From the color and texture of the food on our plates to the network of traditions and habits encoded in us as well as personal preferences, there are several factors that influence our sense of taste and relationship with food. Edibles possess features that open new avenues for better systematic understanding and the planning of our diet.

We understand the multisensory nature of food from a very young age. When infants start to explore the world with their five senses, food is usually their primary source of experience. Holding a slice of a cut-up apple in their hands, with their fingers, they can feel the shape and the firmness of the flesh of the fruit, while with their eyes, they are able to see and differentiate between colors of the inside and outer layer of the apple and taste the slightly sour or deliciously sweet flavor and after a while, even hear the sound of their own chewing. When our brain is stimulated, it starts processing and synthesizing unfamiliar experiences and connecting them to familiar ones or turning them into brand new knowledge. This is how we learn throughout our evolution as well: if something tastes bad or looks uninviting, it is potentially toxic or harmful, therefore our brains suggest we avoid it.

For a long time, food science has been researching the molecules that make up our dishes. However, until now, this research was mostly done on the level of macro and micronutrients. Molecular gastronomy—a term coined by Hungarian-born British physicist Miklós Kürti and French chemist Hervé This in 1988—was perhaps the first field that dug deeper in the field. Interestingly, a decade earlier, Marie-Antoine Carême had already invited science into cooking the perfect stock realizing the importance of the invisible ingredients while also listing the five French mother sauces: basic white sauce or béchamel, (beef, chicken or fish) stock-based veloutés, brown sauce, aka. espagnole, classic tomato sauce and butter-based sauces such as Hollandaise later perfected by Auguste Escoffier. Today, many renowned chefs like Heston Blumenthal, Grant Achatz or Ferran Adrià are experimenting in this field, wowing their restaurant guests with innovative dishes that play with the textures, shapes and compounds.

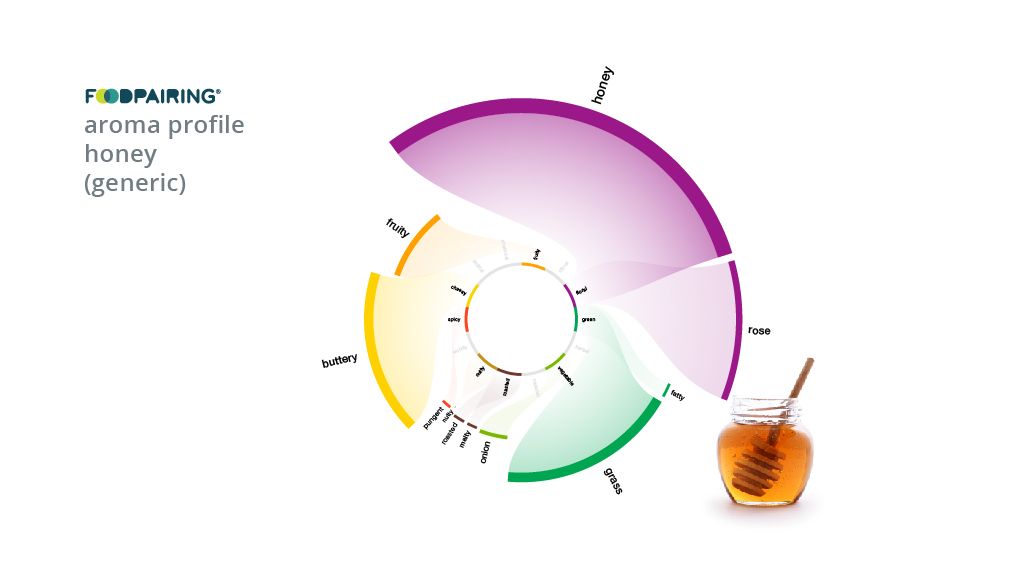

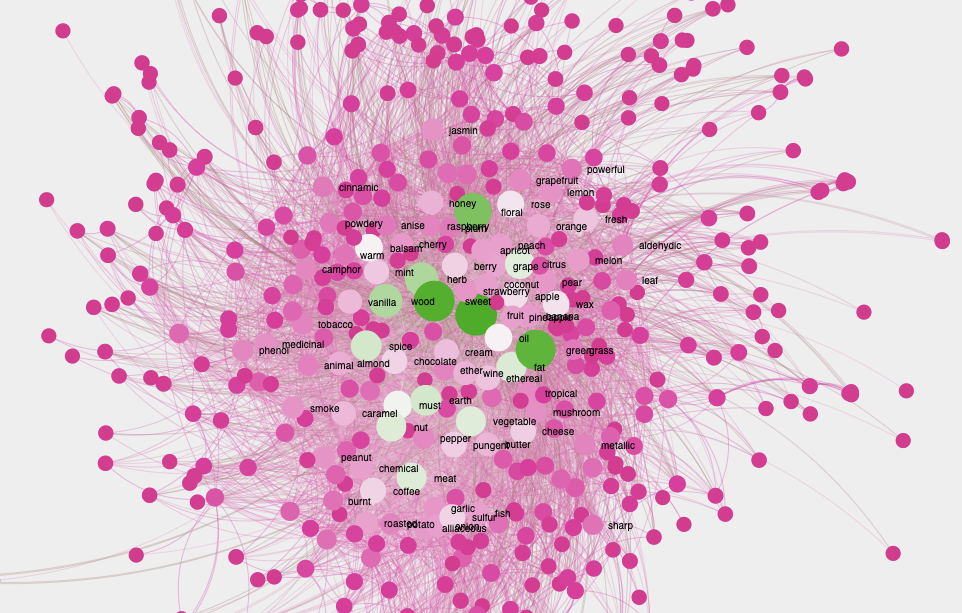

But how is flavor structured? Surprisingly, only one fifth of flavor depends on our taste receptors. The remaining eighty percent is made up by the aroma compounds we perceive with our noses. This is how taste and fragrance together are responsible for flavor. Each ingredient has a specific aroma profile that can be categorized as for example, flowery, fruity or herby. If you are interested in what pairs well with what ingredient, you need to be on the lookout for common notes. According to the hypothesis of “food pairing”, ingredients that share the same main molecules go best together. The term was first used back in 1992 when Blumenthal became intrigued by why certain food pairs like caviar and white chocolate or vanilla and tomato taste better together than others. He asked perfume-maker and food scientist François Benzi to help him out: the two of them broke the ingredients down to molecules and discovered the similarity lies in their aroma compounds. The more than ten thousand aromas—strawberry in itself boasts more than four hundred—provide endless opportunities for experimentation in the world of molecular gastronomy.

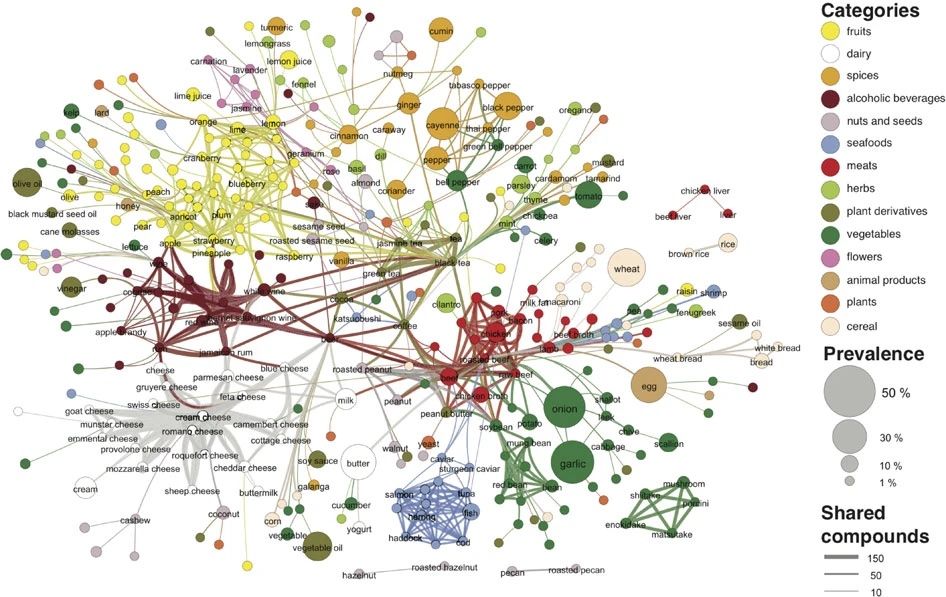

Internationally acclaimed network scientist Albert-László Barabási goes even further. His research first published in Nature Magazine claims that there are more than 20,000 biochemicals present in the “dark weight” of our food. BarbásiLab analyzed 1,201 flavor compounds of 381 ingredients and more than 56,000 recipes to draw the flavor network model that illustrates their relationship in an expressive way. Each node on the map corresponds to an ingredient, the color of the node indicates its type while its size tells you how many recipes contain that particular ingredient. The nodes are connected if they share the same flavor compounds. The research findings also shed light on the way these compounds behave and affect the health of our bodies. Today, in the world of “ultra-processed foods” our diet rarely includes natural ingredients like the ones found in the Mediterranean diet. Comfort products might satisfy our taste buds, but they are neither good for our bodies nor sustainable and we should explore why they are more attractive than going back to our healthy “food roots”. Therefore, we should aim to find compound combinations that are both satisfying to our senses and our bodies.

Flavor compounds also invite us to travel around the world. When looking deeper into the harmony of flavors, we are usually faced with cultural differences: European cuisines traditionally pair and build on ingredients with similar molecules, while contrasting flavors are the basis of Asian gastronomy. This tells us an exciting story about how our taste developed globally and helps us in designing dishes that could turn our attention from processed foods back to better, natural alternatives. These connections also highlight the similarities in our own and other cultures’ cuisines. For example, many regions share recipes of meat cooked in a spicy ragout with vegetables. A Persian spicy-saucy dish of lamb, aubergine and tomatoes called khoresh bademjan or Haitian legim made of vegetables and cooked beef and served over rice are both highly similar to Hungarian pörkölt. Even though dishes are adapted to local ingredients and other determining factors like religion and climate, they still share a lot of resemblances..

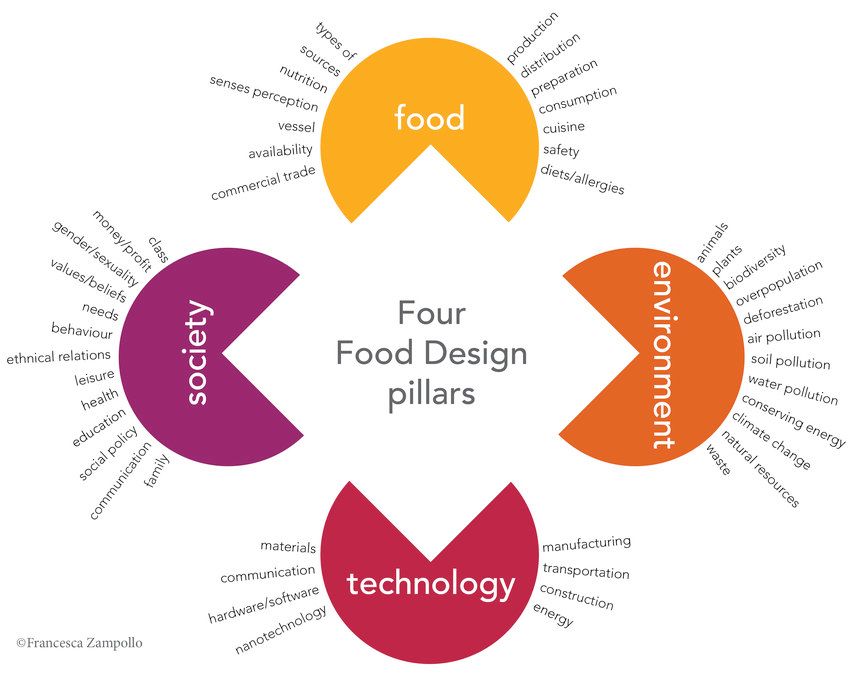

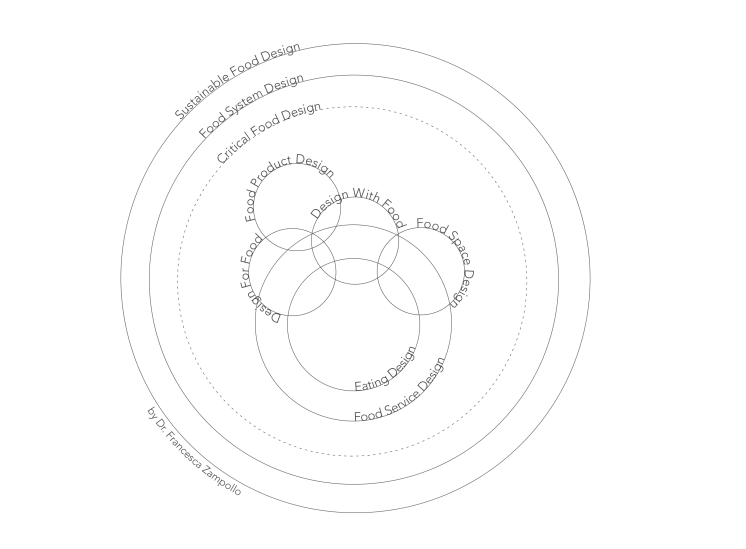

Networks connecting edibles go beyond the perception of taste. A whole new spectrum unfolds in front of us if we accept that there are no real boundaries separating gastronomy, design and science. When looking more closely into, for example, the terminology of food design, we realize that the subcategories are not clearly distinguished but also form a kind of network. The founder of International Food Design Society, Dr. Francesca Zampollo tried to create a more precise distinction of these categories by conducting rigorous research and individual interviews. First, she defined four determining factors to help her design the system: environment, technology, society and food.

Besides the main categories, she distinguished the following subcategories: 1. Design with Food 2. Design for Food 3. Interior Design for Food 4. Food Product Design 5. Design about Food 6. Eating Design. These subcategories create a diverse portfolio of products and services. Design with Food experiments with food as a raw ingredient usually to radically alter its shape, texture and flavor (as, for example, in molecular gastronomy). Design for Food means all the objects that help shape or store food. This includes everything from the iconic Coca-Cola bottle or the Alessi tea kettle designed by Michael Graves to everyday objects like a Nespresso coffee maker or the packaging of a Milka chocolate bar. These objects go beyond being ordinary tools and packages since they also serve as channels of communication for the brand and their product.

Interior Design for Food concerns the spaces where people eat or make food. Even though the end product is not edible, the category’s ties to food are obvious: creating the perfect atmosphere, lighting or even color palette can enhance the food experience while creative usage of space tells a story about the values and spirit of the place. Food Product Design is the design of mass-produced food products in which clearly distinguishable shapes are used to denote the brand identity. Most products found in supermarkets are designed products and therefore part of this category. Design about Food is a peripheral category including objects using food as an inspiration not as a tangible matter mostly in a humorous or satirical way.

Eating Design is perhaps the most important among all the categories dealing with the activity of eating, examining and designing projects about the interaction between food and people. As food serves first and foremost as sustenance for most consumers, it can be interpreted through our reactions. More and more exemplary local and international experts of eating design are challenging these boundaries to experiment and redefine our relationship to eating. These categories overlap in many aspects and are part of the entirety of how we think about and perceive food on the conscious and subconscious levels.

Whether we’re having a pleasant or unpleasant food experience, there are several different factors that influence our perception. Today, we can even design our very own flavor ID to understand why we are drawn to or reject certain flavors. It’s important to explore the exciting world of food and as Blumenthal once said “question everything” so we can find the key to a joyful and healthy diet while understanding the world that surrounds us more deeply.

Source: Portfolio, Food&Wine, Network blog, Nature, KtchRebel, FoodPairing, Food52, SóBors, 196 flavors

Cover photo: Melbourne & Cheese

Communicating with objects—interview with ceramic designer Anett Sáfrán