Anyone familiar with the world of gastronomy knows that the essence of any dish goes beyond its flavors. It is the combined work of several fields that can make a meal an enjoyable and nutritious experience, which is why we are no longer talking only about chefs or pastry chefs, but about teams. The World Chocolate Masters has become recognized as the Olympics of the confectionery world, and this year a Hungarian competitor, Attila Menyhárt was one of the finalists, along with other experts.

I have praised the ONYX Creative Community in many of my previous articles, this democratic, inclusive collaboration, and catering system which I believe could reform the whole of Hungarian gastronomy.

The World Chocolate Masters pioneered as a prestigious world competition, and the competition’s finals held at the end of October, demanded complex thinking and teamwork from the participants, even though they ultimately stepped on the stage alone. Attila Menyhárt (whom we wrote about here) found himself in this position in the spring when he became the first Hungarian to win the Central European final. After the celebrations, the chef, who runs Meinhart Patissier, had to face the big challenges of the autumn finals. As a start, he received an 85-page competition description, in which the organizers detailed all the events: tasks, constraints, allowed ingredients and tools, timing, and risk factors. The reason for this was that even though everything had to be done on the spot during the three-day finals, all of this required plenty of preparation. The ingredients, molds, and certain elements had to be prepared and delivered to Paris, and the recipes and related lists had to be handed in at the beginning of the fall.

He faced seven assignments in the finals: #SHARE (a 3D-printed chocolate gift to share), #WOW (a 2 m high and 1.5 m wide window display made of chocolate), #TASTE (a day-fresh patisserie), #BONBON (an innovative bonbon), #YOU (a one-minute power speech), #TRANSFORM (a dessert adapted to the tastes of three different target audiences), #DESIGN (an artistic chocolate sculpture). The main focus for each event had to be placed on the buzzword of the competition (#TMRW—i.e. tomorrow) and the theme of their choice (#locallove), but it was also important that chocolate would get the most attention. This was helped by the ingredient’s customizability, as the head sponsor, Cacao Barry allowed participants to design their own Or Noir chocolate (which in Attila’s case received the name ‘Epicure’) based on their personal taste profile.

So it is clear to see that art, science, and gastronomy have come together, not only to raise the stakes but also to bring a new color to the world of classic French pastry. Of course, this didn’t make the preparations any easier, and one of the obligatory elements, the 3D-printed chocolate mold made by Mona Lisa, for example, arrived with a considerable delay, and after this summer’s salmonella scandal, most chocolate factories were closed down for safety reasons, pushing back the delivery of other elements as well. That is why Attila focused on working with partners during the preparation process with whom he could focus on other aspects of the tasks, and who understood and embraced the world he imagined.

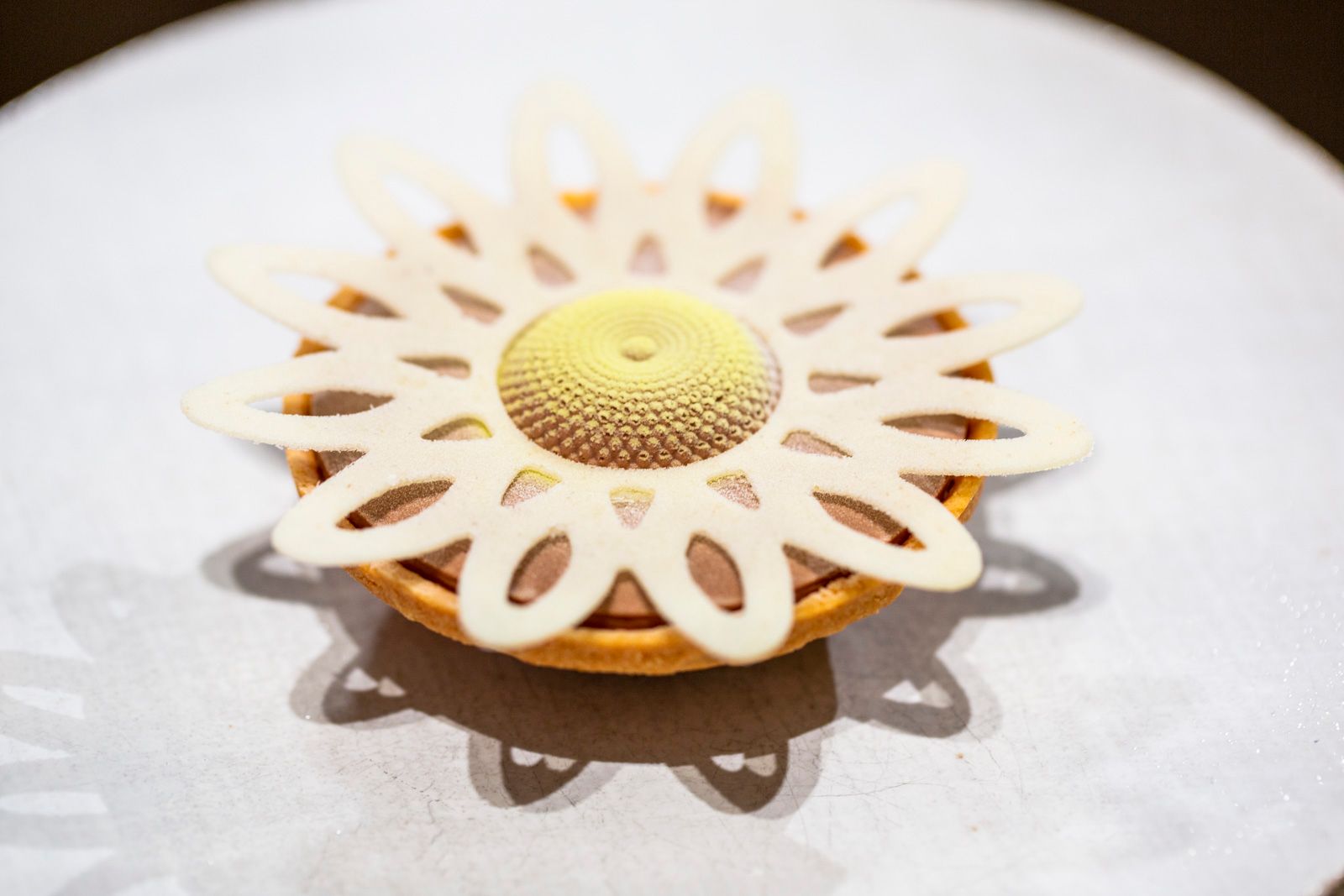

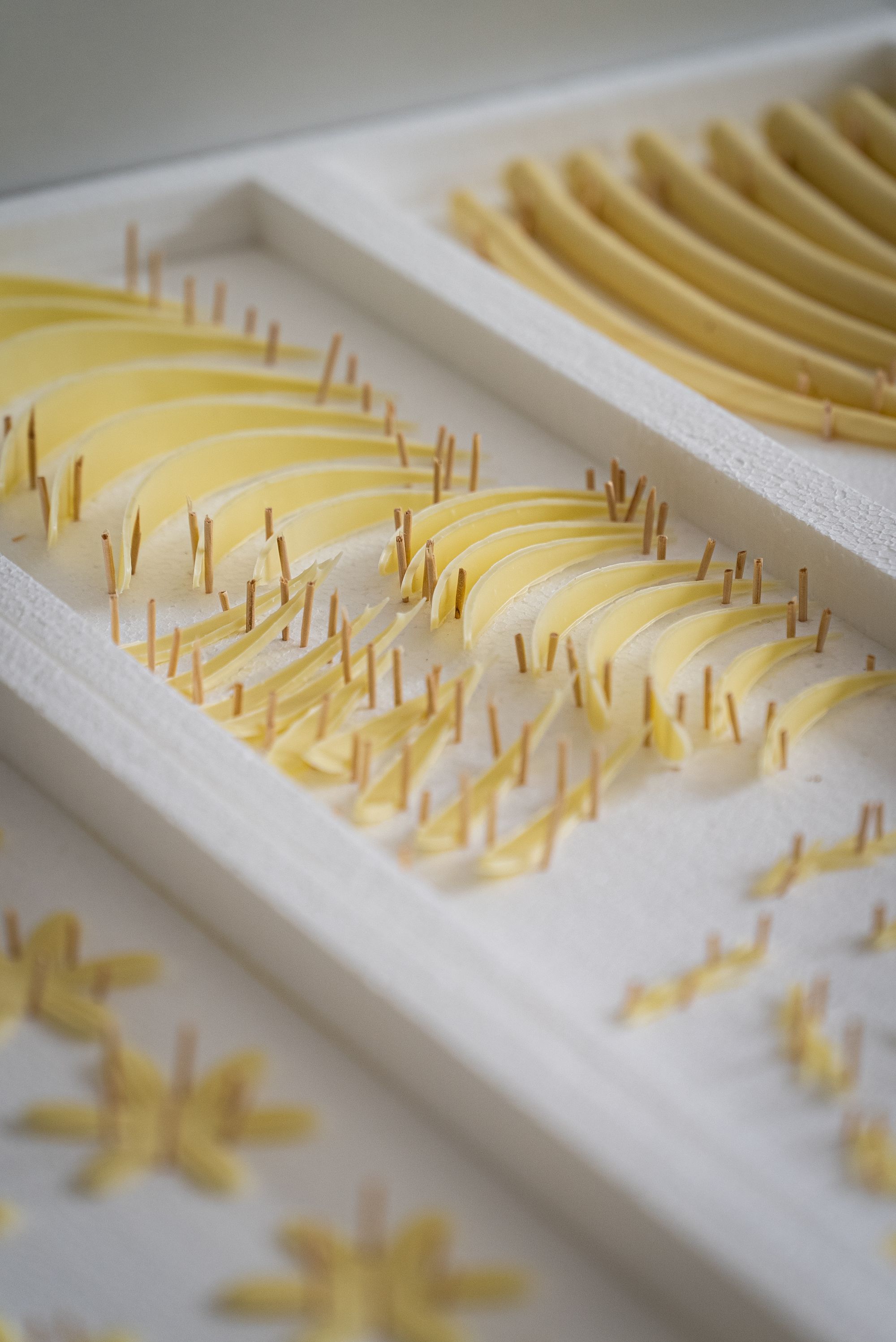

One of these partners was APLI Design, made up of an industrial designer duo Apor Püspöki and Lili Zsabokorszky. These two are both experienced in the world of fine dining, having helped the Hungarian Bocuse d’Or team several times, designing serving utensils and unique molds. Hence the acquaintance and the collaboration has already started during the qualifying rounds, where they explored the shape of the cocoa bean for the creation of a bonbon, a dessert, and street food snacks. In the finals, they also designed the shape of #BONBON and participated in creating the concept of the window display. At #SHARE, they were responsible for the design that was later followed by Mona Lisa, but also for the sponge cake cutter and the template for the decorative chocolate leaves. Perhaps their biggest challenge was #TASTE, where they had to create the basic shapes for the sablé with chamomile milk rice and apple confit, the chocolate ganache, and the tuille petals.

As the maximum size was set for each dessert (in centimeters and weight), the designs had to be modified several times by millimeters and grams. This was the case, for example, with the mold of the dough base created for #TRANSFORM, which combined the shape of Éclair and Macskanyelv (‘Cat’s tongue’—a traditional Hungarian dessert consisting of dough filled with sweet pudding—the Transl.) and where the creams and other toppings provided the excess weight. Of course, in addition to the molds used in the competition, some were also made for practice, so the work was very time- and energy-consuming. Laser cutting, water jet cutting, electroplating, 3D printing, precision casting, silicone mold making, metal and plastic machining, and patterning with silver or silicone—just to name a few. They constantly participated in the tastings, so they received immediate feedback, and it was a great experience to work in a team with excellent professionals in the field of confectionery.

Edina Németh, the founding paper artist of Edina’s paper, has also joined the project. Edina is skilled at using paper novel ways, creating light, yet stable planar and spatial forms. Working with some of the world’s leading fashion brands, it was no question that she would be quick to adapt to the aesthetics dictated by the competition. The project was an exciting one for her, as the creative concept had to be translated into the world of chocolate, while also showcasing Hungary. She and her team took the biggest role in designing the installation template for the window display—Attila and his talented assistant, pastry chef and sculptor Dávid Domonkos, created the elements using her designs prior to the competition.

The challenge was huge, as chocolate behaves differently from paper, and they needed a structure that would be light, yet stable. In the meantime, however, their creative energies got so high that she even contributed a serving tray and decorative elements inspired by Tokaj to the #SHARE box. In every part of the project the rules had to be closely followed, the reason for which the box that was originally designed had to be modified at the last minute. As it turned out, too many of its elements would have risen out of plane, which could have resulted in point deductions. However, the solution gave way to yet another collaboration: one of the paper leaves placed on the lid of the box was scented with a little perfume sample dreamed up by Zsolt Zólyomi.

Although Attila didn’t make it to the podium in the end, these examples clearly show how much knowledge and work was needed just to participate. And let’s not forget about the countless food experts, pastry chefs, chocolate experts, photographers, trainees, and assistants who volunteered their time over the weeks to help prepare for the event—even if anonymously, they also contributed to the success. It has been a challenging and difficult journey, but we can be confident that every event of this kind highlights the complexity of gastronomy and opens new doors to a better future.

Photos: Norbert Ádám Kiss and WCM Official

An imaginary house inspired by the winter wonderland

Gen Z: snowflakes or future revolutionaries?