The flame-resistant dishes frequently referred to as the dream of housewives once came from the GDR – this is where the name of these glass baking pots available in various shapes and sizes came from: “jénai” (Hungarian for denoting something originating from Jena, Germany – the translator’s note). One thing not many people happen to know, however, is that there was a similar dish set manufactured in Hungary, by Karcagi Üveggyár (Karcag Glass Factory). In the latest episode of our Object Fetish series, we go after the “Hungarian jénai”, and will also reveal what designers Wilhelm Wagenfeld and Katalin Suháné Somkuti have in common.

A few weeks ago, in one of the classrooms of Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, photos of two very similar glass objects were placed next to each other. The students attending the Artwork Description course learnt about the institution of the Bauhaus that day, and then the lecturer pointed to the glass objects displayed on the slide and said: “Trick question: which one was made earlier?. The students sitting in the room looked at the screen, eagerly – there was silence in the room. The professor also added that one of the objects was not even made in the Bauhaus, but is nevertheless related to it. The quiet felt even more thick and palpable, so the professor continued: “Well, what could this object possibly be? How big is it in reality? What can it be used for?”. The students shared their guesses, including answers like: “perhaps it was used for storing”, “it can be closed”, and then a boy said: “they look a little bit like those jénai dishes”.

What these special objects were, where and when they were made – I will not tell you at this point. Nevertheless the guess of the boy who thought of the jénai glass containers was right. The story of the Termover heat-resistant dish set also started in Jena. Every decent Hungarian housewife refers to the round or somewhat rectangular glass vessels of various shape and size that could not only be used for cooking, but for serving the dishes, too, as “jénai”. And why was this a landmark solution in its era, you ask?

The city of Jena in Germany is indeed the very first thing that could come into our minds in relation to heatproof dishes. These glass dishes were there in almost every household all across Europe from the thirties on, and they still form an inseparable part of our kitchens to this day. The majority of the household glass containers produced by the glass factory in Jena were designed by German designer Wilhelm Wagenfeld, who studied in the Bauhaus, in Weimar, in the László Moholy-Nagy’s metalworking workshop between 1923 and 1925 (Éva Horányi: „Tojásfőző az értéktárból”. (Egg boiler from the vault) Artmagazin, 2019. Volume 17, Issue No. 5, pp 12-16 Instead of continuing his studies in the Bauhaus moving to Dessau, Wagenfeld travelled to the city of Jena near Weimar, and started to work in the Schott & Genn Jenaer Glasswerk glass factory operating there, from 1931.

The company has already started manufacturing heat-resistant borosilicate glass products in the 1980s, but at that time these were not used for household purposes, but for optical and laboratory glasses, thermometers and glass shades for gas lamps. With Wagenfeld’s arrival, many new groups of objects appeared in the selection of the factory: first the filigree tea pot was made, followed by the glass containers of various shapes and sizes.

What was the products of the Jena glass factory for Europe, it was the glass objects of Corning Glass Works titled PYREX for America from 1915, but one can also find a factory experimenting with heat-proof glass closer than that: Kavalier in Czechoslovakia, for example, established in 1837 in the town of Sázava. The Czechoslovakian borosilicate glass serving household purposes was born much later than the German and American “brothers”, in 1958, owing to Miloš Bohuslav Volf, and was distributed under the name Simax. The Hungarian audience could also meet these dishes, according to the media outlets of the time: “The Simax fire-proof cooking glass differs from other household vessels used for cooking, for example, the enameled, stoneware, porcelain, metal and plastic vessels in that it is more transparent and is not degradable due to its chemical characteristics. An additional unsurpassable advantage of the same is that one cannot only cook in it. It is also suitable for serving the dishes” („Korszerű edényt a háztartásba”. (Modern dishes in the household) A Hét, May 7, 1977, p 22)

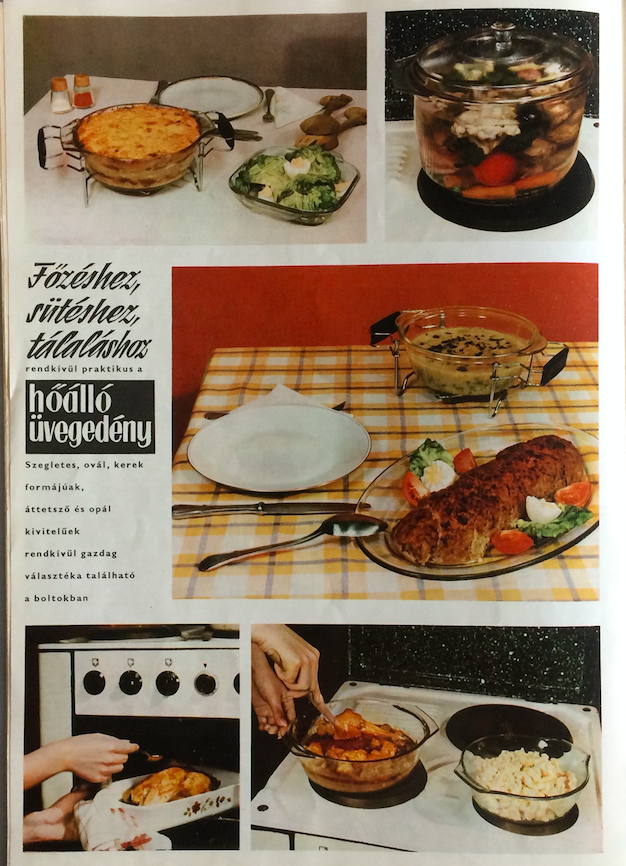

Heat-resistant glass pots have numerous favorable features – the daily and weekly magazines of the era also tried to highlight these, thus raising the attention of the potential audience (primarily housewives). They highlighted, for example, that owing to their use of materials, they do not give any kind of off-flavor to the dish, and due to their excellent thermal properties and smooth surfaces, the meal is less prone to burning than in the case of metal vessels, for example. They also highlighted the practicability of using these heat-proof sets for the reason that one can monitor what happens in the pot due to their transparency. The users also received practical instructions for how to use the utensils defined as novelty: this way, for example, they recommended the models with a round base for cooking, and they also claimed that “the heat-proof glass pot should be heated evenly, therefore if you cook on open fire (gas stove), you should put a metal sieve between the pot and the flame” („Főzéshez és felszolgáláshoz”. (For cooking and serving). A Hét, March 9, 1976., p 26).

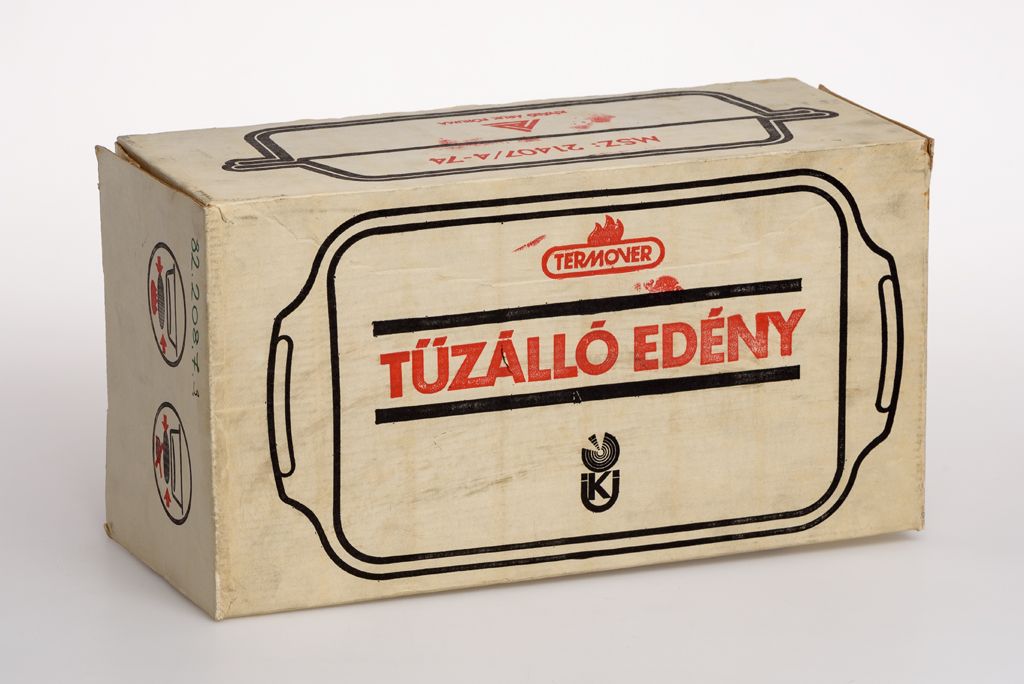

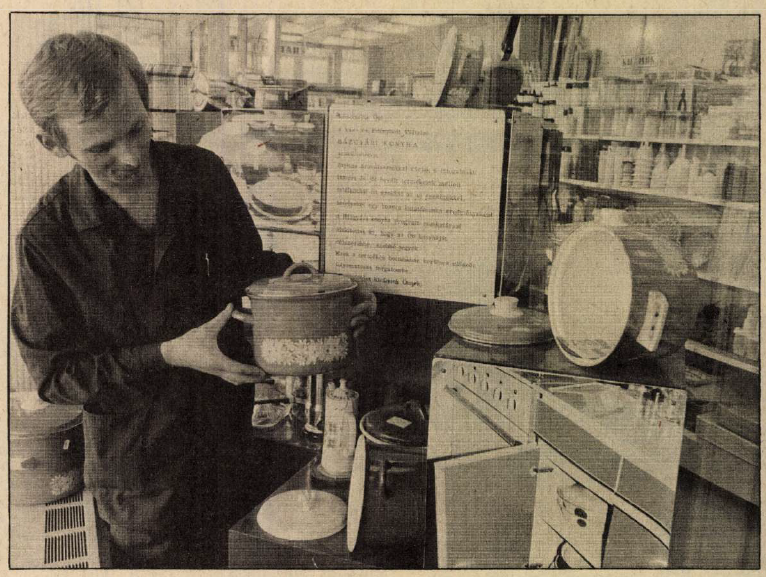

In addition to the jénai coming from the GDR as well as the Czechoslovakian Simax and the “Soviet sets illuminating in green”, heat-proof vessels manufactured in Hungary also appeared on the market. The glass factories in Karcag and Nagykanizsa were already mentioned as manufacturers in the issue of Magyar Ifjúság released on May 5, 1968, and in April 1976, Dezső Sárközi, the managing director of Finomkerámiaipari Művek (Fine Ceramics Works) reports the following: “The heat-resistant household dish set will also become popular, it was a missing item in Hungarian trade, and the Hungarian audience could only purchase it as a foreign product until now. The new product of the factory in Városlőd will be available from the second half of the year” („Homokból valuta. Színes pirogránit díszíti az aluljárót.” (From sand to currency. The subway is decorated by colorful pyragranite) Esti Hírlap, April 15, 1976, p 3). Out of the factories mentioned, it was the Karcag Glass Factory that offered the highest hopes, and within the walls of which the “Hungarian jénai” was actually born: named Termover, this dish set was officially labelled as a heat-resistant dish (as demonstrated by the packaging).

The Karcag Glass Factory started its operation in 1939. The twelve factory units under the control of the Üvegipari Művek (Glass Industry Works) were all specialized in different product types, thus for example the portfolio of the Salgótarjáni Öblösüveggyár (Salgótarján Hollow Glass Factory) mainly included glasses, chalices, and the “Tempress” heatproof glasses, the Ajkai Üveggyár (Ajka Glass Factory) manufactured glass bowls of diverse patterns and sizes, the Nagykanizsai Üveggyár (Nagykanizsa Glass Factory) produced ampoules, thermoses and inserts (as we have already elaborated it in a previous Object Fetish episode), while the cosmetics packaging container of Helia-D was manufactured by the Tokodi Üveggyár (Tokod Glass Factory).

In Karcag, serious experimentation took place since the launch of the factory, also considered important by the administration of the time: “In the second year of the five-year plan, scientific research will be expanded in the Karcag Glass Factory. With a HUF 1.5 million investment, they will set up a research laboratory and an experimental melting furnace” (Népszava, July 31, 1951, p 4). The founder of the factory, the later Kossuth-award winning chemical engineer Zoltán Veress developed the manufacturing of the heatproof glass dubbed “ergon”, the large-scale production of which took place within the walls of the factory.

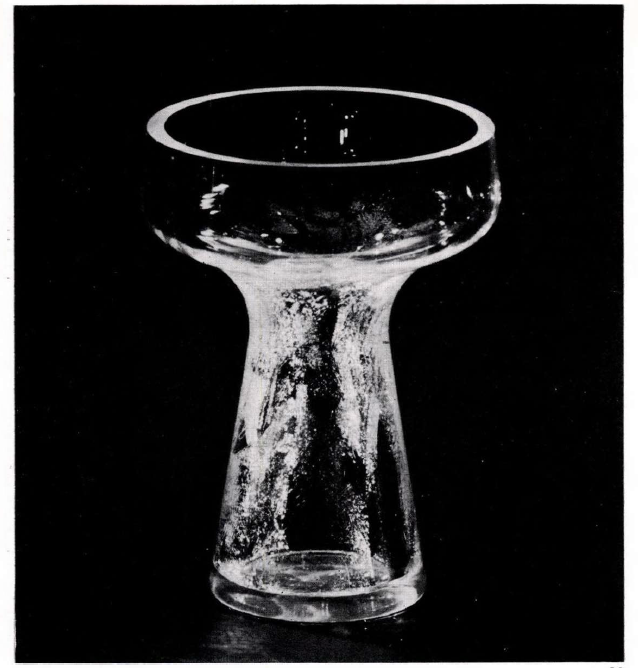

In addition to Zoltán Veress, chemist-designer Zoltán Suha also played an important role in the history of the factory: Suha arrived at the factory in 1957, and co-developed with Veress the so-called cracked glass, amongst others, frequently referred to in the vernacular as “fátyolüveg” (veil glass) – the majority of the decor products of the factory were made using this technique (vases, candlesticks and so on). In the course of said technique, they use several types of glass, which they pour in layers and due to the different thermal properties of the various glass types, the internal layers become cracked – resulting in a spider web-like surface, giving a unique look to the glass object made this way. We came across a product of the kind during our visit to the store of Retrohungary (you can read about it here), and immediately pounced on the object we thought was a chalice at the time.

And now we have arrived to the star of our story, the designer of the Termover heatproof dishes and said veil glass “treasure”: none other but Katalin Suháné Somkuti. Suha Zoltán’s future wife acquired her qualification in the Secondary School of Fine Arts and Applied Arts, and then started working for the Karcag Glass Factory in 1966, where she designed many decorative articles for the company. As revealed by an art catalogue published in 1974, the object we believed was a chalice was in fact intended to be a candlestick („Mai magyar üvegművészet”, 1974).

The big breakthrough was, however, brought by the heatproof dish family designed between 1973 and 1975, implemented as part of the House Factory Kitchen Program, and also represented in the Ceramics and Glass Collection of the Museum of Applied Arts. The dishes debuted at the exhibition titled „A magyar üveg és porcelán a háztartásban” (Hungarian glass and porcelain in the household) in 1975. “…We photographed it at the exhibition of AMFORA Corporation: The Termover egg boiler debuted at the exhibition amidst the heat-proof dishes of the Karcag Glass Factory, which will be available in stores from the second half of the year” („Szép tárgyak háztartásoknak.” (Beautiful objects for the household) Népszabadság, June 8, 1975, p 10)

And so here’s the answer to the question raised at the Artwork Description course: out of the two, deceptively similar objects, one was the egg boiler designed by Wilhelm Wagenfeld in 1933, while the other was the egg boiler designed by Katalin Suháné Somkuti.

The heatproof dish set implemented under the House Factory Kitchen Program and the products of an additional 22 factories were also exhibited at the Budapest International Fair in the fall of 1975: “We must dedicate a few words to the dish set of the Karcag Glass Factory introduced under the name Thermover, made of heatproof glass, seven members of which received the prominent Excellent Goods Forum certification. The house factory kitchen program was called to life by the requirement of creating kitchen culture and bettering the circumstance of dining – as the joint concept of several ministries and the Design Council. The Thermover dishes promote the implementation of this program” (Világgazdaság, November 9, 1978, p 6)

The sets realized in the framework of the House Factory Kitchen Program (baking, cooking, serving pots, lemon squeezer, apple grater, kitchen textiles and many others) were first available in May 1976 in the shopping center of the Kelenföld housing estate, in the store of Vas- és Edénybolt Vállalat (Metalware and Dish Company), but they can also be purchased in the gift store opened as an independent commercial unit of the glass factory in Balatonfüred in the early eighties („Glass from Karcag – in Balatonfüred”, Veszprémi Napló, June 16, 1982, p 4).

Thus, from the second half of the seventies, Hungarian housewives could not only choose from models from the GDR and Czechoslovakia, but from the heatproof glass products of the glass factory in Karcag, too. Some of these might still be found in Hungarian kitchen cupboards, but the questions of which types exactly is something we must find out ourselves.

Literature: Zsófia Rakovszky: Veress Zoltán, a polihisztor üvegművész (2016, MOME, thesis)

Special thanks to: Piroska Novák

Cover photo: Termover heatproof dishes (Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Ceramics and Glass Collection Archive, photo: Benedek Regős)

In our Object Fetish article series, we introduce the emblematic pieces of Hungarian object culture. We go after objects and their designers: we ask questions, we investigate and we learn. A four-hand piece by design theorists Kitti Mayer and Piroska Novák, published every two months.

In partnership with:

Fresh, youthful and exotic momentum | Harlequin Chocolates

Alpine chalet reinvented | Studio Perspektiv