How does the presence of ports and ships shape the history of a city? Why is it worth returning a piece of the past to the present? What values can a preserved steamship, more than a hundred years old, bring to the fore? Behold the Kossuth Museum Ship—an entry in the city diary by Gábor Zsigmond, Deputy General Director of the Museum of Transport.

In our latest series of articles celebrating the 150th anniversary of Budapest, we explore the city’s various layers, that have overlapped or overwritten each other time and time again. We present urban structures, public landmarks, and details that have shaped the Budapest landscape. Mosaics of urban history in the intersection of a topic, an expert, and a site. Part one!

In the heart of the city center, surrounded by the World Heritage panorama of the Buda Castle, the Kossuth Museum Ship is moored at one of Budapest’s oldest boat stations, on the Pest side of the Chain Bridge, where it has been docked since 1984. As Gábor Zsigmond has pointed out, the ship has become such an integral part of the Pest quay and the cityscape that it is almost like air: although there is a good chance that we may have passed it several times, we would only notice it when it was gone.

Transport as a defining feature of the cityscape

Gábor Zsigmond has two main passions—or, as he puts it, “obsessions”: one is Budapest and the other is boating. In the course of his professional career, he works at the intersection of these two or in a related field. He is a historian by training but, being interested in economic and transport history, he quickly decided to specialize in this direction. As he explains, he has no childhood memories of being a fan of vehicles—his love of transport developed organically during his university years. Although his main interest was in boating, he added: “It was followed by trams, Ikarus buses (Ikarus being a former Hungarian bus manufacturer—the Transl.), and practically all branches of transport.” Gábor has been Deputy General Director of the Hungarian Museum of Science, Technology and Transport since 2016, and before that, he worked for Budapest’s public transport operator, BKV. Here he was in charge of the Urban Public Transport Museum of Szentendre and the Millenium Underground Museum on Deák Square in Budapest, and also helped to establish the nostalgia transport routes in Budapest. He adds that this was also the time when many of Budapest’s historic public transport developments took place, such as the launch of the Metro Line 4 project, the introduction of the red and white colors of the Metro Line 2 underpasses, and the arrival of 150 new articulated Volvo buses and 40 new Combino trams. “We don’t even think about it, but many of the defining elements of Budapest’s street or cityscape are related to public transport: the yellow of the Budapest trams, for example, is certainly one of them,” he says. “What I find most interesting about transport is what it tells us about the people who lived in the social and economic context of the time,” Gábor explains.

A symbol of the connection between Budapest and the Danube

Gábor’s passion for ships and boating is not strictly technical or technological, but rather inspired by its cultural and social impact. “The beauty of boating or water transport is that it transports not only passengers or goods but also ideologies and ideas,” he continues. “For me, this is what makes a waterfront city more exciting and diverse. I am convinced that Budapest would not be such a city if there were no ships on the Danube,” he says. The history of Budapest is a good illustration of the impact of ships on the city’s development: they brought news from Vienna and Bratislava, and the first information points and cafés were set up on the banks of the Danube. The first omnibus, the ancestor of the motor bus and the trolley bus, connected two cafés between the Danube bank and Városliget.

The Kossuth Museum Ship, as it is known today, also plays an important role. As well as being a surviving relic of the “Happy Peacetime” (commonly denoting the first 14 years of the 20th century—the Transl.), it is also one of the oldest steamships on the Danube: its presence is important because no other steamship of its type has been preserved for museum purposes. As Gábor explains, the Kossuth Museum Ship was built before the First World War, in 1913, when it was named the Ferencz Ferdinánd Főherczeg (“Franz Ferdinand Archduke”) and could accommodate more than a thousand passengers. The steamship operated to Mohács and Esztergom with the primary task of transporting various fruit and vegetable goods to Budapest together with the fair-bound costermongers. “If you think about it, this in itself is a very nice symbiosis. How much work do we do today to be able to consume farm produce and organic vegetables? And this ship used to go to Mohács, passing through some of the ports in the Alföld so that people could unload their bags and sacks on the quays in Budapest. Today the quay in Pest is a four-lane motorway, but there used to be markets where servants would buy fresh chickens, geese, or fruit and take it to the homes of the citizens of Pest, where lunch would be ready by midday. This was the way it went day after day, and this ship was an integral part of the normality that I think we still long for today,” he explains. Of course, it is also important to note that the Kossuth ship can thus be seen as a symbol of the vital link between the city and the Danube, which is becoming increasingly difficult to achieve today because of the car traffic on the quay.

Gábor adds, that althought it may seem strange from today’s perspective, but at the time the Kossuth steamship was built, Budapest was practically a shipbuilding center. “There were several shipyards in Óbuda and Újpest. Until the 1990s, strange as it may seem, more than two hundred seagoing ships were built here, so not just river ships. In fact, Budapest has a long history of shipping and shipbuilding, and the Kossuth steamship is one of the relics of this old, traditional shipbuilding,” he notes. One of the characteristic structural elements of the ship was actually developed at the Újpest Shipyard: “The bridges on the Budapest stretch of the Danube were already in place at that time, so the ship had to be adapted to this. A very exciting solution to this challenge was found: the funnel of the ship retracted when it went under the bridges. That is why we can still see the inclined funnel today,” explains Gábor.

The steamer has changed names and owners over the years. It was given its present name in 1953 and continued on its regular route until 1979. As a result of the Second World War, the steamship was also stranded in Austria for two years from 1944, before being returned to Hungary at the end of the war. It was then owned by the Hungarian-Soviet joint-stock shipping company until 1955 when the Hungarian state-owned passenger shipping company MAHART was established. Since 1984 it has been part of the collection of the Hungarian Museum of Technology and Transport.

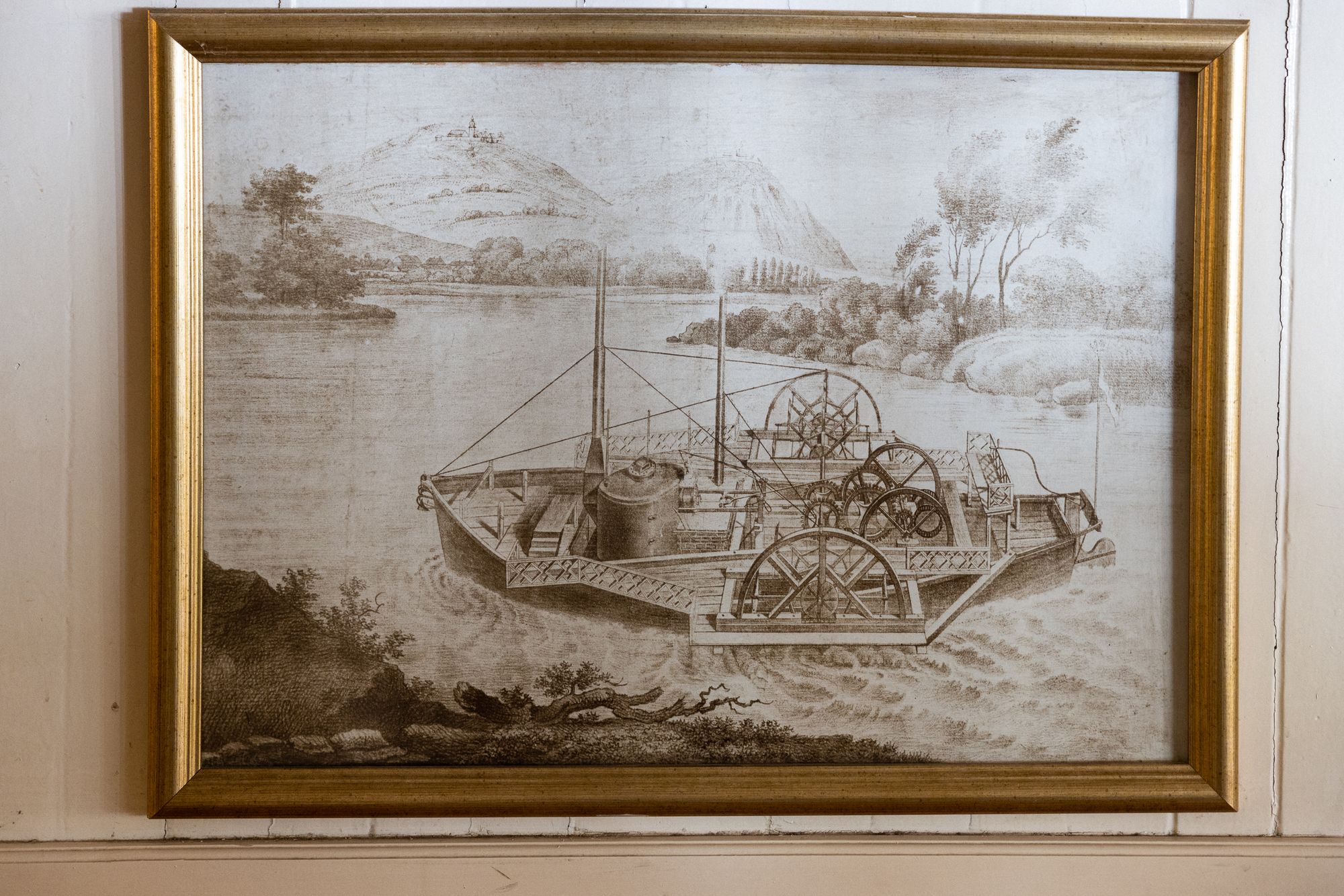

The Kossuth steamship is now mainly an artefact, with a restaurant on board. The Museum of Transport also hosts small temporary exhibitions on board: the current one is about the relationship between Budapest and the Danube. As Budapest’s public transport system began with boats two hundred years ago, the first public transport vehicle in Budapest can be seen on the wall of the Kossuth boat. The Carolina, built by Antal Bernhard, was the first steamboat on the Danube and the first public transport vehicle that was no longer horse-drawn or propelled by human power.

Of course, there are also permanent exhibits on board the museum ship: ship models, uniforms, decorative swords, and old nautical equipment, as well as the engine room and the paddlewheel system that set the steamer in motion. But, as Gábor sums it up, perhaps the most exciting experience is to relax on board, sipping a lemonade and admiring the city panorama, or rather, what this city is capable of.

Photos: Balázs Mohai

Kossuth Museum Ship | Web

Hungarian Museum of Science, Technology and Transport | Web | Facebook | Instagram

From old to something very new | Plato City Gallery of Contemporary Art, Ostrava

Discover the very best murals in Warsaw