More and more foreign productions choose Hungary because of the creativity and high level of expertise of our professionals, as well as the favorable financial conditions. As a result of this growing interest, Budapest is well on the way to competing with London as a European center of film production. The recent visit of screenwriting legend Robert McKee to the Hungarian capital to hold his STORY Seminar for professionals and aspiring newcomers to the industry is a sign of this. We talked to the writer about the responsibility of writing, the slow decline of cinema, and the public’s attitude to criticism.

“I’m not here to teach you how to write a Hollywood movie.” An odd sentence coming from a world-famous American filmmaker whose mentees include 70 Oscar winners, 250 Emmy winners, 50 DGA, and 100 WGA winners. But it is no coincidence that this sentence was uttered in the very first 90 minutes of the seminar.

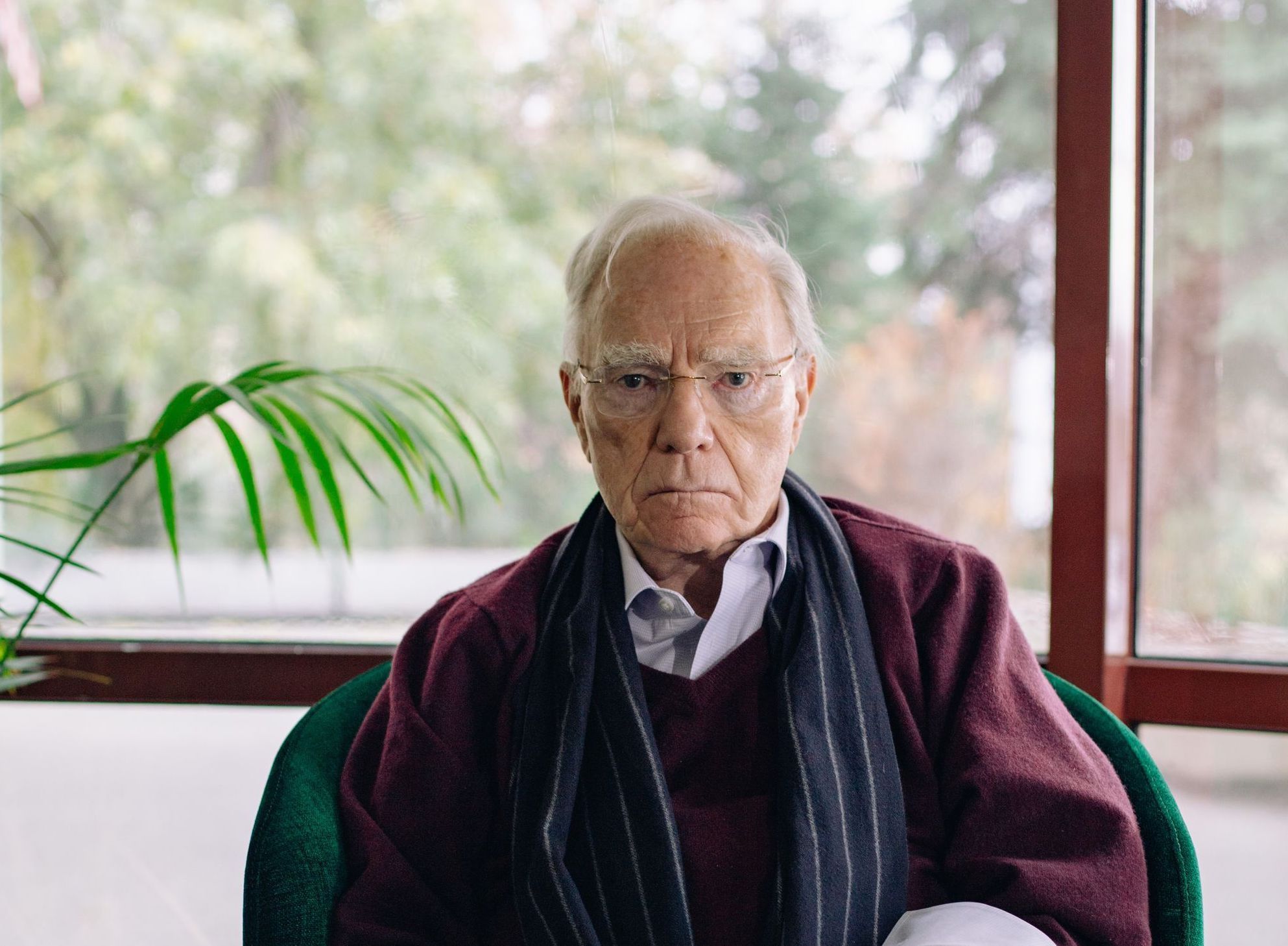

For anyone who has ever been involved in the film industry, Robert McKee’s name will ring a bell. His book Story is a must-read for screenwriters, directors, and producers at most film schools. The STORY Seminar, an intensive and exclusive three-day training course based on the book, is similarly popular. McKee, 81, rarely gives lectures, which is why it is a pleasure that he visited Budapest this autumn at the invitation of Norbert Köbli and the MCC Story Lab.

McKee’s ambition goes beyond fancy awards and blockbusters. The aim of the seminars is to take the lessons learned and create valuable works that not only contain culturally unique elements but also capture and convey to the audience the universal values of human existence. And although storytelling is as old as mankind, perfecting it is a highly challenging task.

During the three days, as one of the participants in the seminar, new doors were opened for me. The key lessons were not in the technicalities, but in understanding the passion and curiosity that characterizes most successful writers. The search for truth, the discovery of the motivation behind human nature and appearances through self-knowledge, is a never-ending process, and a never-ending urge to create.

This gave us the opportunity on the next day of the seminar to ask Robert McKee in private the questions whose answers must be heard over and over again.

What is the writer’s responsibility in the filmmaking process?

The writer’s responsibility is to express the truth: what is it like to be a human being in the circumstances that they create? To tell the story so powerfully and beautifully that we gain insight into the truth of how and why a human being does the things they do.

You mentioned in your seminar that the traditional cinema is slowly decaying. What could be the reason for this?

There are a lot of factors. One is, that the heart and soul of the film, though it has been denied for decades by directors, is the writing and not the directing. Without an excellent screenplay, the director can’t do anything of value. What has happened, is that the writers, at least in my country, are abandoning cinema and migrating to streaming television. So the best writing in America right now is in long-form television, but this is the tendency everywhere in the world. Writers are moving into streaming television, because they have more creativity and freedom, they can become the producers, and they have power. They also can become directors if they want to, and they can make more money. As a result, the cinema is slowly dissipating, and the truth has been finally expressed: what ultimately mattered at the cinema was not the director alone, but it was a collaborative art between the writer and the director. Long-form television is offering audiences more complexities of character, and deeper experiences over longer periods of time than the cinema ever could. In the 21st century, the long form will be one of the dominant art forms.

Another reason is that since the pandemic, people now want their services where they want them when they want them. And if they don’t have it with them in a particular place and time, and they are paying for it, it’s not convenient. The size of the screen versus the inconvenience, they will choose the smaller screen.

We live in a world of chaos and uncertainty. There are also many topics in modern culture that people get easily offended by. How should writers approach these topics?

Easily offended people are just another form of censorship. They are putting pressure on writers. This is not new and when I was a kid, the greatest censor was the catholic church. They had a list of films that you must not see. Writers have found genius ways to get around them, so I don’t worry about it. Writers are rebels, they will figure it out. What will happen is that these people will be embarrassed because they are so close-minded. It’s childish to be so sensitive to criticism. The kind of people we are talking about cannot face criticism. The harshest criticism you have in life is the one towards yourself. And these people cannot deal with somebody criticizing their behavior in some fashion, because they can’t criticize themselves. And if they can’t do that, how can they mature and grow as a human being?

Besides, the long-form television we are talking about—Better Call Saul, Ozark, Leftovers, Peaky Blinders—are stories about dangerous stuff. Criminality, sexuality, and political hypocrisy; they still have huge audiences. So if the easily embarrassed had any power, nobody would watch Better Call Saul. When you create something that is really superior, people will flock to it.

What is your opinion of Hungarian films? What do you think is unique in how filmmakers see this part of the world?

Lately, I have been paying attention to Hungarian films. With one or two exceptions, the films that I saw during the last 10 years at the most tend to be love stories in very painful situations. A love story in a labor camp, like Eternal Winter, or a love story in a meat processing factory, like On Body and Soul. Son of Saul is not a love story, but often they are about a relationship in very difficult circumstances. I have a feeling that these are metaphors for Hungarian life. Most of them have a historical setting and they are expressing a lament, a grief about a lost empire.

My overall feeling is that they are really good films and I’m impressed by them. I just wish they were more international. Hungarian films almost never reach the art movie theaters of New York City, which is unfortunate but it’s the nature of the market.

If you can give just one piece of advice for those who have just started writing screenplays, what would it be?

If I was to give advice to young writers, that would be: Don’t quit! It’s a very difficult art form to master and it will take very likely 10 years to make yourself into a writer. You’ll be willing to sacrifice a lot to reach what you want, so don’t quit!

Photo: Dániel Gaál

A Hungarian girl in Sweden wants to reduce the ecological footprint of the internet

Ukraine has to be careful – interview with Olga Pindyuk