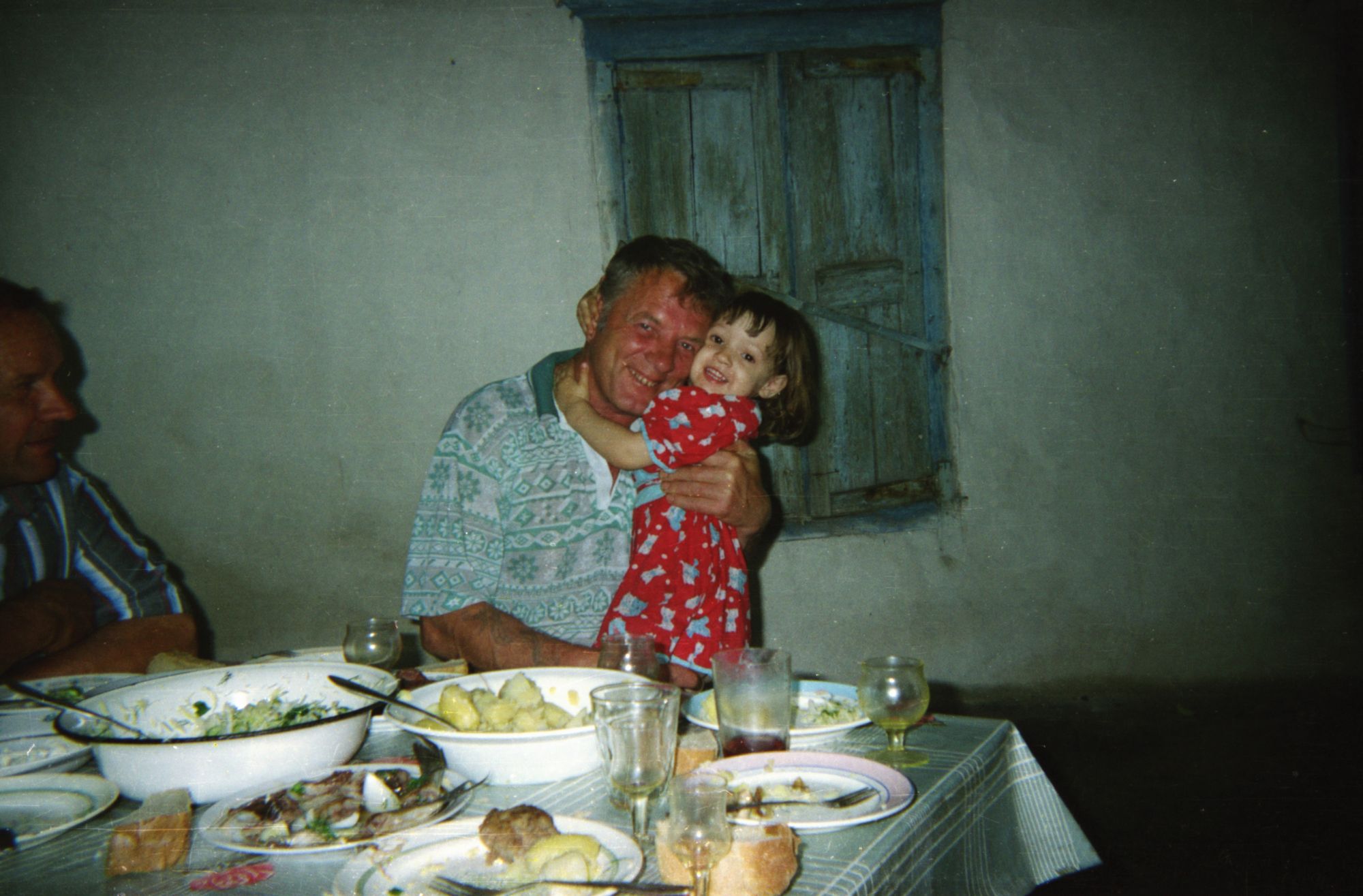

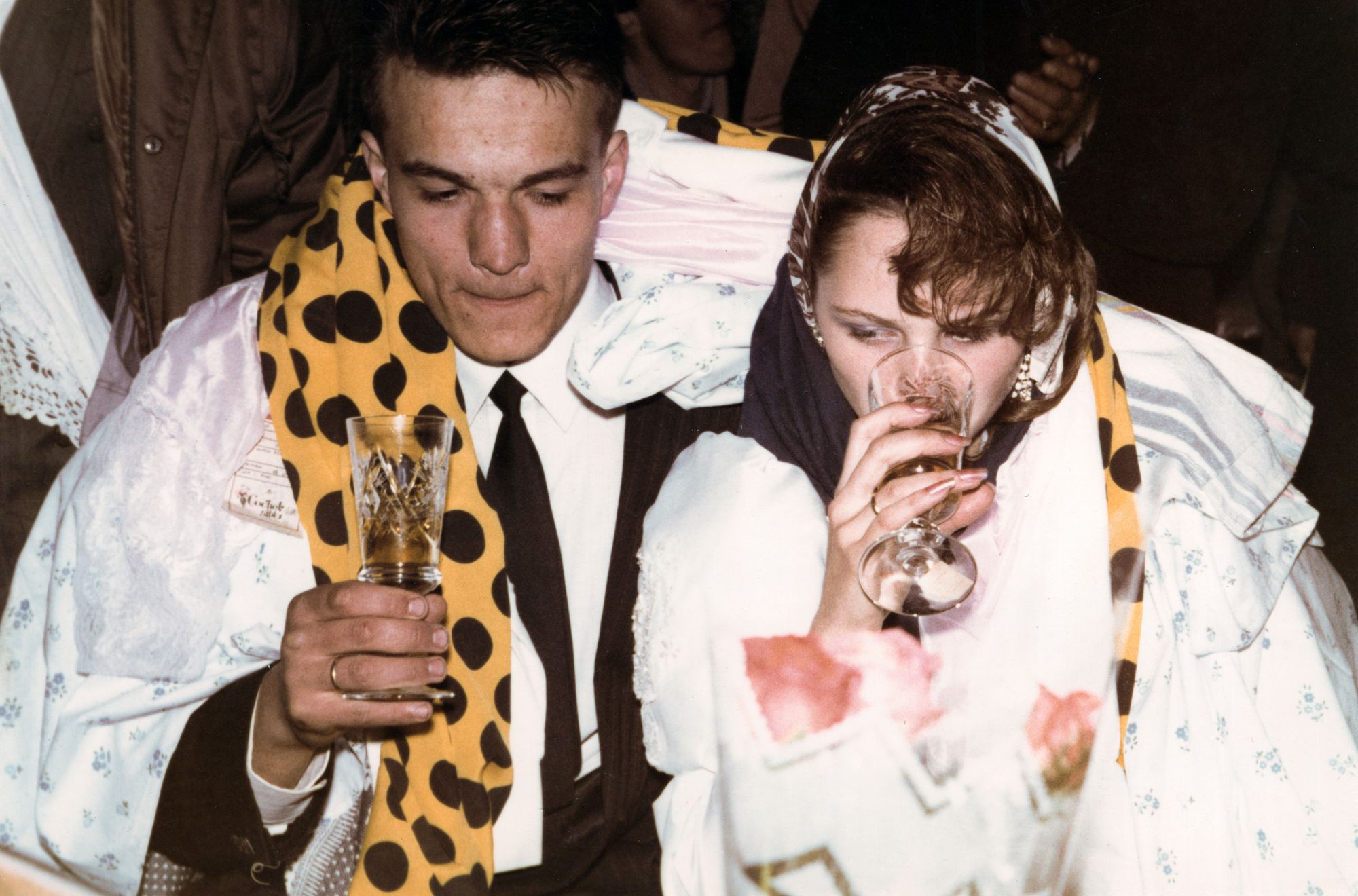

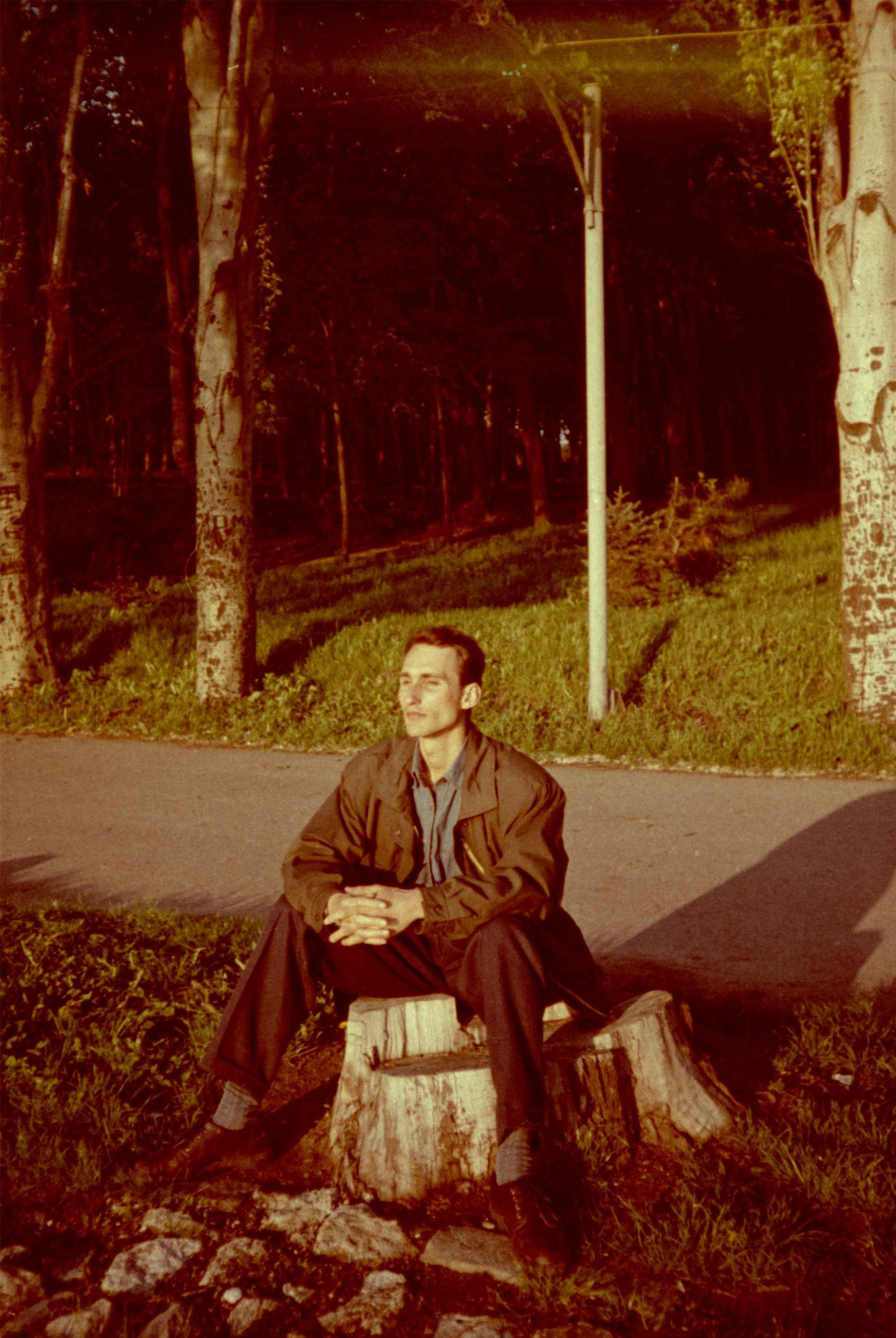

Adidas tracksuits, Coca-Cola, skirts with beach patterns, and parties. Despite the difficulties that followed the regime change, the vibes of the 90s were just as present in Moldova as anywhere. We can see all this and much more from the past of the country thanks to the Rama Albastră project, which rescues priceless Moldovan photographic documents. We spoke with Victor Organ about the beginnings, the value of photographs, the situation in Moldova, and the meaning of the project’s name.

How and why did you start the Rama Albastră project?

I have always had a deep fascination with the history and origins of objects. Understanding the genesis of events and their outcomes has always captivated me, particularly the process of cultural, musical, or architectural change and its impact on society.

When the Covid pandemic cost me my job, I had hoped to find stable employment with benefits. That’s how I found myself working as the lead specialist in photographic document valorization at the National Archives. However, the archive lacked photographs dating back to the Second World War, or earlier, as the Soviet Union had not prioritized the preservation of documents from that period. Consequently, we launched a project to collect photographs from the interwar period, though most of the photos in the archive had a propaganda slant that presented communism in a positive light.

Unfortunately, for various reasons, the collection project was eventually terminated, and I resigned soon after. It was then that I conceived the idea of creating an archive of photographs sourced from old family albums, with a much more authentic and documentary nature, and without propaganda, even if they were from the Soviet era.

Do you collect family photo albums directly from people, or do people come to you to have them scanned? Do you also collect stories, such as audio recordings?

It’s both. Some people know about our project and call us to them, and we often make appeals to the people. The Rama Albastră project travels through villages and towns to collect old photos from family albums. Mostly, several families gather at the library, town hall, school, or museum and we start scanning photos and gathering information about them. Stories and audio materials we will start to collect at the beginning of May.

Many sites collect old photos, and your project does too. But you also collect photos from the recent past, from the 90s and 2000s. I think these photos are in the worst position: they are old enough to be analog, but not old enough to be considered valuable. What is your experience of how people treat their photos from these decades?

Young people who were born in the 90s and 2000s have shown a growing interest in photographs from that era. They desire to gain insight into their parents’ lifestyles, fashion sense, and leisure activities. The freedom with which individuals posed for photographs during that period and the vibrant colors that were captured by the photographic film have captivated the interest of the younger generation. The essence lies not in the value or period but in the emotions that the photographs evoke. The closer the era is to one’s personal experience, the more profound the journey into the past becomes. This fascination with photographs from the past is driven by nostalgia for a time that one did not personally experience.

The 90s was a decade of turmoil because of the political change in the Republic of Moldova. How is this reflected in the private photos?

The photographs taken during the 1990s primarily depict the ambiance of that time, familial connections, impoverished living conditions, the everyday life of individuals, and lastly, the fact that everyone was present at home and not traveling abroad. In the private photos from that period, we can see many socio-economic, cultural, and political problems that have worsened over time. Politicians’ decisions directly affected family relationships, the workplace, rather the lack of it, and most of all, in my opinion, the cultural patrimony of our country.

What is the attitude toward preserving objects and traces of the past in the country?

The Republic of Moldova is currently experiencing a state of crisis that is ongoing, and the livelihoods of its inhabitants are heavily reliant on the financial assistance provided by the European Union. Due to these ongoing crises, culture and heritage are not a top priority for politicians and ordinary citizens who are dealing with numerous problems. In my opinion, the responsibility for preserving cultural heritage should fall on the state, but it is unlikely that the government has the financial resources to do so. Our project aims to rescue a portion of the photographic heritage by utilizing our resources and donations to travel through villages and promote the importance of digitizing, preserving, and promoting photographs. We often come across photographs in poor condition—moldy, torn, stained, and sometimes left behind in abandoned houses. Even photographs taken as recently as the 1990s and 2000s show significant signs of wear and tear, requiring restoration through Photoshop—a task that I never anticipated.

Why did you choose the name Rama Albastră, which means Blue Frame?

I chose the name of the project Rama Albastră (Blue Frame) after a friend brought me a photo in a blue frame from an abandoned house. And I remembered that I have seen such kinds of blue frames in different regions of the country. I found that many old photos were kept in white, green, and black frames but most of them had a blue color. Now I’m happy that I chose this name for such a project.

What are your plans for the future? Do you have a photo book, an exhibition or a website in the works?

In the future, we intend to arrange seven distinct exhibitions of photographs in seven Moldovan towns, which are positioned in the north, center, and south. We can combine them to form a tourist route. Concurrently, we plan to visit many localities to gather pictures, so that we can create a website where everyone can have free access to view them. We also aspire to create a photo book, but currently, we do not have enough images. We have nearly 6000 photos, but we desire to publish only the most unique and valuable ones that hold artistic, cultural, and historical significance in the album. Our main goal is to promote photography as an art form, a historical record, and a national legacy in the most varied ways that can be possible.

Contemporary and classical coexistence in an art lover’s home in Warsaw

Cheap Ukrainian grain destroys Central Europe