People, words, buildings, stories, and moods—all of these and more have contributed to creating the Budapest we know today over the past 150 years. To mark the anniversary, we asked people who are connected to the capital by a thousand (or at least a hundred and fifty) threads about the past and future of Budapest and their personal connection to the city.

Vilmos Kondor, author

What would you have been in Budapest 150 years ago?

A messed up, unscrupulous lawyer. It took me a while to understand the question: what I would have been. At first, I read it as what I would have liked to have been, and I was about to imagine myself in heroic and exciting roles, but the question was in the end, what I would have been. Well, maybe not a shyster, but a decent university graduate, but I would not have been mentioned in the Pesti Napló (a former Hungarian political newspaper—the Transl.) as a champion of courtrooms, and László Kun certainly would not have included me in his book A magyar ügyvédség története (The History of Hungarian Lawyers—the Transl.). Between two trials, I would have been a regular libertine in the market stalls along Andrássy Avenue, wooing scantily clad, coquettish French acrobat girls.

The differences in geography, history and development still create tangible contrasts between Buda and Pest. What do you like about both?

In Pest that it’s not Buda, and in Buda that it’s not Pest. It’s hard for me to forget the historical Pest that I write about, so for me, Buda still equals the Tabán, even if it’s no longer that way. I love the ideal of Buda, perhaps the proudly worn, now mostly gray remnants of its former glamorous atmosphere. The little streets running up to the Castle, the flowers hanging side by side from the balcony railing, and the worn-out terry towels. In Pest, it’s easier for me to love the past and the present, because the way the part of the city that is close to my heart looks today—the sixth, seventh, and eighth districts—could easily serve as the basis for a photo album about the 1930s.

What are the best and worst things about Budapest?

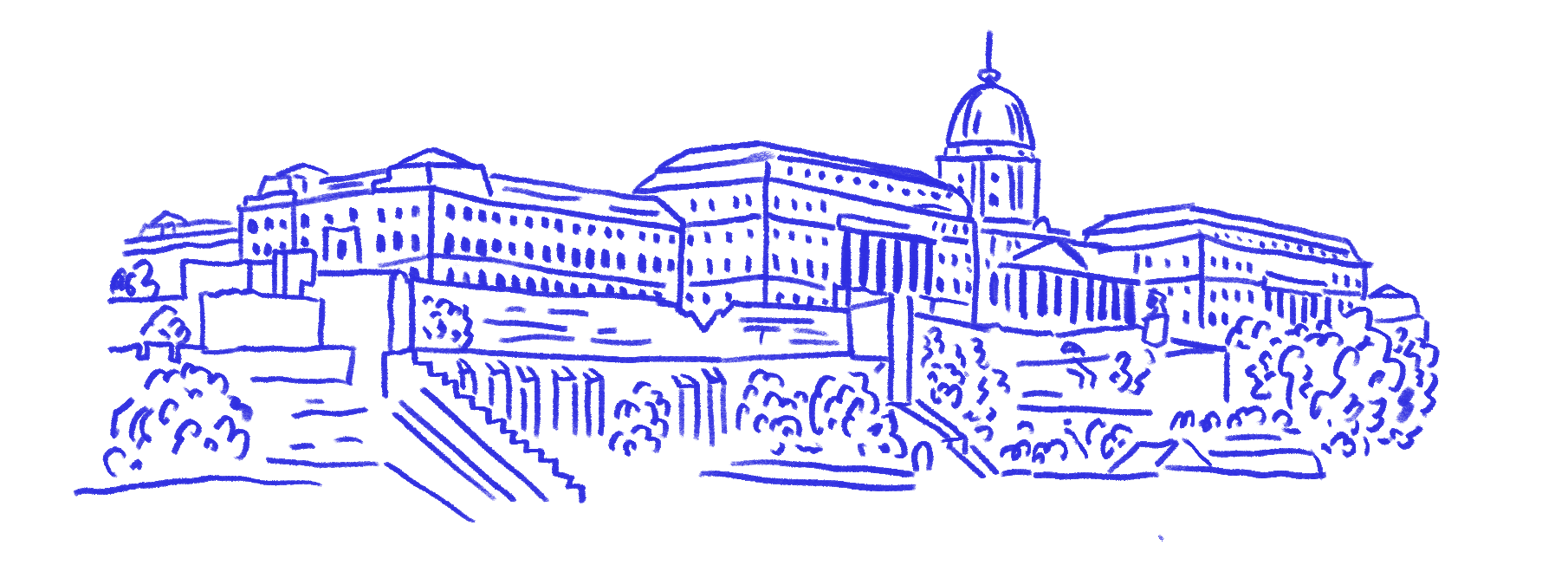

The best thing is that it has the qualities that very few cities have, with the river, the hills, the boulevard, the Castle, and the whole whatnot resulting from its geographical location. And the worst thing is that not only do we not take advantage of these assets, but we downright degrade them. With a little—well, now a lot—of attention, Pest could be a better and more beautiful city than Vienna.

Which image and/or song best describes Budapest for you?

Pesti polgár (Citizen of Pest—the Transl.) performed by Dóri Behumi. This is number one for me. The lyrics were written by Jenő Rejtő, and just these few verses would have been enough for eternity. The other one is Az én városom (My City—the Transl.) by Zorán. Dusán (Zorán’s brother, who wrote the lyrics—the Transl.) is one of the city’s most important poets. As for images, any painting by Antal Berkes brings me the Budapest I love so much, and of course, Ernő Zórád’s drawings, especially the wonderful Tabán series.

If you had to recommend a book about Budapest that might also be available in a foreign language, which would it be?

Escape to Life or Happy Generation by Ferenc Körmendi, both published in almost a dozen languages from English to Danish, to German, to French.

Who or what is the most ‘Budapester’ person or thing for you?

Sándor Nádas. He was the chronicler of Budapest for over 30 years, until 1939. It was not his intention, nor could it have been, but the thirty years of the Pesti Futár (a former Hungarian political journal—the Transl.) are like a great novel of a great city. A wonderful reading, and an amazing achievement. Each word is golden.

If you had to live in one of the region’s other capitals instead of Budapest—Vienna, Belgrade, Ljubljana, Bratislava, Prague, Warsaw, or Zagreb—, which one would you choose?

In Venice, which is not a capital, but at least it’s nearby. Venice, by all means. I am deeply drawn to its architecture, history, mysticism, legend—and the idea behind the city. It’s as big as it gets. You couldn’t build more houses there, not even taller ones. Anyone who wanted to live there had to learn to live with the others, or else they left. There was no middle ground. And more people came than left, which is telling not only about the city but also about us, its potential residents.

How do you see Budapest in another 150 years?

Shall we dream then? Or, sticking to reality, shall we picture nightmares? What I imagine is one thing, what becomes of it is another. Ultimately, it’s all the same, because a city without its inhabitants is but an empty shell, and the inhabitants of Budapest have been getting slapped in the face for about 150 years, and they have been taking them like a champion. The city could become a modern miracle, with beautifully preserved and cherished historic districts, a quiet and elegant business quarter, and green and liveable suburbs. But it could also be that steel towers will rise over the wretched, shabby, dusty downtown, and all the old houses will be torn down because only the new can be good, and the downtown ghetto will be ticketed because a few thousand people will decide they are not going anywhere, let them all drop dead.

Whatever. The same indestructible easy-going cheerfulness pulses in the Budapester of 150 years ago, now, and 150 years from now, and I’m sure they’ll be laughing at pretty much the same jokes, albeit with different characters. It’s a pretty young capital, but it’s also one of the most gritty. As long as the people of Budapest exist, there will be a city, and they will shape it as they wish—even if it’s not obvious from the outside.

Portrait: Vilmos Kondor

Graphic design: Roland Molnár

A constructive coexistence that needs to transform