At the next stage in the evolution of user-centered design, our wider environment becomes the primary user. Here is part 5 of our design thinking series, written by a Frontira expert.

Espresso: the most honest form of coffee. Aromatic roasted coffee beans are finely ground, compressed, and brewed under high pressure with near-boiling water. A ritual crowning of a slow lunch, a key to our survival on long Thursday afternoons. Sitting on the terraces of cobbled Italian streets, it is the lubricant of entire communities. Every cup of espresso is an experience.

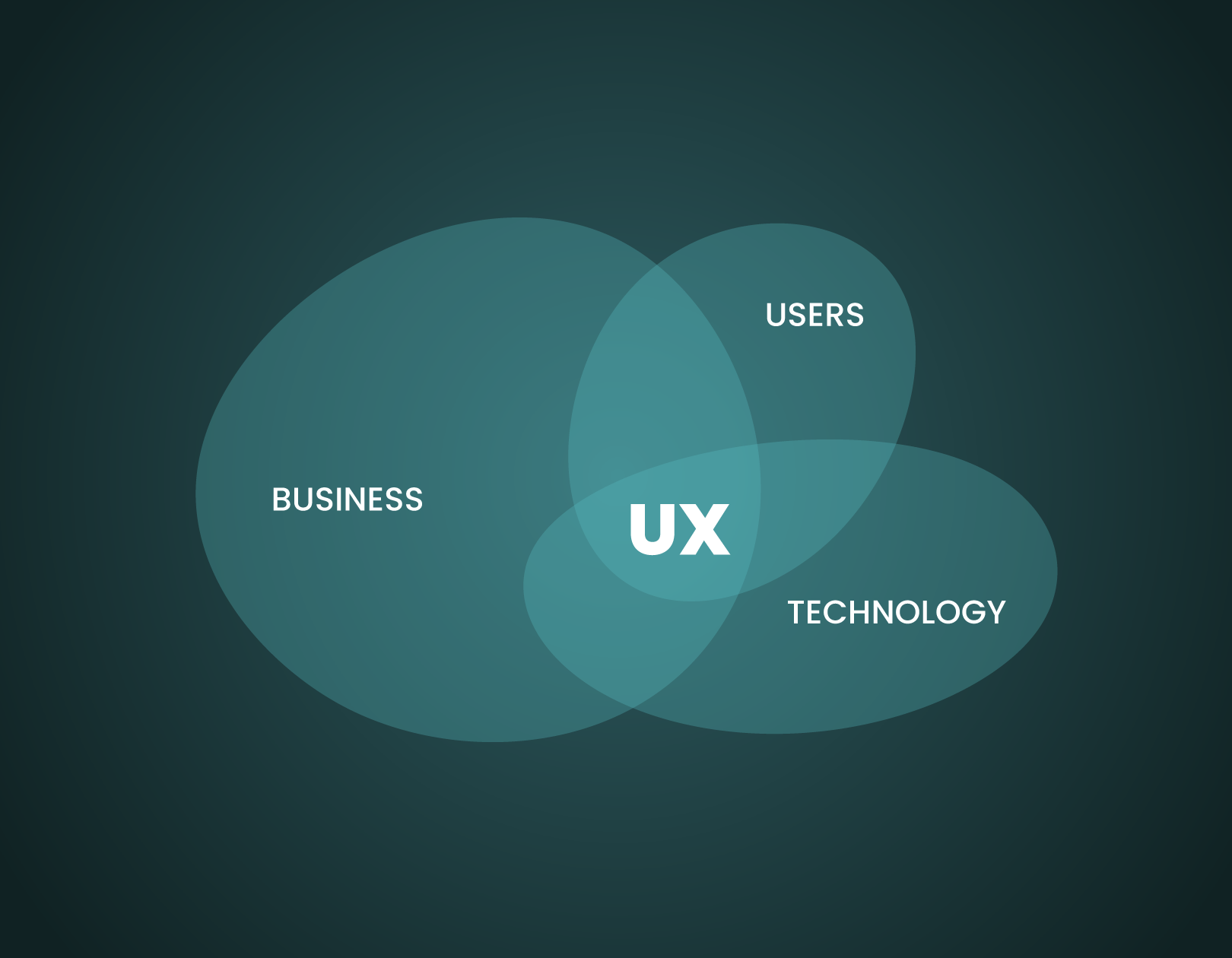

These experiences were taken to new heights with the advent of capsule coffee. This innovation is a striking example of the gold ratio of user-centered design.

It is appealing to people, that is, consumers, because it is delicious and extremely easy to prepare. More convenient than any other coffee brewing method, and the result is always consistent. You just can’t mess it up.

Both the manufacturer and the shareholders have found their reckoning: the big business lies not in the coffee machines but in customer loyalty that lasts for years and decades. After all, anyone who buys a coffee machine will continue to buy capsules.

It is based on easily upgradable technological innovations that make the real coffee experience available in the comfort of your home: the ground coffee stays fresh for months in the special aluminum capsules.

Nespresso, the world’s leading producer of capsule coffees, has for many years embedded a sense of belonging to a global coffee elite in consumers through a carefully constructed brand image, look & feel and an otherwise well-designed user experience (for example, community building, exclusive atmosphere in brick & mortar stores, unique promotional offers). But in recent years, hairline cracks have appeared in the form of new-wave cafés, urban youth thirsting for better, more specialty coffee, and increasingly daunting and tangible sustainability concerns.

Decreasing caffeine buzz.

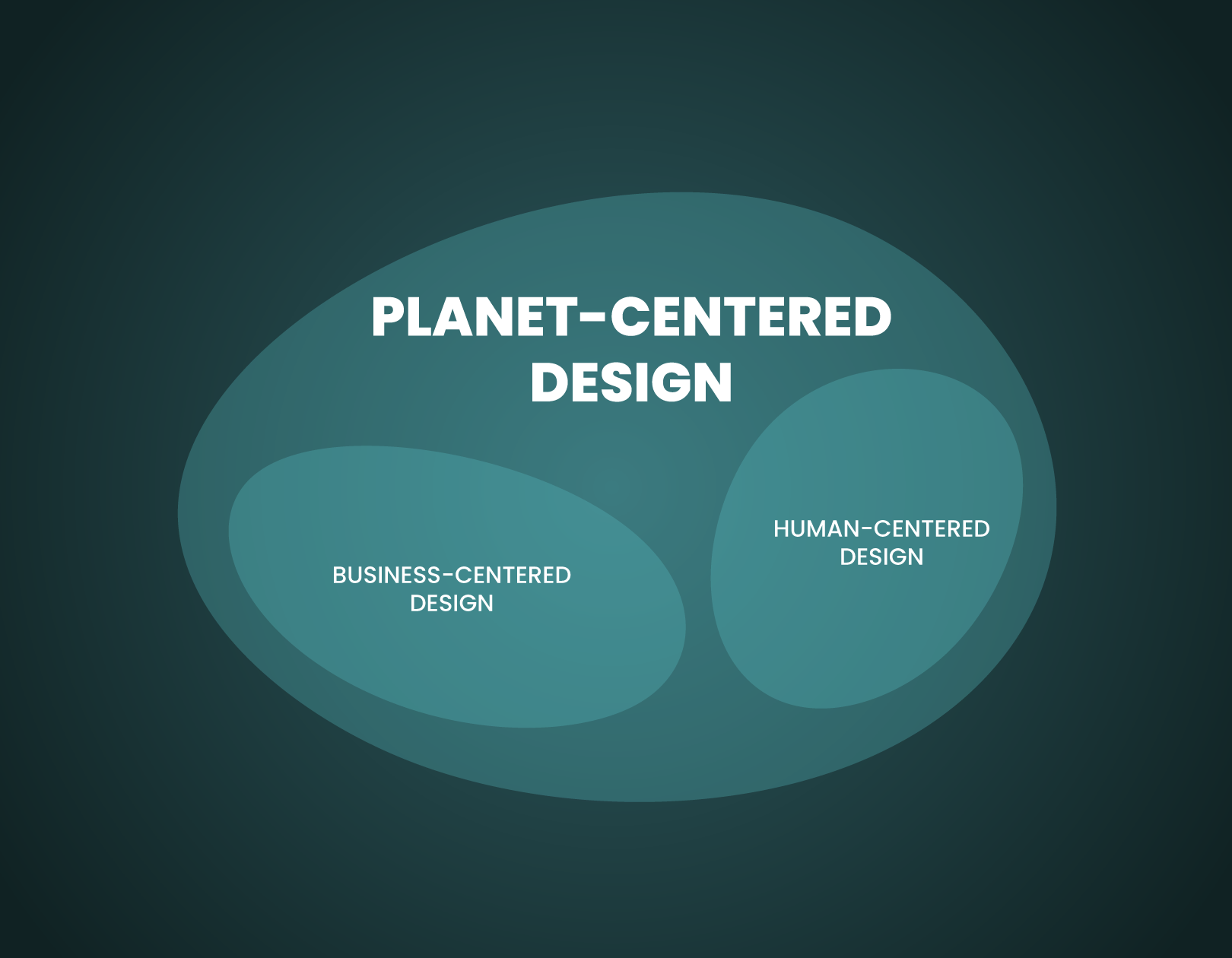

And that’s where the shades of the evolution of user-centered design that are gaining ground every day come into play: planet-centered design, social design, and community-centered design.

These frameworks focus on the broader context rather than the individual, subordinating the needs of the individual to environmental, social, or even community expectations.

So, when designing services or products, it is a priority to make a social group, a community, or the planet itself a key stakeholder. Obviously, this is a crazy difficult challenge, as it involves navigating a sea of interdependent needs, interests, conditions, values, assets, and opportunities that merge in countless layers. However, this is why it is crucial to consciously deploy processes and tools that help designers to navigate this rugged terrain. It is our task to understand these connections and how they relate to each other: only then can we create environmental, social, and technological interactions that are beneficial and sustainable for all in the long term.

Of course, to put this design theory into practice, we also need to be aware of the basics of user-centered design: the importance of empathy, journey mapping, prototyping, and so on (a recommended article on the topic tells the story of an ice-cream scoop and the human-centered design).

By adopting this more holistic, planet-centered approach in solving problems, we can avoid the situation in which Nespresso has found itself. Although the capsule is made of fully recyclable aluminum, there is a big gap between having the option to recycle and customers actually taking this opportunity to recycle.

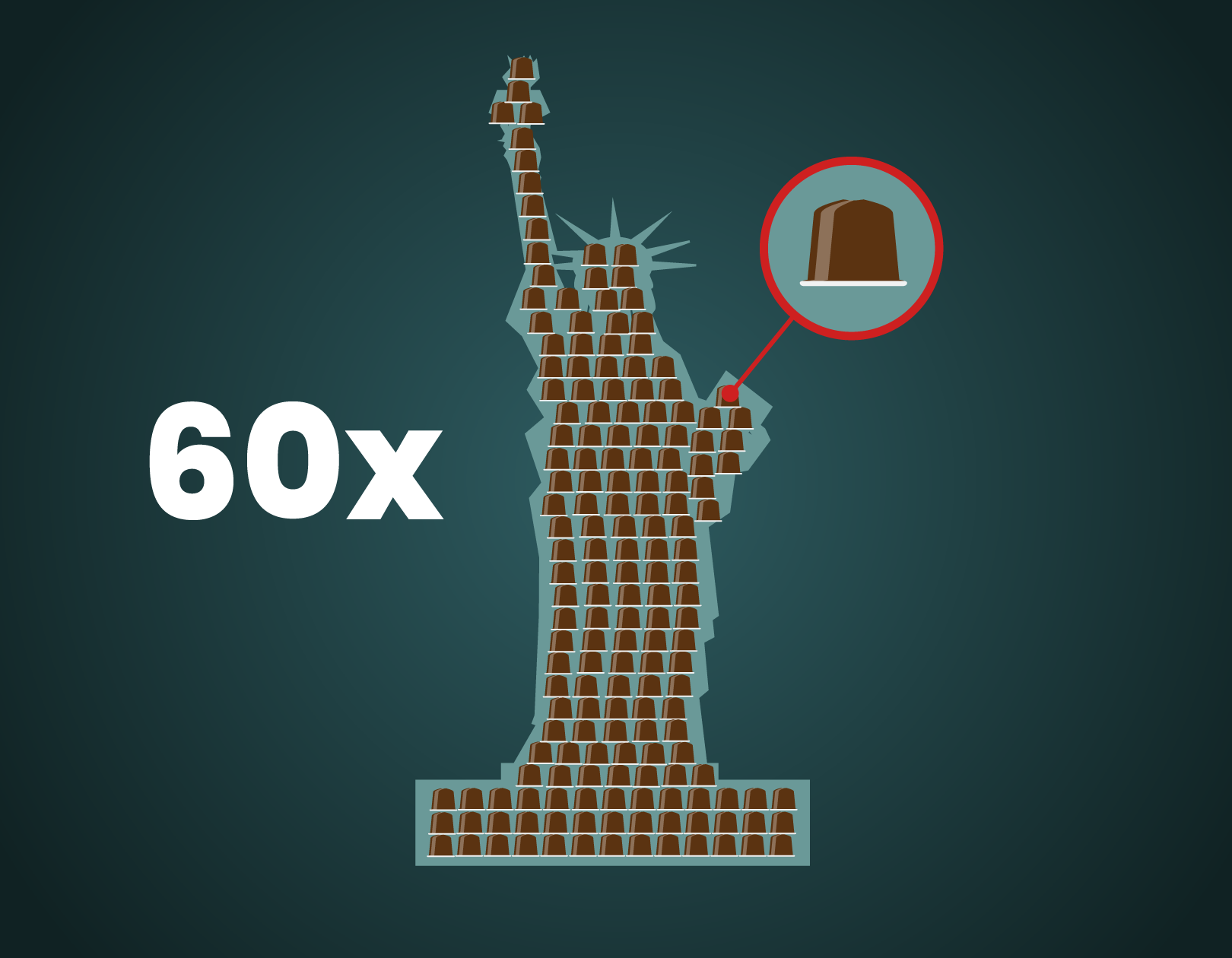

According to official figures, only 30% of the fourteen billion capsules sold each year are recycled. At 0.9 grams per capsule, this is the equivalent of 12 600 tonnes of aluminum going into the communal waste each year: sixty times the weight of the Statue of Liberty in New York.

We could talk about significantly lower figures if the environmental impact had been at least as or more prominent in the design process of the capsule concept as the consumer demand or the lighting technology of the capsule boutique.

Today, there are around 400 companies producing coffee capsules globally, and fortunately, most of them have recognized this challenge. Many sustainability-driven developments are now supporting the goal of reducing the environmental impact and returning as many used capsules as possible to the recycling channels. The directions are:

experimenting with more eco-friendly capsule materials,

introducing refillable metal capsules,

integrating take-back points into the shops,

sending free of charge, sealable bags with orders, in which used capsules can be collected and returned by courier for the next order,

in cooperation with local communities and municipalities, public collection points are being set up,

using communication campaigns to educate and raise consumer awareness,

and in Switzerland, used capsules can now be given even to the postman.

It is clear that there are multiple ways of approaching and tackling the same problem, be it technology, manufacturing, service design, or communications, and all these tools are in the toolbox of a conscientious designer.

The lesson to be learned from this is: whatever area you are creating new products and services in, consider the broader world alongside the individual. Let’s involve it in our thinking; let’s open the scissors wider, even if only on a micro-level, in small steps. This is not a sudden paradigm shift but a complex issue that affects everyone and in which we, as designers, have a special responsibility. If this may seem idealistic today, it is increasingly difficult to ignore in the future.

See the forest for the trees. While there is still a forest.

The author of the article is Csaba Kusztor | Consultant | Frontira

Frontira | Web | Facebook | Instagram

In our monthly series, we explore the various fields of design with the help of Frontira to understand the role of design beyond industrial design. What role does design play in building up human behavioral patterns? How can a service be a good experience and what digital product design toolset do we need for it? Calling itself the “company of strange problems,” Frontira answers questions like this, in an exciting manner and comprehensible form.

The doors of the nearly 100-year-old houses of Budapest will open again next weekend | Budapest100

The monumental halls of a monastery are brought back to life as a hotel