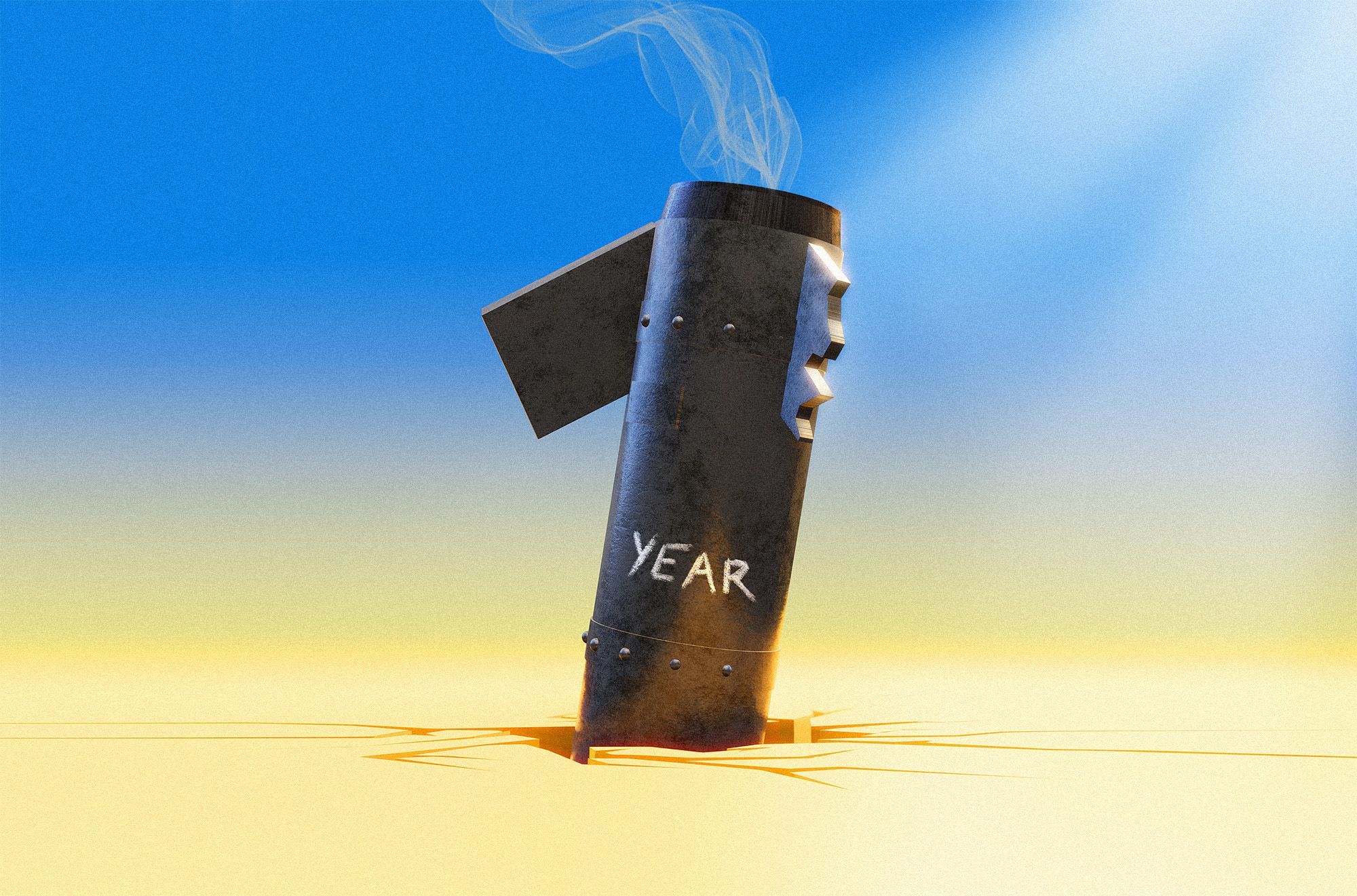

The Russian invasion of Ukraine started a year ago. Thoughts, opportunities, and developments about Ukraine, Russia, international affairs, and the potential of Westlessness.

On Tuesday morning, Russian President Vladimir Putin delivered a speech at the joint session of the lower and upper houses of Russia’s parliament to mark the first anniversary of the Russo-Ukrainian war. Putin’s message in a nutshell: if Russia had not attacked Ukraine, the West would have launched an attack in Donbas sooner or later. That is why, he said, they are fighting the West and not the Ukrainian people. Putin’s view is that the West aims to separate Ukraine from Russia by bleeding it dry. He believes the Ukrainians are the West’s cannon fodder and that foreign powers control the government in Kyiv. Putin also said that Russia would not be the first to use nuclear weapons. Finally, he added that they believe the truth is on their side.

A year ago, at dawn, rockets hit Ukraine as Russia launched a full-scale attack against the country, breaking all the international norms. So, the question arises: what can we write about on the first anniversary of a war? Should we go through the war’s main events and perhaps the most significant successes and failures? Or should we analyze the current plight? It would make little sense as there are too many variables. But we rarely talk about the future and the bigger picture, though these are the ones that really need to be discussed. Vladimir Putin has already summed up his views; it is time for us to do the same.

On the decline of Russian soft power

On 24 February 2022, Vladimir Putin’s army attacked Ukraine because he had exhausted all his soft power instruments to keep the country under Moscow’s hegemony in the Russian sphere of influence. However, Ukraine’s example signals well the decline of Russian soft power in the world, including the post-Soviet states. When the first missile struck Ukraine, all the efforts of Russian propaganda, disinformation, and other soft power tools were eradicated, and the states and communities dependent on Moscow started to distance themselves from the Kremlin permanently.

The Russian-speaking communities in the Baltics have clearly started to shift away from the official Russian narrative. The young people have been completely lost to Russia, and a dramatic shift is also visible in the middle-aged population: In the 2018 Latvian parliamentary election, the pro-Russian Harmony party won nearly 20 percent of the votes, meaning 23 seats, but in the 2022 elections it failed to reach the five percent threshold and lost all its seats in the Latvian parliament. This means a drop of almost 15 percent in four years, and Russian aggression is the main reason behind it. About 45-50 percent of Latvia’s population has Russian roots, leaving the country significantly exposed to Russian soft power. A decade ago, 90 percent of ethnic Russians in Latvia supported Vladimir Putin, while now only ten percent do, and 82 percent of the people in Latvia support Ukraine. These drastic changes show that Moscow lost the support of basically the entire Russian-speaking population of the Baltic states due to the war.

The situation is the same in the other former Soviet Republics. Moscow has lost the Caucasus: Georgia was pushed out of Russia’s sphere of interest by Russian aggression in 2008, while Azerbaijan is sufficiently wealthy and powerful to pursue an independent foreign policy with the support of its main ally, Turkey. As Russia launched the offensive in Ukraine, Azerbaijan escalated the conflict with Armenia, Russia’s last ally in the region, in Nagorno-Karabakh, where Russian peacekeepers operate.

Going further east, the situation is no better in Central Asia. Kazakhstan is Russia’s competitor in the energy market, a politically independent country looking for new, stronger allies in Turkey, Europe, and China. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan also pursue a two-vector foreign policy toward Turkey and China. Honestly, we have not been used to situations such as Tajik President Emomali Rahmon taking nearly seven minutes to list all his grievances to a silent Putin, which happened in October 2022. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan also dropped out of Moscow’s sphere of influence for similar reasons.

Although the Chinese leaders always stress that they see Russia as an ally, in reality, Beijing does not do much for Moscow. A strong, independent Russia is not in China’s interest; Moscow would, at best, play second fiddle on the Eurasian continent in Beijing’s preferred scenario. And India, a long-standing friend of Russia because of arms supplies, aims to switch from this friendship to better Western relations as the West is a better ally against China which they have a border dispute and political conflicts too. Moreover, the power of the Russian-led BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation is an illusion, they will never be able to balance the so-called „Western bloc” as they lack economic strength and there is no sufficient cooperation between its members. These countries are also each other’s rivals on the global stage, and Russia is becoming weaker.

On the so-called Western bloc

Westlessness was the theme of the 2020 Munich Security Conference. According to the Russian narrative, the „Western bloc” is a greedy alliance with hegemony over the world that does not follow even its own rules. The „Western bloc” must face the fact that the world will never forget the shame of Iraq, Libya, or Syria; the attacks, operations, and wars with questionable legitimacy resulted in the death of many people. The concept of Westlessness means a world in which we can do away with this dark past and make the current international order „Westless,” i.e., globally accepted and supported rather than a mere instrument of the so-called „Western bloc.” From its point of view, Moscow is indeed fighting the „Western bloc,” as Vladimir Putin pointed out in his speech, but in reality, the international view on the aggression in Ukraine is much more complex.

Russia is now attacking and destroying the international order signed by the 193 UN member states, so it is not challenging only the „collective West.” Countries that have officially condemned Russia’s aggression include Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina; Somalia, Egypt, Libya, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo; Turkey and Serbia; and Afghanistan, Cambodia, Thailand, and Indonesia. Ukraine is supported with arms or other military equipment by Colombia, Sudan, Morocco, South Korea, Japan, Pakistan, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and North Macedonia, among other countries. So, not just the „Western bloc” stands with Ukraine now, and Russia is not fighting the collective West but the current international order. In Moscow’s preferred world order, where only power politics would limit the imperial, political, economic, or other ambitions of states, the international order would quickly be overturned. Sovereignty and territorial integrity would become empty concepts, and countries would quickly disappear from the map on the altar of power politics. No civilized state wants this at the moment; let me allow to exclude North Korea, Eritrea, and their ilk from this category.

So, this logic implies that the policy of Westlessness should be brought to success in the international community. The powerful, wealthy countries of the „Western bloc” must treat all sovereign states in the world as partners, with respect, humility, and friendship, working for a jointly defined international order and the peace that it maintains, with each country by its own means. Finally, the West must recognize its past mistakes and remedy their impact on the present. Although the „Western bloc’s” global economic power is declining, and the world’s center of economic gravity is shifting eastwards, we should not forget that East Asia also supports the values that underpin the international order; therefore, these countries are the natural allies of the West. The policy of Westlessness will require sacrifices, but it must succeed.

On an emerging Ukraine

The first missile that hit Kyiv eliminated not only the Russian soft power but also created the permanent unity of the Ukrainian nation. We should be in no doubt: the Russian „liberators” only brought destruction and suffering to eastern Ukraine, razing Russian-speaking cities and towns to the ground, displacing the population, and making Ukrainians from those who did not consider themselves Ukrainian before the war by eradicating the last seeds of pro-Russian attitude. This has led to a social psychosis uniting the Ukrainian nation, which turns towards the occupiers with absolute hatred. But the question is to what extent this psychosis will hinder Ukraine when a real stalemate or Russian dominance develops, and they will be forced to negotiate.

People are now getting to know Ukraine. They are learning about Ukraine’s history and the social and economic developments that have shaped this area over the centuries. Ukraine has history and heritage, but the modern concept of nationhood has only just been born. And, as with any nascent nation, there are teething troubles: nationalist extremism, chauvinism, and emotional overheating. And these are exacerbated by the horrors of the war. Showing patience and a willingness to compromise is the most important from our side regarding the emerging Ukrainian nation-state, but the Ukrainian side can be expected to do the same.

Undoubtedly, Ukraine has not been a great place to live in the past three decades. The country’s 51.5 million people population dropped to 43 million by 2021; the main reasons behind this are low living standards, poor public services, pervasive corruption, lack of prospects in general, decentralized governance with strong local oligarchs, massive Russian influence, and the inadequate public healthcare system. Ukraine has a population of 36 million now, including those roughly 3-6 million people who live in the currently occupied territories. Rebuilding Ukraine once the conflict is over will be an extremely challenging task, as it will not be possible until Kyiv has adequate security guarantees to ensure the safety of international investors. Substantial changes are also needed in Ukraine’s legal system to fulfill the criteria of Europe’s rule of law standards. Ukraine’s potential Euro-Atlantic integration would be an even more difficult task; it is not even sure whether it can finally happen. In this regard, NATO and EU leaders should refrain from hasty statements because they would raise the expectations of Ukrainians too high, and the slow integration processes could quickly create frustration and anger in Ukrainian society. To be realistic, we must acknowledge that we talk about decades-long processes. We do our best if we do not keep quiet about this.

On Russia and false equality

Russia is undoubtedly in a difficult situation. Its role as a major world power needs to be differentiated: Economically, Russia is considered a regional power maximum, which has become completely isolated in terms of economic and political influence in both Europe and Asia. Its former status as a great power is maintained by its permanent membership in the UN Security Council and its nuclear arsenal. Russia is experiencing the largest tragedy in its history; the Russian people are destined for much more than what their current political leadership provides.

Russian society suffers enormous losses in the war. The nine years long Soviet-Afghan War’s 26,000 killed and 54,000 wounded soldiers extremely shocked Russian public opinion, and now, in a single year, Vladimir Putin’s war has left 145,000 dead and 435,000 wounded. According to some military experts, there might be even higher losses on the Ukrainian side. The devastation is incomprehensible.

The nearly one million people who fight or already have been wounded or killed on the front lines, or maybe became prisoners of war in Ukraine, are a segment of aging Russian society whose loss will have unforeseeable consequences for Russia’s future. They are all healthy, able-bodied men of working age, of which there were not enough in Russia before the war either, and since the mobilization started, there are even fewer and fewer. In less than a month after the announcement of the mobilization in September 2022, 700,000 men left Russia, and this number is still steadily increasing. According to some Russian economists, the mobilization itself has more severe consequences for the Russian economy than all the international sanctions. And speaking of sanctions, they are slowly starting to work; it is no coincidence that the Russian leadership is becoming extremely stressed. (A fuller discussion of the sanctions would take a whole essay, though.) They can indeed not stop the war. However, contrary to the hasty and foolish statements of some politicians, they are effectively pushing Russia back decades in terms of economic development and prospects, isolating Moscow internationally, both from market investors and the capability to make international agreements. An economically vulnerable, weak Russia is also in the interests of its closest allies, who can hardly be called friends since their prosperity is based on an asymmetric dependency. (Yes, we can wink at China and India here).

Another key point of the Russian political leadership and dominant ideology is a kind of juxtaposition whereby they try to portray Russia as an equal partner in the international community, demanding a place. Moscow highlights the shameful interventions of the West in Iraq, Libya, and Syria, to justify its own unjust and illegitimate war against Ukraine. This juxtaposition, this fairy tale of equal countries and nations, might even suggest a willingness to compromise, but we should not be deceived: Russia is pursuing an absolutely imperialist foreign policy. Advocating for equality is only in Moscow’s interest until it is not sufficiently strengthened to subordinate its partner, just as it has done in the post-Soviet region, in the Russian Far East, or with the ethnic minorities living in the territory of the Russian Federation.

But we should not close all doors. The opportunity to communicate must be given even though there is no doubt that most of Russian society supports the „special military operation.” Russian citizens became involved in the war by acting as supporters due to the all-encompassing propaganda and total state control. Still, we should not completely exclude the Russians from the international community as permanent stigmatization and ostracism would mean the indirect victory of Vladimir Putin’s narrative. In 1814, during the Napoleonic Wars, 100 Russian soldiers marched into the French capital after the Battle of Paris, experiencing a tiny bit of Western society, politics, culture, and economy. And in 1825, these same soldiers and their circles rose up against the Tsarist rule in the Decembrist Revolt. We should keep this in mind.

This opinion piece does not reflect the general opinion of the Hype&Hyper editorial team.

Graphics: László Bárdos

Exhibition launched of the finalists of the most important Czech design competition

Reserved launches its first home furnishing collection