What are the trends in ceramic design today? What should we look out for when buying a bowl, plate, or another ceramic object from a designer brand? How much can we believe the fancy pictures we see on Instagram? We asked Piroska Novák, design and art theoretician, curator at the Museum of Applied Arts, about the renaissance of retro objects, the emergence of hobby ceramicists, the market opportunities for professionals, and much more.

Let’s get started! Piroska, could you help us find out what the trends in ceramics are today, in 2021?

The field of ceramics and ceramic art has always been extremely colorful, diverse, and wide-ranging. The diverse usability of ceramic materials shows that diversity is still valid today. It is, however, much more difficult to survey this vast field and to identify the dominant trends. It is therefore fortunate that after so many years, this year the prestigious National Ceramic Art Biennale was held again in Pécs, giving a fresh insight into the situation in Hungary.[1] The overwhelming majority of the submitted works were autonomous, fine art-inspired works and the winners were exclusive of this genre. Of course, there were also a few objects with a practical and utilitarian function that could be classified under the umbrella of design, although the number was much smaller. Unfortunately, the percentage of artworks in the newly launched student category was also low. It was surprising that, despite the open call for entries, the growing number of self-taught ceramicists did not take part in the professional competition.

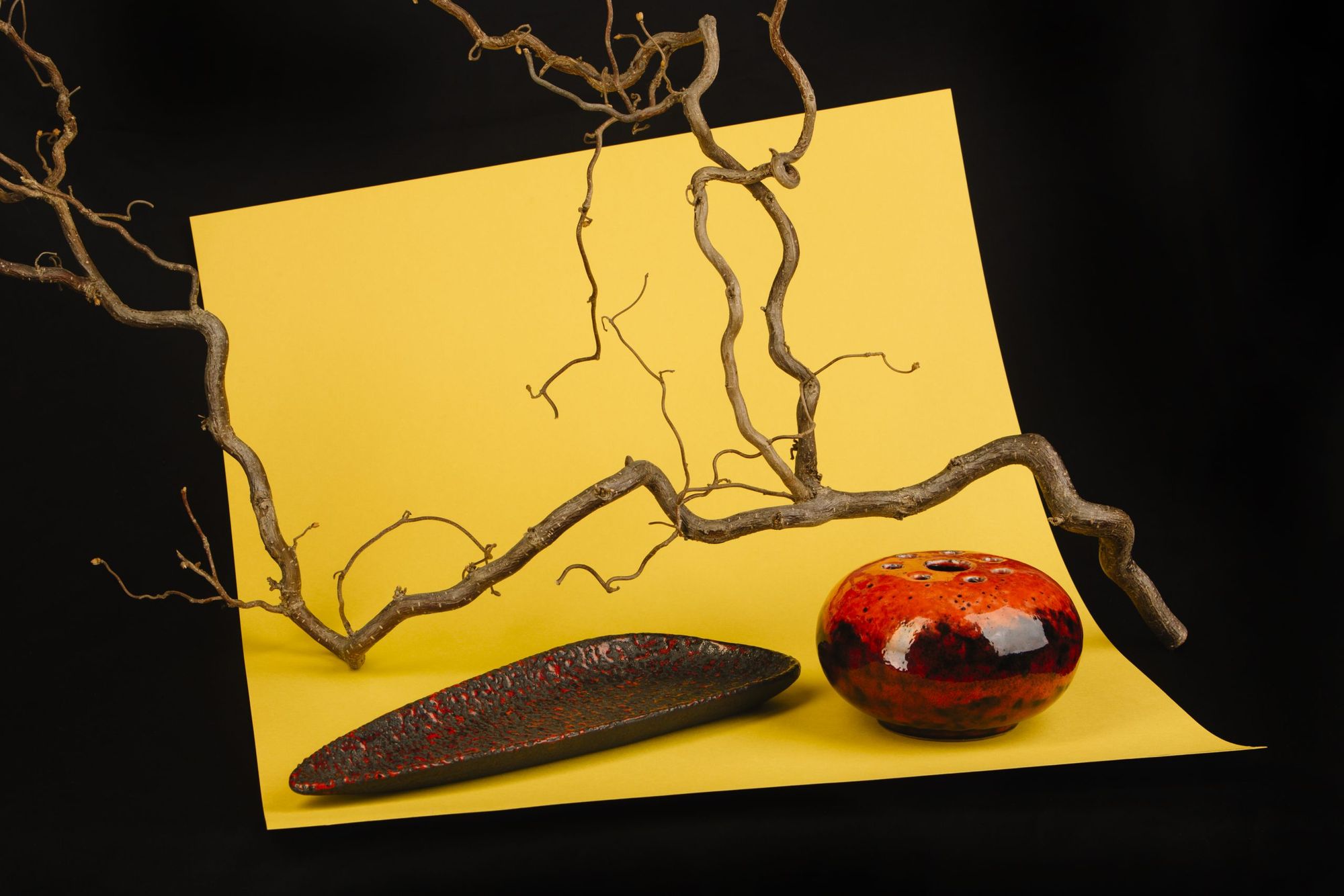

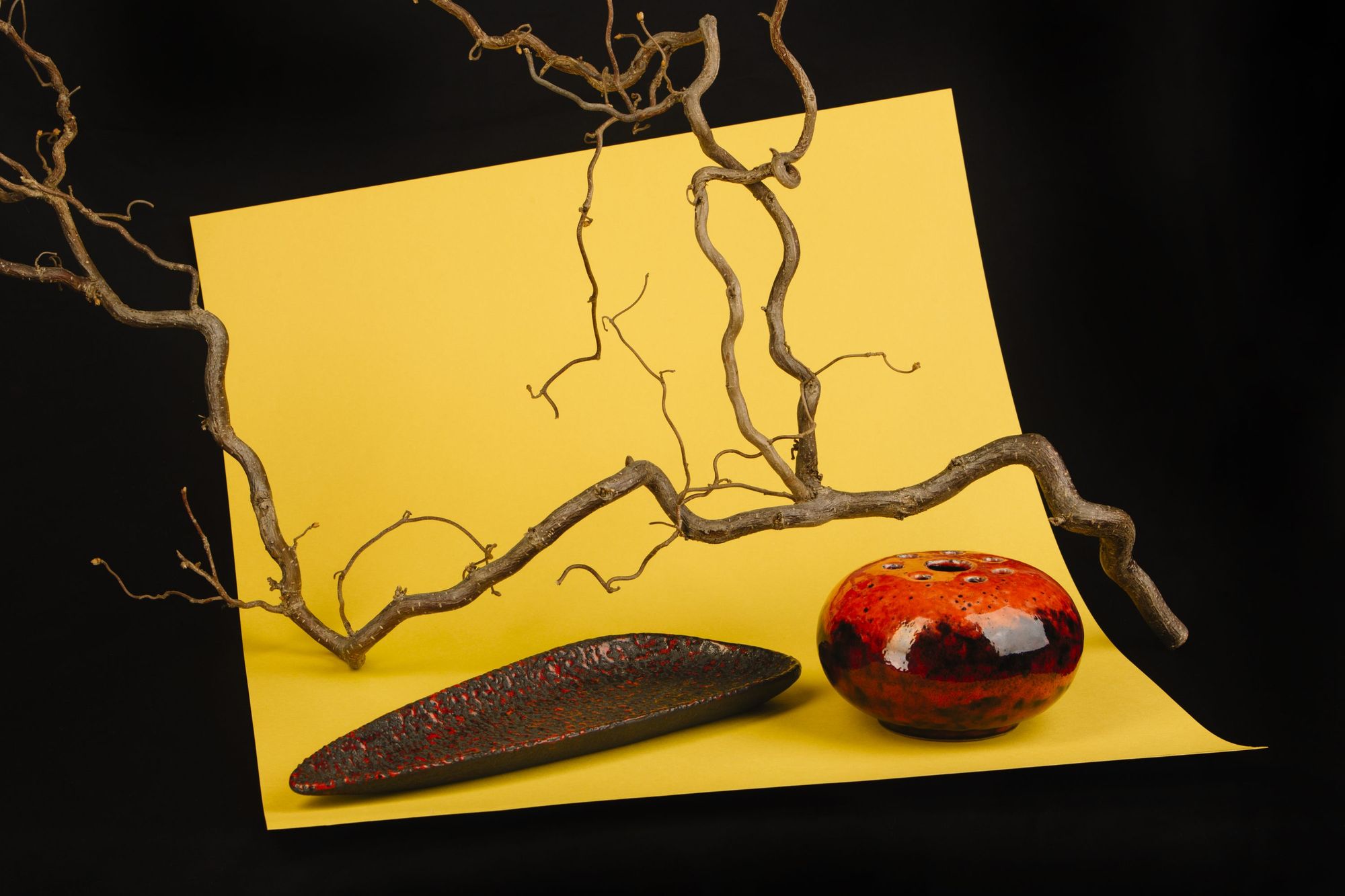

Many of the award-winning artists use traditional high-temperature wood firing technique, which has been gaining popularity for many years. The aesthetic acceptance of wood-fired ceramics – which can range in appearance from airy celadon glazes to rustic, natural ash glazes, depending on the intention of the ceramist and the fire—is also growing. This trend is often labeled as a Japonising style, even though most artists using this technique try to give their objects their own character, keeping in mind that Euro-Atlantic culture can only have a superficial knowledge of East Asian aesthetics, even if we learn the meaning of wabi-sabi, kintsugi or chado. The technique of wood firing requires the highest degree of professional knowledge and experience.

The exact opposite of this is the group of self-taught artists, who work with low fire clays, using ready-made glazes ordered from catalogs instead of their own glazes, and who mainly create decorative objects for interior decoration. Their work is often asymmetrical and clumsy, with a pronounced irregularity of hand-shaping that conceals or counterpoints their lack of skills of the Potter’s wheel or that of professional knowledge with a mask of uniqueness. This direction can be called, for want of a better word, autodidactic or naïve ceramics. The technical quality of the work of naïve ceramists is inferior to that of their skilled counterparts, but they are more successful in branding, communication, and self-management.

In addition to the two big trends, there is also a narrower path, that of design-led ceramics, where the creator is both designer and ceramicist (designer-maker). Their products are produced in larger series, they are a mix of utility and decorative objects, jewelry, furnishings: either on commission or through careful observation and analysis for a well-chosen niche market.

There is, however, a great lack of objects that renew the traditions of Hungarian ceramic culture in a meaningful way, that process tradition, even with the tool of humor (see the case of a quality souvenir object such as a permanent veterinary horse), as well as of socially sensitive ceramic objects and projects that promote sustainability.

The gastronomic revolution has been booming for a few years now, and this lucky turn of events has in many cases opened the eyes of restaurant owners to the idea of having a local designer design the kit for their bistro, fine dining restaurant, or even tea room. How much more can such a kit offer, and what kind of local designers can we identify in this segment?

Indeed, it is in line with the principles of gourmet and high-end gastronomy for a restaurant not to choose from the catering sets available on the market, but to design a unique range of tableware for the place, with distinctive objects that add to the complex taste and aesthetic experience of eating an exclusive seasonal menu. One of the first such collaborations between a restaurant and a ceramicist in our country was the collaboration between Olimpia and Júlia Néma between 2010 and 2012. Júlia used wood-firing techniques; her vortexes are still going strong today, with not only restaurants but also tea rooms, cafés, confectioneries, and even individuals and families requesting wood-fired vessels made exclusively for them. The characteristics of the technique, the interplay of fire, heat, and ash, the controlled randomness, the fact that each object becomes unique and unrepeatable, are a particular favorite with chefs who have grown tired of the snow-white china plate that has long served as a blank canvas for their food creations. The benefits of industrial production—such as reproducibility, cost-effectiveness, durability, dishwasher compatibility, stackability – have been eclipsed in gourmet gastronomy. At the same time, there are rules that cannot be ignored: the use of solid-fired masses and food-safe glazes (spectacular glazes such as crystal glazes, lithium-containing glazes, or luster glazes are not suitable for food use).

Besides Júlia Néma, I would like to mention Tünde Ruzicska, Csaba Szabó Ádám, Enikő Kontor, Eszter Fehér, Balázs Botos or some members of the CriminalCraft group, who often collaborate with restaurants. More recently, naive ceramists have also ventured into this field. This is why the new regulation is so important: ceramic objects placed on the market must indicate whether they are suitable for eating purposes or will come into contact with food. To avoid a repeat of the infamous 1981 case in Veszprém, when two little girls were poisoned with lead from a teapot marketed by the Applied Arts Company.[2]

Lately, more and more people are “getting into ceramics”—I use this expression deliberately, as it is usually amateur or other artists who have decided to make ceramic objects. How good is this kind of democratization for the craft? What are the potential dangers behind the fancy Instagram image?

Democratization is an apt term since anyone can make ceramic objects for the pleasure of creating, for recreation, or even for therapeutic or skill-building purposes. More and more workshops are opening up specializing in this service, access to materials and equipment is becoming easier and more and more people are offering kiln hire. In terms of quality, however, there is no democratization, since pottery is a profession, a craft that is studied over several years, just like ceramic design at university. It’s good if a craft becomes popular, and if ceramics classes in schools, which were closed down a few years ago to cut costs, are restarted, and if more people apply for quality training places. However, it is damaging if, after a short course, people feel they have become a craftsman and start selling their objects, for example on social media. My advice to buyers is not to fall for the filtered images you see here or the number of followers and heart-shaped likes. Look at the object in person, touch it, pick it up, try it—that’s autopsy. And feel free to ask the ceramist: what material is the object made of; what temperature was it fired at; can it come into contact with acidic elements, tea bags; how heat-resistant; how flame-resistant; is the decoration dishwasher-safe? et cetera.

We must not overlook the fact that most of the former ceramic factories have disappeared, and only the biggest “big fish” of the traditional style, such as Herendi or Zsolnay, remain. So, the question might seem obvious: what is a ceramic designer to do on the market today?

Your question is complex because it takes you back to historical precedents. After the Second World War, most domestic ceramics and porcelain factories and manufactories were nationalized and then brought under central control. From 1963 this central body became the National Company of the Fine Ceramics Industry (FOV), from 1968 the Fine Ceramics Industry Works (FIM), which brought together eight factories of eleven plants. Centralized management covered everything, including the product range. The only exception to this was the Herend Porcelain Factory, which at the time was still exporting heavily abroad, and thus was able to maintain its artisanal traditions. As a counterpoint to the factory products, the Applied Arts Company and National Alliance of Cottage Industry Co-operatives offered an alternative in the form of unique, small-scale objects. The FIM ceased to exist in 1982 when it became clear that the centralized planned economy system had been unprofitable throughout and had kept alive factories that could not survive the regime change without the Trust. Only the biggest ones survived. The product range of Herendi, Zsolnay, and Hollóházi, which can be recognized anywhere, is a huge trap that hinders real innovation. It is difficult for a young, freshly qualified ceramic or porcelain designer to adapt to the constraints rooted in tradition. This is partly why this field is lacking today. So, what can a fresh ceramic graduate do with him- or herself and his or her skills? Gabriella Farkas, who will graduate in 2019 from MOME’s Master of Ceramic Design, explored this very question in her thesis. She was already part of a team of young ceramicists – now called CriminalCraft – who create together at one place, with common principles but slightly different goals and styles, and share the ever-increasing tasks that a designer or brand has to take on and carry today. This, for example, is a response to the question and the situation, although it should be remembered that there were also precedents for this in Hungarian ceramic culture, such as the Terra and DeForma groups, which took shape in the uncertain years following the regime change, the former representing the autonomous and the latter the applied field, with resounding successes that shook up the entire profession.

There are ceramicists—artists and designers alike—who have developed a special, unique technique that makes their work instantly recognizable. In the long term, this tactic is as dangerous as a factory. Continuous innovation can be facilitated by experimenting with masses, glazes, techniques or by alternating between autonomous and applied fields. It is also possible to catch the wave of the aforementioned gastronomic revolution if there is no pandemic. In addition to the traditional scholarship applications and annual events, the attention of collectors and gallerists is also turning to ceramics. For the time being, however, they are more focused on autonomous works.

Retro ceramics are back (or still) in fashion. Once thought of as ugly, unwanted objects, they are now enjoying a renaissance. What could be the reason?

I am often confused by the term “retro” because it is not typically defined any further, nor are terms such as “antique”, “vintage” and “turn of the century”. If by retro you mean ceramics from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, then they are indeed fashionable, partly because of the historical antecedents I mentioned, as most factories no longer exist, and therefore their objects are rarities. On the other hand, for the older generations, they represent nostalgia, that is, the embellished past in the present, and for the younger generations, these objects represent exoticism. It is important to note that, even if the ceramics of the period are indeed a little ‘ugly’, as you put it, most of them are of a much higher technical quality than the work of the naive ceramists of today.

It would be worthwhile to use this fashion wave to do meaningful research on the ceramic and object culture of the period, with a scientific, interdisciplinary, holistic approach. Because the social network sites and online marketplaces already mentioned often use the terms retro and antique with a confusing lack of precision: what is not retro here is antique, and vice versa. In addition, false or half-information is often given about the objects. Fortunately, there are some refreshing exceptions.

The photos accompanying the interview were taken by Lilla Liszkay. The objects in the photos are the property of the authors.

[1] For more, see: Piroska NOVÁK: Újraindított hagyomány (“A tradition rebooted”). National Ceramic Art Biennale 2021, Pécs. In Hungarian Applied Arts. 2021/5, 2-8.

[2] For more, see: Katalin BOSSÁNYI: Mérges-mázos (“Poisonous and angry”). Miért tiltották meg az Iparművészeti Vállalat egyes kerámia edényeinek árusítását? (“Why was the sale of certain ceramic vessels of the Applied Arts Company banned?”) In Népszabadság. Vol. 40 No. 11. (14 January 1982), 5. The case is also briefly summarised by József Vadas in the introduction to his study. In Nem mindennapi tárgyaink (“Our Not Everyday Objects.”), The Manufactory of Applied Arts, 1983. Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó, Budapest, 361-383.

Three-winged aircraft concept could revolutionize aviation

Pipe-like house reflects the surrounding landscape