James A. Kapaló’s research has primarily focused on the history and experience of religious and ethnic minorities in Central and Eastern Europe. He works ethnographically with communities, archives and museum collections to explore vernacular knowledge, religious practices and local memory. He was also one of the editors of the book The Secret Police and the Religious Underground in Communist and Post-Communist Eastern Europe, which was published in 2022 by Routledge. We asked him how he started to deal with Eastern Europe and religions; what is the religious underground; how the secret police and religious communities tried to outsmart each other; and why is it important to deal with our past.

Your research primarily focuses on the history of religious and ethnic minorities and State Security in Central and Eastern Europe. How did you become interested in the region and in these topics?

My mother is from England and my father is from Hungary, so I’m actually a second-generation Hungarian from the UK who has lived and worked in Ireland for the past fourteen years. My father’s family comes from the Eastern part of Hungary, the family is Greek Catholic with some Ruthenian or Ukrainian connections, and my grandmother also spoke Slovakian. My father also had an encounter with the State Security as a young man and was actually imprisoned for trying to leave Hungary in 1955. However, it was during the 1980s I started to travel back to Hungary with him and I became interested in the history and fate of Hungary and the neighboring countries. In the early 1990s, after the Revolution in Romania, I moved to Csíkszereda and I taught there for nearly two and a half years. At that time I became absolutely fascinated with questions of religion and identity. The upswing in interest in religion in the formerly communist countries that I experienced in Hungary and Romania, mixed with my own family’s history and background all came together in the research that I do, which connects Central and Eastern Europe, religious diversity, and State Security or the secret police.

Amongst others You wrote about the Moldavian Csángó identity, You were amongst the Gagauz in Moldova, and You studied Inochentism in Moldova and Romania. How did You find these topics and communities? What is your research method?

I started off my apprenticeship as an ethnographer when I was living in Csikszereda. Vilmos Tánczos, now a good friend and colleague of over 30 years, took me on some field research trips to Hungarian villages. After I came back I did a master’s degree at the School of Eastern European Slavonic Studies. I got to know the Csángó, which is a Hungarian community in an Orthodox environment, and their identity is associated with Catholicism. My interest in them goes on even to this day, but I didn’t publish about them, because it became very emotive for me. Instead, I wrote about the Gagauz, a Turkish-speaking Christian community in Moldova. Since they speak Turkish, somehow they’re connected to Islam and Turkey, but they are actually Orthodox Christians. These two cases open up all sorts of questions about identity and belonging. What is the essence of ethnic identity? What is the role of religious identity in ethnicity? Where do ideas of national identity come from and how are they formed? However, later I moved from mainly ethnographic research and started to focus on archives and the role of the state of the transformation of those identities in the Communist era.

You edited the book The Secret Police and the Religious Underground in Communist and Post-Communist Eastern Europe together with Kinga Povedák. How was this book born?

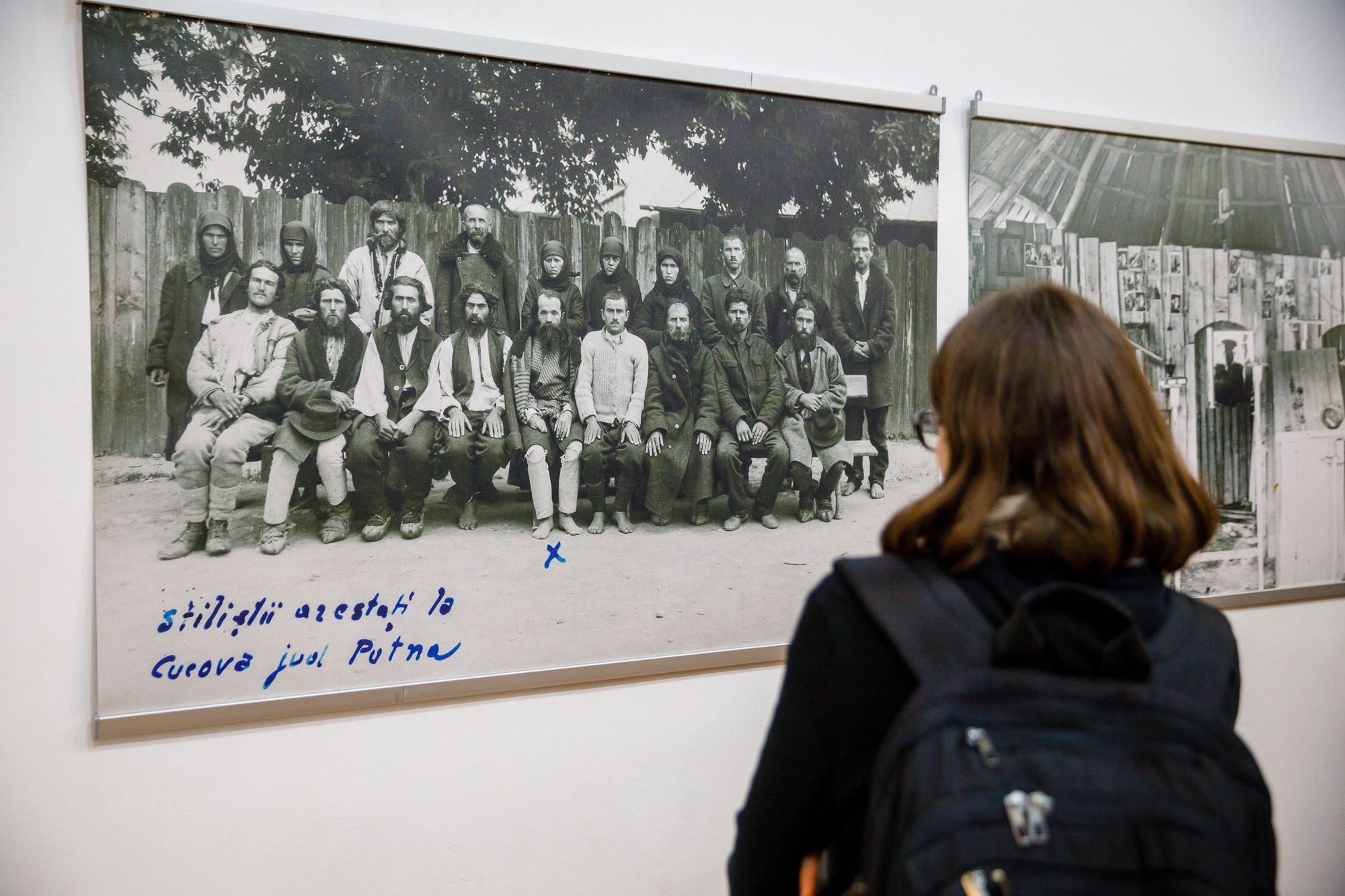

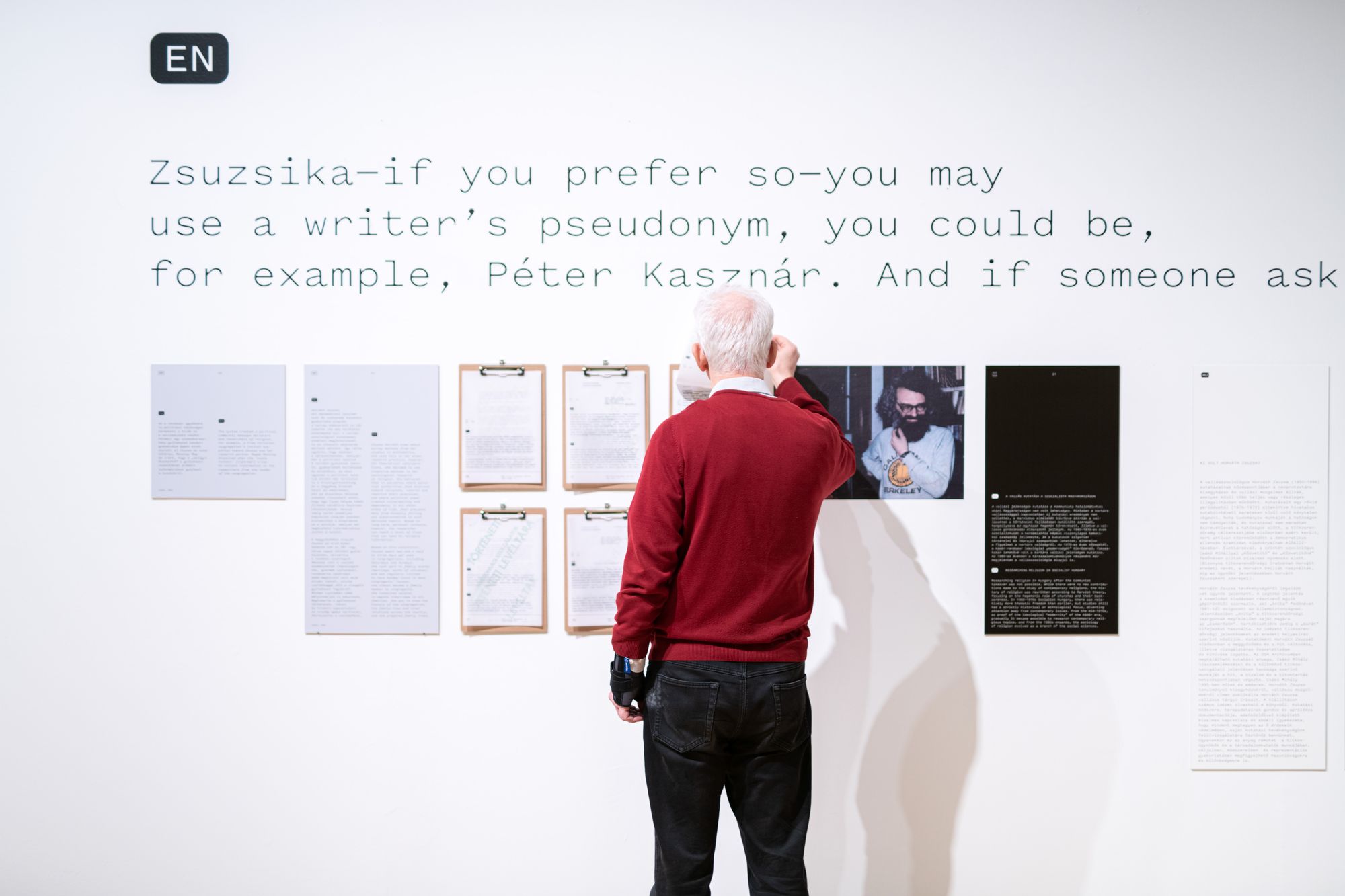

From 2016 I led a European Research Council project called Hidden Galleries, which re-examined and re-contextualized the holdings of secret police archives in Romania, the Republic of Moldova, and Hungary, and I received funding for four years to put together a team. We had a fantastic collaboration with the Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security, who hosted the very first workshop of the project. We invited other collaborators from the Czech Republic, Poland, Lithuania, and the former Yugoslavia. I wanted to bring together scholars who could really look at the experience of communism and its relationship to the transformation of the religious landscape, that’s why we attempted to make it both interdisciplinary and comparative. We also used a kind of grassroots approach which required us to work with the archives in a way that they’re not designed to be used. The State Security archives were never intended for researchers to come along one day and look at them. They were conceived as something that would be entirely closed, that even members of the Communist Party wouldn't be able to get to. We wanted to look at the materiality of those communities targeted by the state in terms of their ability to produce and reproduce their religious culture, and their visual cultures, even under intense pressure from the communist state. Perhaps paradoxically, the secret police archives contain rich collections of the patrimony of religious groups, many religious items, photographs, and publications confiscated by the state. We used many of these materials in a series of exhibitions we curated for the public in Romania, Hungary, and Ireland. This was an important part of the project’s aims, to take or research to a wider audience and begin a societal conversation about the legacy of the secret police operations and the patrimony that remains hidden in the archives.

Could you define briefly what is religious underground?

The term ‘religious underground’ emerged as a key motif during the Cold War. As early as the 1920s the term was already in use to define the dark, dangerous activity of religious groups in the Soviet Union. Later, Radio Free Europe also used it, but as a place of courage and resistance. The sides used it as a metaphor, and it became a reality through the actions of the State Security, through samizdat publications, and through the works of dissidents in the West. However, it's not simply a metaphor or a construction. The underground was also a lived reality in many cases, people lived their lives in the underground, either literally or metaphorically, and they performed it with their bodies and activities.

The secret police had to or wanted to know everything about their target group. How did they manage to get the knowledge and did they have misunderstandings or make mistakes?

The secret police usually tried to infiltrate groups by recruiting informers or planting agents in religious communities. The informers were in many cases actually well embedded within these communities, they had an awful lot of insider knowledge, and they knew intimately the beliefs, the rituals, the prayers, how the community operated, the connections, and even how money was exchanged. They could report very accurately and very well on the religious life of the community, but not all informers did this willingly, many would withhold information or give a lot of worthless information so as not to harm their friends and fellow believers. In terms of theological (mis)understandings, there is one example from Hungary. In one of the chapters in our book by Éva Petrás, there is a photograph of a group of Jehova’s Witnesses at Lake Balaton. The agent who followed them said that they just made an excursion there. He failed to pick up on the fact that what he had seen was actually a communal baptism ceremony.

In what ways did the secret police change the way the religious underground worked? They probably knew that they could be surveillanced.

Of course, religious communities were often aware that they had been infiltrated or potentially were being surveilled and they took actions to compensate for that or to protect themselves from the negative consequences. In the book, I write about a group of Inochentists in Romania who knew about the activities of the state and devised a spiritual weapon against them. They gathered food, which was blessed by their spiritual father, and then the community intentionally gave it to the wives of officers and members of the state bureaucracy and in this way, they secretly fed them with blessed food to protect the community. Tatiana Vagramenko has written about Jehova’s Witnesses in Ukraine, who basically told their own members to become informers so that they could infiltrate in reverse the State Security system. These are very complex phenomena, which demonstrate that the simplistic ‘oppressors versus heroic resistors’ narrative doesn’t work well.

How did the secret police try to interpret the religious activities as a threat to the state?

The state defines what is legal and illegal, what is within the bounds of the law, and what is outside of it. In this sense, the activities of churches were often genuinely outside of the law, their members were breaking the laws of the state, and they were doing it knowingly and intentionally. Anyway, it was much easier to convict members of religious communities for economic crimes than for political ones. Many of the operations were directed against the tangible, visible, and material aspects of religion. For example, a priest in Hungary was generating money for himself and his parish by selling candles. The State Security file said that he would travel to Budapest, buy the candles for one forint and come back, bless them and sell them for ten forints in the village. What the State Security did, as far as I can see from reading the files, was plant photographs of Mindszenty into the boxes that contained the candles and then ‘discover them’ and accuse him of anti-state activity for supporting the cult of Mindszenty. The priest was threatened with five years in prison if he wouldn’t become an informer. Later, it seems, he quite liked the idea that he had this special role, or at least that’s the way the State Security presented him. He was handling it in a romantic kind of way, enjoying the special status.

You have been writing about these topics for decades. Why do we have to deal so much with our past?

Each of the Post-communist societies dealt with the past or attempted to deal with the past in different ways. What we see today is a failure to fully deal with the issues and consequences of the past. In the context of the war in Ukraine, we see an intention to rapidly rewrite, recontextualize, and redefine what that past means. But it becomes very clear to me that we are entering a phase in the history of Europe when more than ever we have to learn from our past. It may sound like scholars harp on about the same things over and over again, but amnesia is very quick to take hold and that leaves people victim to influences in the rapidly transforming landscape of news and social media. The way that we lead our lives, we are losing a sense of our shared past very quickly. That’s what I learned about history in relation to memory and how it’s incumbent on all of us to speak out and challenge falsehoods as they emerge. I think as academics we really need to turn our attention to that.

The Secret Police and the Religious Underground in Communist and Post-Communist Eastern Europe (ed. James A. Kapaló, Kinga Povedák)

Routledge, 2022

Hidden Galleries project

Photos: Andrea Bényi / Milán Rácmolnár /Roland Váczi

In our Printed Pasts series, we focus on the past and the recent past of the Central Eastern European region through recently published books of different genres.

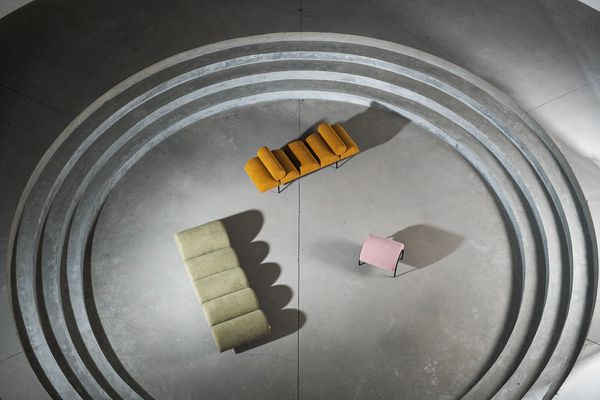

Furniture that tell a story: introducing NORNA

Gold medal for the Museum of Ethnography’s Motif Creator app