The history of still life, and in particular of the vanitas genre, goes back several centuries. The symbolic groups of objects displayed in these works expressed the transience and futility of life. The art of Sándor Körei puts this classical genre in a new context: his lyrical works preserve the narrative of withering and the passing of time. We spoke to the Hungarian artist about his contemporary approach to still life, sculpture, and creation. Interview.

Sándor Körei didn’t set out to become a sculptor but wanted to work in graphics or animation. As he knew that he wanted to spend his high school years at the Hang-Szín-Tér Art School in Bodajk, he decided to choose sculpture as a specialization, just to be safe, and finally got accepted there. “I was a little disappointed, but then it was love at first sight from the first week,” Sándor said about the beginning. After high school graduation, he worked in the bronze foundry in Mór, while preparing for his entrance to the Hungarian University of Fine Arts in Budapest, and finally, during his university studies his artistic language began to take shape.

Your artworks are, in fact, sculptural transcriptions of the still-life genre typical of painting. Why did you become more deeply involved in this artistic medium? How did this story begin?

The essence of the visual artist Margit Koller’s course is that students from different year groups always create on a given theme. And one of these courses was titled: ‘Error: entity does not have the right attribute.’ I approached the task by starting to examine each word and its meaning. Then, at some point, I began to look more deeply at still life with a similar method, and how its different attributes relate to the work as a whole. This was also partly the basis of the work I created during the course: essentially a paraphrase of Dezső Czigány’s Still Life with Apples. I placed the objects portrayed in the original work—drapery, plates, apples, and wine bottles—as real objects in the space, according to the original composition. I enclosed these elements in separate glass boxes, tailored to their own geometric dimensions, which also created a kind of floating effect.

Something happened during the exhibition that concluded the course: the glass-encased elements started to deteriorate. You might say that this realization was in fact due to chance. In my subsequent works, I have consciously incorporated the motif of decay, which is also characteristic of vanitas, a sub-genre of still life, thus creating a new situation for my further sculptures.

In your series Flowers with Vase, the plant elements are seen floating above the vases, again one by one, enclosed behind glass. What is the underlying philosophy behind this gesture?

My works always have a system of their own—that’s probably also how I operate: I have an analytical state that leaves its mark on my artworks. Then, in the end, it is important that the individual elements form a harmonious whole.

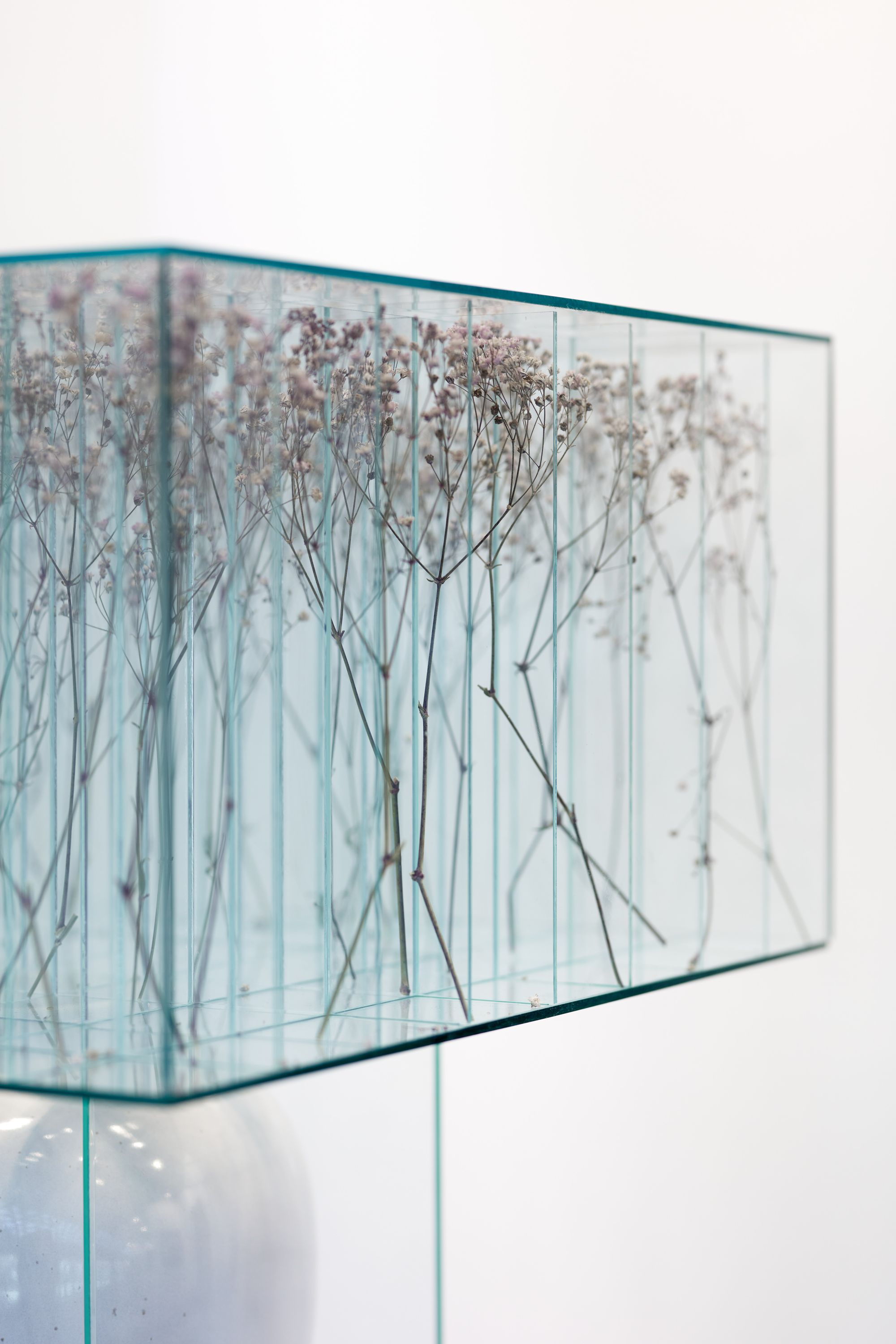

Lately, I’ve often come across the question of why I don’t use plexiglass instead, because of how fragile or heavy glass is. However, besides the qualitative differences between the two materials, glass also carries a new layer of meaning. I think that when you put an object behind glass, it immediately becomes more important—just think of museums or display cases at home. So by having the ‘story’ of my work behind glass, the viewer becomes an observer who cannot influence what is happening inside. This creates a sense of incompleteness, a lack of control. This was my aim, to show evanescence as stripped down as possible. However, there is also a double dramatic quality to it, as the plants gradually wither and transform, but the harmony of the composition itself remains.

More recently, I have been experimenting with acid-etched glass boxes. The opaque surface causes irregular shapes to appear in front of the viewer: a flower or a leaf meets the glass, but it is not possible to fully capture what is happening behind the glass. In these sculptures, I create plants that do not actually exist, and give them fictitious taxonomic names.

Does it have a significance as to which plants and which vases you choose to combine in your sculptures?

The system of symbols based on the flower motif has a great deal of history and past, but in my work, their selection and arrangement are more part of an intuitive process.

I initially sourced the vases I used from flea markets, antique shops, and online, but I feel I have exhausted these possibilities. At the moment, for example, I am interested in the Karcag veil glass (fátyolüveg) vases, which were made in the 1960s and were given a special crackled surface by a special process. And for one of my latest works, I am working with a potter from Mór.

Your creative process is characterized by a spirit of experimentation: you have replaced the everyday objects you used at first with plant compositions, then enclosed variations of these, first behind transparent and then acid-etched glass containers. In addition to your sculptures, you have also created works in which you return spatial compositions to the pictorial plane.

I think experimentation as a whole is typical of my creative attitude. I like to experiment not only with a particular subject, but also with different techniques, such as cyanotype, or in the case of my photographs, the use of long shutter speeds. In my photographs, the floral arrangements are created by manipulating the depth of field affecting each element: here I was interested in how I can condense a series of events into a single image. In fact, these works are a detail of what I am representing in my sculptures.

You are a represented artist at the Molnár Ani Gallery in Budapest, and most recently we were able to see your work at the Art and Antique art fair. To what extent does the ephemeral nature of your artwork influence the decisions of art collectors and buyers?

We have been working with Molnár Ani Gallery for more than a year, which has given me the opportunity to exhibit at several fairs in Hungary, as well as at ARCOmadrid in February this year. I have noticed a growing interest in my work, with prestigious national and international collectors from England, Spain, and Norway buying pieces. I try to listen to the different reactions—many are captivated by the lyrical, airy nature of the sculptures. Something else that might be interesting about my work is that although it departs from the classical direction of sculpture, it is still rooted in classical fine art. Today, however, I prefer to work with dried plants, which creates a more controlled situation but still retains the original concept.

What adds another exciting layer to the work is that the glass itself actually transforms over time: it is a moving material whose structure is a transition between solid and liquid.

As an emerging artist, do you feel like you have found yourself in this genre of artistic expression?

I don’t see my long-term goals yet, but I feel that I have plenty to explore within this theme: new paths are constantly opening up. Thanks to Ani Molnár Gallery, I will have the opportunity to present my works again in April at the Art Brussels international art fair. And in May I will be able to test how my sculptures function in the open space at the Káli Art Park. My exhibited work Columella Illunium, made for this site, will be larger in scale than the previous ones, and here too, using acid-etched glass, the opaque surface will abstract the work into forms with blurred outlines. I was also motivated by the intention to show how this glass surface reacts to sunlight: it makes the whole work seem to come to life.

Sándor Körei | Instagram

Homeliness among concrete pillars | Plus One Architects

Like a culinary exhibition