How does a designer navigate among different fields? How do different cultures affect their work? What is an infinite source of inspiration in a multifaceted creative activity? Ákos Huber, currently living and working in Portland, is an architect by profession, but he is familiar with industrial design and drawing, as well. Interview.

You studied at the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, in the department of architecture. In the past years, you’ve worked in Berlin as part of the Erasmus program, spent a year in Munich and London before ending up in Portland. Could you tell us more about your journey and how it all affected your designer vision?

I spent 6 months in Augsburg and Berlin back at university; in the former, on a study scholarship and in the latter, as an intern, and I was impressed by the vibrant cultural life of the cities. I think this period was the beginning of my journeys later on. After graduation, I couldn’t find my place at home, I wanted to see new countries, new cultures. I feel that my curiosity hasn’t ceased since. In the first years, I and my wife followed each other to wherever one of us received a good opportunity. This is how we ended up in Munich, London and five years ago, the US.

I think I’ve changed a lot, and became more open due to my successes and failures, which escorted me every time I settled in a new place.

So far, Portland has worked out for me best. Oregon is an amazing state with rainforests, deserts and ocean beaches. The proximity of this latter is what I like the most: I visit it as often as I can. The horizon constantly changed by the misty air, the sandy beaches and the black rocks make the Oregon coast the most lyrical place I’ve ever been to.

Even though you’re an architect graduate, your activities are very diverse: expressing yourself in different ways with different tools is crucial for you. Take industrial design, for instance, where you experiment with different structures and combinations of materials in the form of furniture. What inspires you and what was the first piece of furniture you’ve ever made?

I’m currently an architect by profession. In contrast with the large-scale and complex vision that’s typical in my job, I think, what I like the most about designing objects is that I can have a much bigger impact on the result, besides, a quicker turnaround is also an attractive factor. And the touch of material is also indispensable for me.

The first piece of furniture I made was in my first year, under the supervision of Tamás Nagy. My task was to design furniture for the participants of the Last Supper. I presented a three-legged seating platform on display, in the spirit of symbolic trinity, strong structure and function. The object had to be built: it was then that my love of workshop work began. Looking back at the object, I can see a similarity with the Chair of the Moment: an interesting parallel that I have only just become aware of.

I think the further one finds inspiration from the object to be designed, the more exciting the final result will be. In the case of a piece of furniture, this can be music, a piece of literature, a natural shape, pretty much anything. For the design of the Wing Sofa, I drew inspiration from my experience with the statue of Nike of Samothrace in Paris.

Materials are crucial, as well, which is inspiring in itself. In my project called Fungi, I used bike tires and exploited the material’s values to create a flexible seating surface. The user is surprised to find it comfortable when leaning on a seemingly hard surface. The bench was on display and in use outside the Portland World Trade Center in the summer of 2018.

Besides experimenting with the material, your furniture is also special because they are very statuesque in form, too. How does the creative process take place for you?

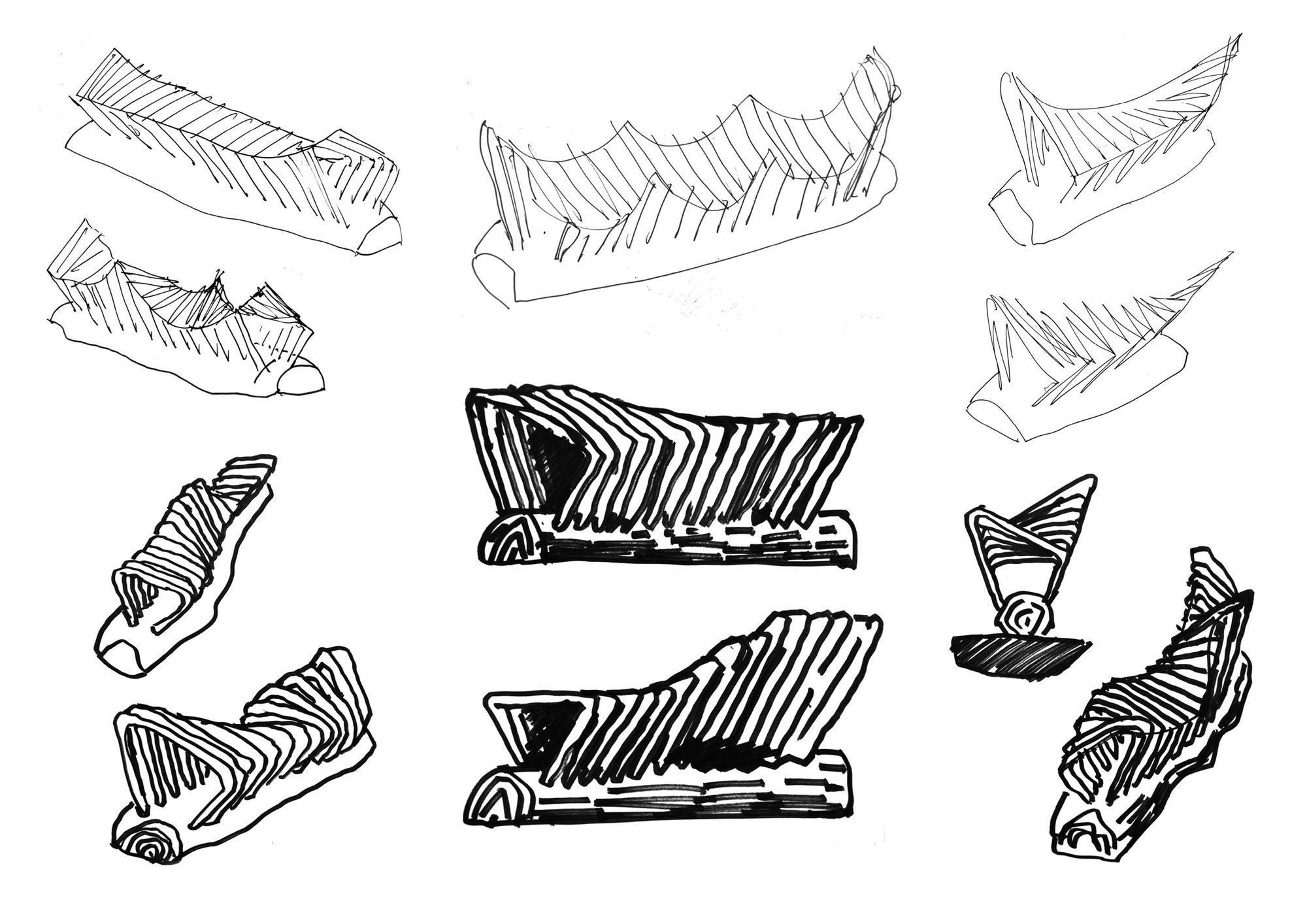

The designing process always starts out with modeling, sketching, aimed to constantly improve the structure, the function and the shape. I’m practically spotting for flaws that I either correct or use for my next model. This kind of imperfection, randomness, play that escort handcrafting are very important for me. At some point, I might use a computer to help the accurate execution. Besides, prototypes are made for the seating, which is the fine-tuning stage. The aim of the process is to get to the point where I don’t want to take anything away or add anything to the object. The final object is usually built by myself in a workshop in Portland: it can be seen as a kind of meditation.

I always try to find a challenge that takes me in new directions. For example, with the Chair of the Moment, I was very preoccupied with the idea of an asymmetrical chair, which led me to a seemingly random but very consistent construction principle.

I like an object or building to have a strong character that comes not from trends, but from structure, context, a strong sense of community and a sincere use of material or an instinctive vision of the creator.

Your latest chair was designed for the new exhibit of Art as chairs. What’s there to know about this platform and the concept of your new piece?

Art as Chairs is a really exciting Instagram page, which is different from other pages in the way that it shares lesser-known pieces instead of the boringly repeated classics. The creator of the platform is visual artist Joe Horner, who also lives and works in Portland, and also had works at the exhibit. As suggested by its name, Art as Chairs treats the borders of design and visual arts flexibly, often to the point of treating them as one.

My latest chair was named The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, which I created using various accumulated cardboard boxes. This is practically a collection consisting of three cubes. Each cube has a different texture: the first has the beauty of a honeycomb structure, the second a random layering of different types of material, and the third a rubber glaze for a particular visual effect. I think these works can be called sculpture rather than furniture.

In the designing phase, I often thought of sculptor Noah Purifoy’s outdoor museum in the Joshua Tree National Park: the scattered large statues consisting of different kinds of waste and the surreal structures have an unbelievably dramatic effect in the Mojave Desert in California. These creations are made of objects that everyone has already thrown away, and yet they stubbornly resist the often harsh weather conditions.

In your spare time, you do not only design furniture, but drawing also plays an important role in your creative work.

I’ve used drawing to communicate since I was a child; it’s a very personal genre for me.

The drawings I make during my journeys help me get to know a certain place, discover the ratio systems and provide opportunity to fill the view with my own thoughts and emotions.

Flipping through my book of sketches, it’s interesting to see how I can associate memories with almost every single one of my journey drawings: the trace of raindrops on the paper in the Berlin flea market, the sudden anger I felt when my marker was running out of ink in front of Hayward Gallery in London, or how old folks were playing dominoes in Bambi Café in Budapest.

Let’s get back to your architecture for a moment. In Portland, what projects did you participate in and what were the main differences compared to your projects in Berlin or England?

There are numerous differences between European and American architecture: measuring units, structure and building techniques or the use of space, to name a few. Oregon belongs to the Pacific Northwest region of the US, and mostly uses wood as a building material, more precisely pine and cedar. This contrasts with the use of concrete and brick, which is typical for Hungarian or German architecture studios. In general, the living space per person is larger here than in Europe. Due to its history, the country’s built heritage is not as rich and varied as on the old continent, but the range of natural assets is incredibly rich.

I started working in Portland for the Allied Works Architecture. I worked on the extension of a family house, a café, the building of Nike campus and several applications. From this latter, maybe the buildings of Palmer Museum of Art and Sundance Film Festival were the most exciting. I learned a lot regarding design methodology: there were a lot of high-quality concept models, diagrams, graphics, publications for the plans. It was good to see up close how much emphasis is put on these things. This way of working reminded me a bit of my university years.

Now, I work at Daniel Toole Architecture. They’re a young architecture studio with a team of three of us. We share a similar set of values and have some very promising projects that are about to enter the construction phase. Current projects include a weekend home on an island in Puget Sound, a family house built around a basalt cliff and a brick apartment house. The structure of materials, mass shaping and experimenting play a crucial role in these projects, as well.

With so many activities and interests, where do you see yourself in the near future?

I’d like to continue what I’ve been doing and also work on my own projects as much as possible. I’m interested in crossing scales and media. The artists I look up to the most are also artists who have worked in several genres. I’m curious to see where this path leads!

The Ukrainians may have a chance to win | Exclusive interview with Jan Malicki – Part II.

Revolutionary smart device for the blind and visually impaired from Envision