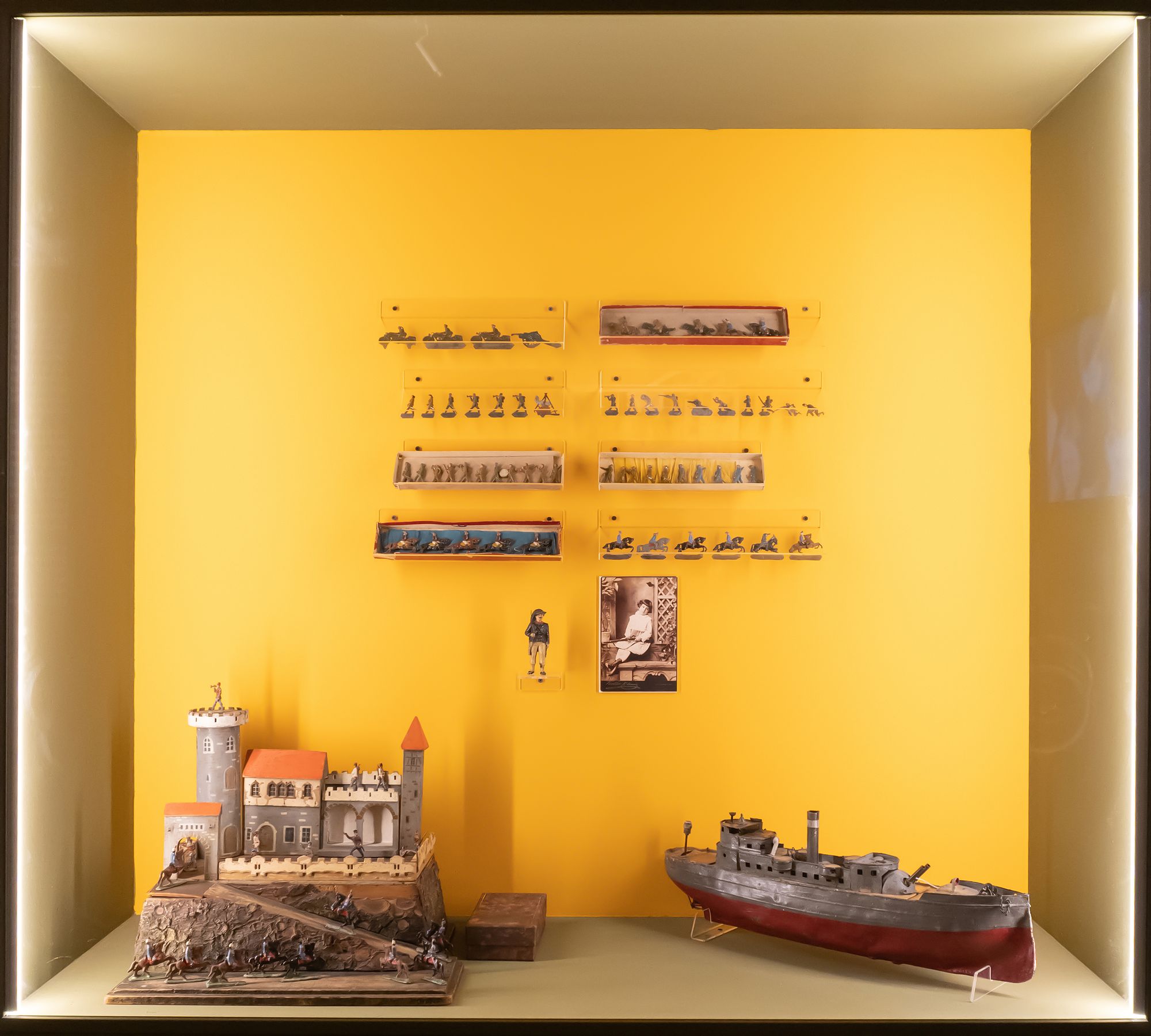

The Budapest History Museum—Castle Museum’s new exhibition, Kádár (játék)katonái (meaning Kádár’s [Toy] Soldiers), presents the world of injection-molded plastic figures of the twentieth century and their socio-political aspects. Why were the toy soldiers from Hungary special within the Eastern Bloc? Which countries’ figures made it across the Iron Curtain? What was the American toy factory Marx doing in the Soviet Union? How did Star Wars influence the toys? The exhibition features figures of mythological heroes, Indians, cowboys, and soldiers—focusing mainly on the latter, we asked curator and historian János B. Szabó, about the exhibition.

Did you have toy soldiers as a child?

Of course. I was a kid in the 1970s, I used to buy the same figures you see in the exhibition for one or two Forints each, and the gunners for five Forints.

Where were these figures made?

Most of these figures were made by self-employed craftsmen living and working in Budapest. One of the surprising things that came to light at the exhibition was that there have always been these privately working artisans, even already in the 1950s. And after 1956 they started making plastic soldiers.

How did the concept of the Hungarian toy soldiers evolve?

When I was a kid, the Vietnam War had barely ended and I was convinced that my soldiers in the funny hats were Vietnamese. Now it turned out that such figures were only made in one place outside Hungary, and that was Australia. So these were replicas of Australian soldiers from World War II. All this shows that the source of the toy selection in this country from the 1960s onwards was the emigration of ’56. What was made here in Hungary had its roots in countries where there were Hungarian communities who kept in touch with relatives back home and sent home gifts, or later, when travel became possible again, they brought them home themselves. This is made obvious by the prevalence of American toys: other Central European countries copied Western toys as well—like those from West Germany, France, Italy—but American toys were almost exclusively copied in Hungary. What is also telling, is that these toys were among the cheapest in the US.

How much state control was there over the production of the figures?

The craftsmen were supervised by the councils, which gave them the trade licenses. The council, however, is a lower level of government; there seems to have been little direct state intervention. At the same time, initially the self-employed were not rich, only family members could work for them and the machines used for injection molding were also quite expensive. So they had quite a uniqe way of product development, collecting samples that could be copied. Since lead was banned as a toxic substance in the 1960s, these types of plastic soldiers became the sole dominant product in the country. But what is even more interesting is that, after collecting all different types of toys, was to learn that Hungarian children—for the reasons mentioned above—had been playing with NATO soldiers, not soldiers of the Eastern Bloc, ever since the late sixties.

In addition to the classic green version, the soldiers and tanks also come in red, yellow, and even mixed colors. Why is that?

In the exhibition, we attempted to frame the green ones as the original American, French, etc. figures. In Hungary, however, this type of toy was indeed produced in all colors of the rainbow. So they were not very military-looking. This was also due to the problems of the craftsmen: when plastic production started, pure chemical combinations were not yet available, and the imported material was distributed according to a certain order, so the cooperatives had the leftovers of the leftovers. At the same time, the level of waste processing was much more advanced than one might think. There was a lot less plastic than today, but it was collected, recycled, and added to the raw material at the factory. The product was good quality plastics, but it also meant that they couldn’t control the colors, so they molded from whatever they had access to.

What was the situation in other Eastern Bloc countries?

Outside Hungary, everyone modeled their own army, everywhere else defense education was a central issue. These toys were—even before—essentially means of ideological education and patriotism because children would eventually become soldiers. East Germans, for example, as a way to honor traditions, kept in line with earlier models in terms of uniforms and equipment, such as the helmet developed for the Wehrmacht. Czechoslovakia also followed traditions, using an earlier, non-plastic-based technology invented in Austria at the beginning of the century. Their factory in Moravia operated until the mid-1980s. The only place similar to Hungary was Romania, where the injection-molded figures were also made after Western models, but the raw materials and manufacturing were even worse.

And what was the case in the Soviet Union, then a world power?

In the Soviet Union, to solve supply issues, in the case of several products the state made deals with large foreign companies, which would then build an entire factory. This was also the case for toy soldiers. In what is part of Ukraine today, a toy factory was set up with a British subsidiary of the American company Louis Marx & Co., and the Soviets bought the licenses for figures of vikings, characters from the wild west, and Soviet soldiers from the Second World War. Thus, the best quality Soviet figurines were designed by the American Marx company, based on patterns by American designers.

No enemy army or soldiers were produced?

Traditionally, toy soldiers had no enemies. In Germany, where this genre enjoys a very rich culture, they have also made enemies. Between the two world wars, they produced the most toy soldiers—three million a year. In fact, the British and French soldiers were sold in Britain and France, but soldiers from practically every major state’s army were produced, including the figures of the Royal Hungarian Army. For a long time after World War II, everyone only produced figures of their own army. It the United States who first made a set in 1964 which also included German soldiers, and Japanese were also added later. By the 1970s, the British had produced the Wehrmacht’s entire military arsenal, but surprisingly, you could also buy the tanks of the former German army in West Germany. So in essence this was a sort of retrospective trend, through which you could reenact the World War.

What is the situation today? How much demand is there for these types of plastic soldiers today?

These little green soldiers are still manufactured in China today and are in stock. What the American company Marx invented in the 1950s is what has been simplified there. A copy of the American model was good for foreign markets, and Chinese children didn’t play with these types. In any case, product line is completely obsolete today, and the toy market saw a major paradime shift in the 1970s and 1980s.

What could have been the reason for this?

On the one hand, technical solutions have improved, and higher-quality, but still cheap, mass-produced figures have hit the market. On the other hand, there were also changes in mentality. The US, for example, was fed up by then with the Vietnam War, and then came Star Wars, which said a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away... It simplified a lot of things: it’s a nuisance to produce the national army everywhere, and the enemy especially, not to mention that yesterday’s enemy is a friend today, or vice versa. But with this, there is no need to change anything, you can sell the same pieces everywhere and there are no conflicts between nations either. In fact, it was Star Wars that turned this new type of toy, the action figure, into the last man standing. Then in the 1980s came G.I. Joe, which was an American soldier, but who was fighting a fictitious terrorist organization, and what’s more, by 1983 the Soviets became its allies. So there was no less violence and war in the children’s world, but it was removed from reality.

Kádár’s Toy (Soldiers)

Budapest History Museum—Castle Museum

Open until 15 March 2023

Curator: János B. Szabó PhD, historian, museologist | Assistant curator: Álmos Molnár, collection manager, museologist

Exhibition photos: Balázs Medve/BHM

Portrait photo: Olivér Kovács

A matchbox full of past

The flora of Krajna lives on in KRAYNA’s latest cosmetics