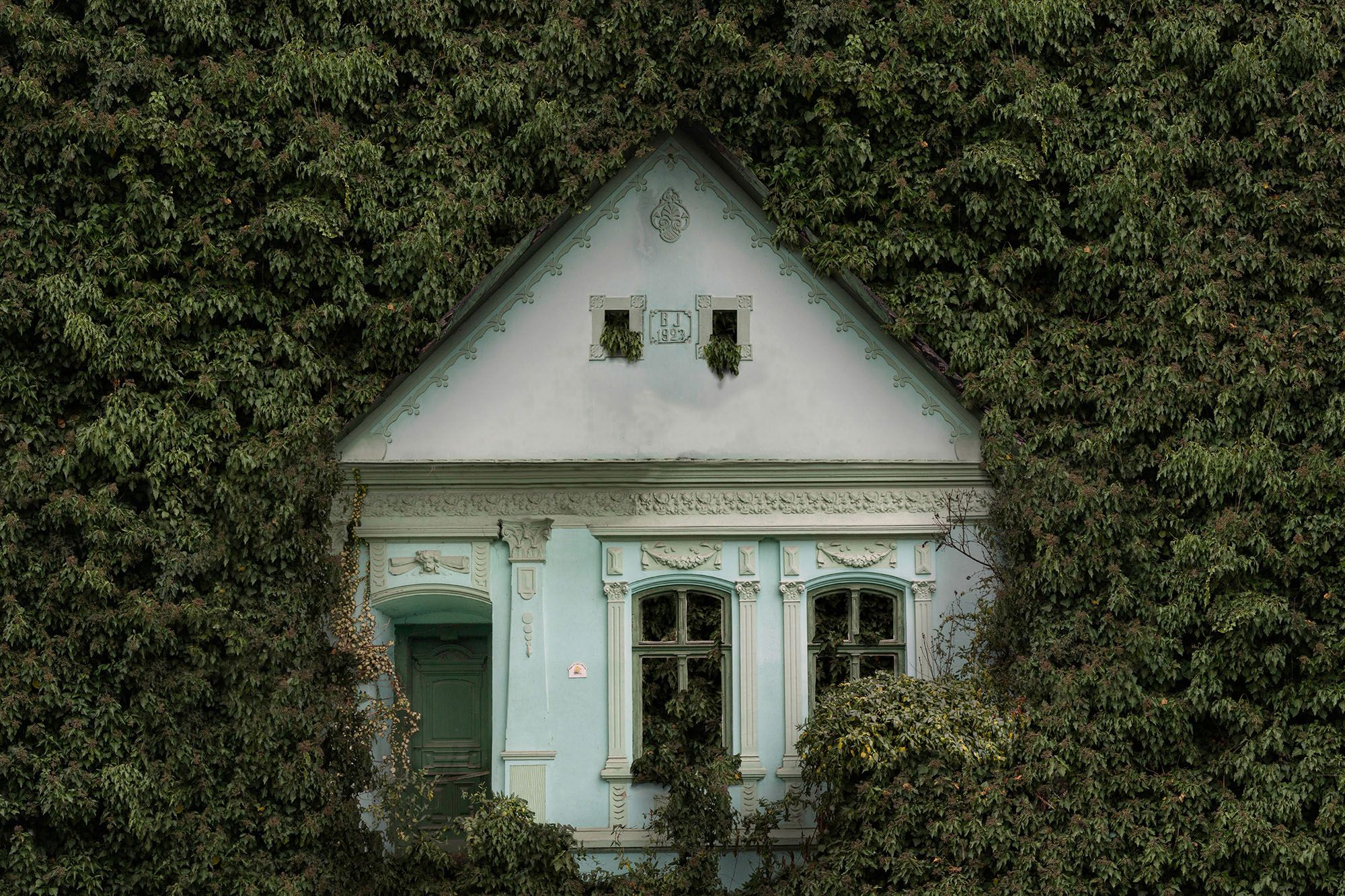

These buildings are found in almost all the villages in the area of Eastern Slavonia where I live, so I have known them all my life.There are many of them, but rarely in their original condition, which is the criterion by which I choose them to photograph. Forests and vegetation were also photographed in the local area of Slavonia. Of course, they were combined into photos by photomontage to create a context of decay and abandonment of these houses.

What was your work method during the Dorf series?

This series did not start as an art project. In the beginning, I was just playing with the visual elements of historic village architecture. However, as I slowly began to research the history and cultural significance of this architecture, I realized that it could be an interesting story. Although such architecture would be adequate for a standard photographic typology, I did not want the series to be reduced to a mere listing of buildings, but instead, I wanted to create some interesting and visually dramatic situation in which the photos would present the architecture and the society within which they were created and decayed. The series was created over a period of 2 years, during which time I researched different visual solutions, and this final one was created by a combination of circumstances—in post-production, each object had to be cleaned of various visual obstacles (cars, poles, signs, trees, bushes...), however, one house was so overgrown with ivy that it was impossible to reconstruct the entire house and remove the overgrown vegetation. Then it occurred to me that instead of removing greenery, I should surround everything with greenery as if nature were “swallowing” the buildings. This is how this version of Dorf was born. For this series, I chose the most interesting buildings, but I had to make sure that the colors, tones, and shapes match the plants. This conformity is subtle but important for visual harmony.

What was your goal with this project?

In my artistic work, I have been dealing with the problem of emigration from Slavonia for years. Slavonia is an agricultural region in Croatia that was hit the hardest by the war in the 90s and the decline of industry. For this reason, in 2013, when we entered the EU, the biggest wave of emigration started from here. 25% of the (mostly young) population moved out, and together with natural mortality, this region slowly becomes almost empty. Slavonic villages, which were historically large and had an important agricultural factor, are most affected by this process because they do not provide a sufficient quality of life. Through historical village architecture, I present the story of the fate of villages in Slavonia and the region itself. This type of house was created at the end of the 19th century when this region experienced an industrial boom and was inhabited by different nations of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy: Germans, Austrians, Hungarians, Serbs, Slovaks, Ukrainians, Jews, and Croats. It was the German colonizers who made the biggest impact on local life and created this type of building, which was taken over by all the other peoples in the area. These buildings have become an important part of the historical and cultural identity of the area, and today they are empty, uninhabited and decaying. It is an irony of history that once Germans immigrated to Slavonia and raised the quality of life, and today Slavonians go to Germany in search of a better life. The aim of this project was to point out the problem of emigration, but also to point out the importance and significance of this architecture as well as the disappearing villages.

Why is the title in German?

‘Dorf’ is the German word for village. I use the German word for the name of a Slavonian village to indicate the influence and interweaving of German culture in Slavonia, but also to highlight the irony of the settlement of Germans in Slavonia and the present-day emigration of Slavonians to Germany.

What was it like to win 1st place in the Sony World Photography Awards? How has it changed your career?

Winning the award was certainly an exciting experience. I got the opportunity to participate and become visible on a wide international scene, to see how the art world works in a much wider context. As part of this award, the works traveled to numerous exhibitions around the world, so I got in touch with many people and realized some collaborations. In the context of my artistic career, this award and this project were certainly a turning point and a move to a higher level—I have much more artistic engagement, collaboration, and media activities. Not much has changed in my private, everyday life because I don’t make a living from photography and art. I work as an art teacher, I have two small children and I have a lot of work to do with building my own house, so my artistic activity is now even more of a commitment, but it is also a pleasure that I would not give up.

What are your plans for the future, and for the next photo series?

For now, my priority is to continue working on the Dorf project. In the process of working on this series, some buildings collapsed very quickly after taking photos of them, and I realized how quickly this architecture disappears. I set myself the task of recording as many of these objects as possible in order to preserve them at least in that way. In this way, this project will continue for years in terms of conservation, documentation, and cataloging of this specific architecture. At the same time, I will work on their artistic interpretation to raise awareness about them as well as about the problems of this region. I am also planning a series of photographs in which I would create some fictional mental landscapes of people who remained to live in Slavonia as a desolate area where everyone has close people who left this land. I would visually intertwine this with the swamp and forest landscapes of this area and the first civilizations that inhabited Slavonia 7,000 years ago.

Combining the old and the new—Polish Army Museum

Satin, Soil, Stomach—you can visit the hypest exhibition of Košice for two more weeks